| Type | Feature/Attribute | Levels |

|---|---|---|

| H1a | Financial transparency | (1) Doesn't engage in transparency; (2) Engages in transparency |

| H1b | Accountability | (1) Doesn't engage in accountability; (2) Engages in accountability |

| H2 | Relationship with host government | (1) Friendly relationship with government; (2) Criticized by government; (3) Under government crackdown |

| Comparison | Organization | (1) Amnesty International; (2) Greenpeace; (3) Oxfam; (4) Red Cross |

| Comparison | Issue area | (1) Emergency response; (2) Environment; (3) Human rights; (4) Refugee relief |

| Comparison | Funding source | (1) Funded primarily by many small private donations; (2) Funded primarily by a handful of wealthy private donors; (3) Funded primarily by government grants |

Navigating Hostility: The Effect of Nonprofit Transparency and Accountability on Donor Preferences in the Face of Shrinking Civic Space

Governments across the world have increasingly used laws to restrict the work of nonprofits, which has led to a reduction in public or official foreign aid directed towards these groups. Many international nonprofits, in response, have turned to individual donors to offset the loss of traditional funding. What are individual donors’ preferences regarding donating to legally besieged nonprofits abroad? We conducted a conjoint experiment on a nationally representative sample of likely donors in the US and found that learning about host government criticism and legal restrictions on nonprofits decreases individuals’ preferences to donate to them. However, organizational features such as financial transparency and accountability can protect against this dampening effect. Our results have important implications both for understanding private international philanthropy and how nonprofits can better frame their fundraising appeals at a time when they are facing restrictive civic spaces and hostile governments abroad.

philanthropy, conjoint experiments, donor heuristics, repression, NGOs, civil society, nonprofits

What determines individual donor behavior?

A large body of work in philanthropy explores the factors that shape private donor motivation, including altruism, reputational benefits, and alignment with personal values (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Wiepking, 2010). However, this research has overwhelmingly looked at individual donor behavior and motivation for giving to domestic organizations instead of international causes (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Tremblay-Boire & Prakash, 2017). Giving to local organizations involves more observable results, while the benefits of donating to organizations working abroad are less visible and more removed from donors (Casale & Baumann, 2015). Tremblay-Boire & Prakash (2017) confirm this, finding that “donors are more likely to donate to a charity operating locally than to a charity providing identical service abroad” (2017, p. 644).

This difference in donor preferences for giving to international NGOs has been understudied because conventionally, states and foundations have been among the main funders of INGOs. The third wave of democratization and the collapse of the Soviet Union led donor states to channel substantial resources through NGOs, often in response to donor fears that recipient states would use aid inefficiently (Dietrich, 2013). Institutional donors and private foundations perceived NGOs as more efficient, more nimble, less bureaucratic, and more trustworthy than states that face poor governance and weak political institutions.

But as INGOs gained more power in global policy circles, they faced a number of criticisms. Many organizations struggle to balance efficient large-scale operations with the grassroots connections and consensus-building that drove their early success (Jalali, 2008; Mitchell et al., 2020). As a result, many INGOs worked to establish and enhance their accountability, responsiveness, and legitimacy (Edwards & Hulme, 1996; Gourevitch & Lake, 2012). These actions were a result of many organization-level factors that can potentially impact nonprofit efficacy, including organizational and governance structure, leadership, strategy, transparency, and accountability. Organizational and governance structures define how decisions are made and who participates in decision making. While some nonprofits follow more democratic governance models—such as expanded membership to Global South countries and devolving more decision-making powers to the regional or country levels, others have a more centralized structure (Mitchell et al., 2020, p. 155; Wong, 2012). Leadership can be defined as how leaders “handle the external and internal politics of making their organizations more effective and responsive,” and what sort of organizational cultures they create (Mitchell et al., 2020, p. 178). Finally, strategy involves whether the organization has a long-term strategic plan that emphasizes sustainability, innovation, learning, and adaptation (Mitchell et al., 2020, p. 100).

However, organizational structure, leadership, and strategy (among other organization-level factors) are often not visible to the average individual donor. We therefore focus on two organization-level factors that are most visible to the average donor—financial transparency and accountability. Assessing an NGO’s deservingness and efficiency demands substantial time and resources, which individual donors typically lack (Croson & Shang, 2011; Tremblay-Boire & Prakash, 2017). As such, donors rely on cues and heuristics when deciding to support an NGO. Compared to other organization-level factors, news about financial mismanagement and lack of transparency and accountability may be more easily available. Many nonprofit scandals involve some form of financial wrongdoing (Prakash & Gugerty, 2010). Notable examples include the United Nations’ Oil-for-Food program, aimed at alleviated Iraq’s sanctions-induced hardships in the 1990s, which was marred by revelations of widespred financial fraud, limited food distribution, and lack of accountability in 2004. Numerous other cases Gibelman & Gelman (2004) demonstrate how financial mismanagement, embezzlement, fraud, and lack of accountability can decrease public trust and reduce donations to nonprofits. Globally, around 5% of revenue is lost annually due to fraud (Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, 2021). Misappropriation of assets and embezzlement schemes are among the most common forms of financial fraud (Lamothe et al., 2023). To save time and present easily accessible information, watchdogs such as Charity Navigator often rate charities on financial and accountability metrics and present this information in a quick, user-friendly format.

Thus, in this paper, we explore the effects of two possible categories of heuristic frames that can impact individual-level giving: (1) organization-level heuristics, reflected in practices of transparency and accountability, and (2) structural heuristics, particularly an NGO’s relationship with its host country. We hypothesize that each type plays a role in shaping individual preferences for engaging in philanthropy.

Organizational heuristics: NGO practices

We first examine the impact of two organizational practices—financial transparency and accountability—on individual donor preferences. Financial transparency, or the “degree of completeness of information provided by [organizations] to the [public] concerning [their] activities,” (Vaccaro & Madsen, 2006, p. 146) is one tangible heuristic that donors turn to when making decisions. Transparency can involve proactive sharing of information with stakeholders, participation in data transparency platforms, avoiding financial misconduct, and exhibiting trustworthiness. NGOs can engage in financial transparency in a variety of ways, such as distribution of audited financial statements and voluntarily sharing information with third party intermediaries. Research shows that transparency is associated with greater donations, lower debt, and better governance (Harris et al., 2023; Harris & Neely, 2021; Saxton et al., 2012). It can also enhance donor trust and confidence in organizations (Vaccaro & Madsen, 2006).

Previous research has found that media exposés about charity mismanagement can generate negative reputational spillovers for the charitable sector (Gibelman & Gelman, 2004). Diversions—or the unauthorized use of an organization’s assets, including embezzlement and theft—can result in a decrease in donations. This effect becomes even stronger with media coverage of diversion (Harris et al., 2023). Organizational financial transparency can reduce actual or perceived information asymmetries between donors and charities, thus potentially increasing an individual’s likelihood of donating to an INGO.

Accountability also influences donor preferences. Accountability is the willingness of the organization to explain its action to shareholders (Charity Navigator, 2020) and build and manage relationships with stakeholders or client populations and donor groups. It also reflects how well an organization’s mission is aligned with its resources (Sloan, 2009). As NGOs gain more prominence, stakeholders seek assurance that their donations will make a real difference—effective accountability can encourage NGOs to become more closely aligned with community practices and help expand stakeholder support (Murtaza, 2012). Problems with accountability usually occur when organizations ignore their stakeholders’ preferences and use judgements or actions which may not align with one or more of their constituent groups (McCambridge, 2019). The absence of accountability is associated with decreased public trust, deteriorated reputation, and lower perceived quality (Becker, 2018).

Though individual donors would like to have some assurance that their resources will be used appropriately and organizations are not spending too much on overhead (Hung et al., 2023), individuals interested in supporting charities cannot thoroughly vet every aspect of the organization (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021; Tremblay-Boire & Prakash, 2017). To more easily judge financial transparency and accountability, donors may use ratings by watchdog organizations like Charity Navigator and GuideStar as heuristics to guide their decisions.2 Research shows that initiatives to address information gaps by these organizations can substantially increase donations (Gordon et al., 2009; Sloan, 2009; Tremblay-Boire & Prakash, 2017). We expect that donors will respond to signals that organizations engage in transparency and accountability practices:

H1a: If NGOs are financially transparent, then individual private donors will have a higher likelihood of supporting or donating to them.

H1b: If NGOs are accountable, then individual private donors will have a higher likelihood of supporting or donating to them.

Structural heuristics: Host country conditions

While NGOs have control over organizational factors such as transparency and accountability and can work to improve these characteristics and public perception of them, NGOs may have little to no control over structural factors that can also influence philanthropy. These structural factors include political contexts in NGO host countries, especially a restrictive environment for civil society organizations. A global cascade of anti-NGO laws in recent decades has created barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy for civic organizations (Bakke et al., 2020; Chaudhry, 2022; K. Dupuy et al., 2016; Glasius et al., 2020; Heiss, 2017). The use of such anti-NGO laws, also referred to as administrative crackdown (Chaudhry, 2022), is different from regulations that simply set standards for appropriate organizational behavior and set penalties for violations (North, 1990).3 However, the anti-NGO laws discussed in this paper, such as the Russian Foreign Agent law, are not grounded in international legal principles and do not give nonprofits the freedom of association or access to resources (Robinson, 2024). As a result, NGOs must spend more time, effort, and resources to ensure their survival—at the expense of pursuing their missions.

Some NGOs have adapted to these legal crackdowns by recreating their organizations and changing their mission to avoid directly confronting the government. Research on anti-NGO laws in Bangladesh and Zambia shows that NGOs with broad missions shifted from advocacy to service work, while those focused mainly on transnational advocacy altered their targets, issues, and language (Fransen et al., 2021). Similarly, in Russia, many NGOs working with foreign partners and lobbying the central government no longer consider it an effective strategy (Sundstrom et al., 2022). Overall, fewer organizations work on contentious causes, instead focusing on safer issues like health and education. These changes in the civil society legal environment have influenced official donor responses. While multilateral donors do not reduce aid in response to anti-NGO laws, these laws are associated with a 32% decline in bilateral aid inflows (K. Dupuy & Prakash, 2018). Further, advocacy-oriented donors—i.e., those that fund democracy and civil society promotion activities—reduced their spending by 74%, but did not cut their spending on development projects such as education, health, water, and sanitation (Right et al., 2022).

However, previous literature has established that individual private donors do not make the same considerations as official donors when deciding to donate (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021; Desai & Kharas, 2018). Private foreign aid does not have to deal with the same strategic and political considerations as official aid and therefore, may be in a better position to respond to recipients’ needs on the ground (Easterly & Williamson, 2011). When a potential recipient NGO faces legal crackdown in its host country, private individual donors can respond by (1) increasing their donations as a sign of support and solidarity, (2) decreasing their donations, punishing the NGO for perhaps doing something to run afoul of its host government, or (3) not considering the host country legal environment and making no change in their donation behavior. Chaudhry & Heiss (2021) find conflicting donor responses to foreign restrictions—while some prospective donors punish nonprofits for doing something “wrong” to incur host government restrictions, most tended to increase their support, stating that restricted NGOs are “doing good work in countries where it is tough for groups like them to operate and they need all the help they can get” (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021, p. 496). Chaudhry et al. (2021) explore how different combinations of donor characteristics determine which response individuals are likely to take when NGOs face crackdown. They find that donors with longer experiences with the nonprofit sector and high levels of social trust—i.e., those who frequently volunteer, regularly donate to charity, and trust political institutions—are more likely to maintain their support for international NGOs that face criticism or crackdown abroad. Thus, anti-NGO laws may act as a heuristic to individuals donors that NGOs undertake crucial work abroad, which is why governments perceive them as threatening and seek to restrict their work.

This is especially true for nonprofits that rely more heavily on private funds, rather than government funds. Previous research finds that, “individual donors thus seem to be more willing to support besieged human rights organizations when they are unencumbered by government funds” (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021, p. 496). Similar trends can be seen even after nonprofits face restrictive political and civic environments in other specific issue areas. For instance, in 2022, after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, private philanthropy towards abortion funds skyrocketed (PBS News, 2022)—a significant development as abortion funds rely largely on individual donors (Cohen, 2022). Therefore, we expect that anti-NGO restrictions imposed by host-country governments are likely to boost individual donors’ inclination to donate to affected organizations.

H2: If NGOs face legal restrictions abroad, then individual private donors will have a higher likelihood of supporting or donating to them.

Examining the joint impact of organizational and structural factors

Identifying the causal link between structural factors and donor behavior is more difficult than measuring the link between organizational factors and donor behavior because (1) NGOs have less direct control over their political environments, and (2) organizational characteristics like financial transparency and accountability can sour the NGO-government relationship—governments may be more likely to target NGOs that lack financial transparency and accountability. Moreover, states pass anti-civil society laws in response to broader political trends within their borders, and they regulate NGOs strategically to maximize the benefits and minimize the costs of working with international NGOs (Heiss, 2017). States are more likely to restrict NGOs when organizations pose a threat to regime stability or preferences—for instance, when INGO issue areas threaten government policies, or when INGOs receive substantial foreign funding (K. E. Dupuy et al., 2015).

Donors show increased willingness to donate to NGOs facing government restrictions/criticism while being financially transparent and accountable. While concerns about NGO mismanagement and lack of financial transparency may signal concerns about an NGO’s operations and its ability to abide by the host country’s regulatory environment, the presence of such transparency and accountability may instead convince donors that government targeting of NGOs may be ill-intentioned rather than simply a manifestation of financial oversight. Donors may view anti-NGO laws and inhospitable civic environments as a sign of governments looking to restrict groups that seek to keep governments accountable, rather than merely auditing and punishing groups that violate routine regulations.

Therefore, both states and individual donors expand and contract their regulatory environments (for states) and support (for donors) for NGOs in response to the interplay between domestic politics and organizational characteristics. The same NGO feature that can increase the likelihood of government restriction can also simultaneously serve as a donor heuristic and influence perceptions of NGO deservingness. Based on the importance of transparency and accountability for donors in general, we expect that legal restriction will interact with these practices and shape donor preferences:

H3: If NGOs face legal restrictions abroad and are financially transparent, then individual private donors will have a higher likelihood of supporting or donating to them.

Research design

It is possible to study the effects of both organizational and structural heuristics on donor preferences individually, but disentangling the interaction of these heuristics adds complex dimensionality and makes more standard experimental work costly and statistically fraught. To address this, we use a conjoint experiment to measure the causal effect of both organizational and structural heuristics on individuals’ preferences for donating to international NGOs. (Hainmueller et al., 2014). Conjoint experiments are increasingly common in nonprofit studies, particularly for studying individual donor behavior (Bachke et al., 2014; Hirschmann et al., 2022; Silvia et al., 2023).

A conjoint research design also allows us to estimate treatment effects even if respondents do not see every combination of organization attributes, and correspondingly provides a substantial increase in statistical power. In standard factorial experimental designs, participants would ordinarily need to be shown all possible combinations of experimental attributes. In our experiment, we presented respondents with six possible treatments with randomized attributes for each treatment, yielding 576 possible unique combinations of features. Even with respondents answering twelve iterations of the experiment, not every combination was seen. However, as long as all the possible organizational attributes are well randomized and there are no systematic biases toward specific options (i.e., more respondents select the first option because it is the first) or toward earlier iterations of attribute choices (i.e., respondents are more careful and attentive for the first hypothetical organization than the last), we can pool all observations together for specific attributes of interest while marginalizing across all other attributes (Kertzer et al., 2021). This allows us to (1) estimate the effect of each experimental treatment even if some unique combinations of attributes were unseen, and (2) use a much smaller sample size than would be required in a more traditional factorial design.

While the ability to select key attributes and marginalize over others provides us with analytic flexibility, it also raises possible issues with multiple comparisons, p-hacking, and selective cherry-picking (Bansak et al., 2021), especially given the fact that we have 576 possible combinations of independent variables to explore. As such, before launching the survey experiment, we preregistered a subset of confirmatory and exploratory hypotheses at the Open Science Framework.4 These hypotheses deal specifically with our key research questions about the effect of transparency, accountability, and crackdown on the propensity to donate, along with comparison treatment effects for organization brand name, issue area, and funding sources. We also examine the interaction between transparency, accountability, and host-country relationships.

Sample

We fielded our survey experiment through Centiment, which recruits representative samples of paid (and highly engaged) survey participants online. To see how varying NGO characteristics influence the decision to donate, our sample was representative of the population of people who are likely to donate to charity. We asked potential participants a screening question about their philanthropic behavior early in the survey—if a participant responded that they give once every few years or never, they were disqualified from the study. We also included an attention check question early in the survey and removed respondents who failed the question. Importantly, these screening questions were presented prior to the experimental manipulation to avoid post-treatment bias (Montgomery et al., 2018). Following screening, we received 1,016 viable responses. Tables A1, A2, and A3 provide a detailed breakdown of the individual characteristics of our sample. In general, respondents were well balanced across all pre-treatment characteristics, including gender, age, education, income, and attitudes toward charity. Additionally, Table A4 compares sample characteristics with nationally representative estimates from the 2019 Current Population Survey (CPS). Our sample matches national proportions of age, marital status, and education, and contains slightly more men and slightly higher income levels than the general population. Due to the initial screening question that limited participants to those with an interest in charitable activity, respondents are far more likely to have donated, volunteered, or voted in the past year than population CPS estimates. Our reported causal effects are therefore not representative of the entire population and instead are generalizable to people interested in charitable giving.

Experimental design

After collecting baseline information on respondent demographics and attitudes toward charity and voluntarism, we showed participants a set of randomly shuffled hypothetical international NGOs described with randomly shuffled features or attributes. In this paper, we hypothesize and empirically test the effect of financial transparency, accountability, and host country relationship on the likelihood of donations. In our experiment, we included a few additional treatments to aid with the interpretation and comparison of effect sizes for our treatments of interest. In total, we varied six different organizational and structural attributes that might have an effect on donor behavior: (1) organization name and branding, (2) organization issue area, (3) financial transparency practices, (4) accountability practices, (5) funding sources, and (6) relationship with host government (see Table 1).

At the time of designing the study, Charity Navigator—a large database of US nonprofit financial information—categorized international nonprofit activities into four general causes: (1) humanitarian relief supplies, (2) international peace, security, and affairs, (3) development and relief services, and (4) environment. Accordingly, we used four nonprofits that are stereotypical for each cause: the International Committee of the Red Cross (humanitarian relief), Amnesty International (human rights), Oxfam (development), and Greenpeace (environment).5 We also varied several other features, including four issue areas (emergency response, environmental advocacy, human rights advocacy, and refugee relief), two organizational practices (financial transparency and third-party accountability audits), three funding sources (many small private donations, a handful of wealthy private donors, and government grants), and three relationships with host governments (friendly, criticized by the government, and under government crackdown).

After presenting respondents with a set of three randomly generated organizations, we asked them which of the three they would be willing to donate to, along with an option for no selection (see Table 2 for an example). This choice indicated donation intention and reflected the option the respondent preferred most within that set. We then repeated the process eleven more times for a total of twelve randomized iterations of hypothetical combinations of attributes, resulting in 12,192 completed experimental tasks (12 iterations × 1,016 respondents). This iterative process across twelve experimental tasks is typical of conjoint analysis and allows us to estimate individual-level differences using a multilevel model and determine both aggregate respondent preferences and the causal effect of each experimental feature on those preferences.

| Attribute | Option 1 | Option 2 | Option 3 | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | Greenpeace | Oxfam | Red Cross | — |

| Issue area | Environment | Refugee relief | Refugee relief | — |

| Transparency | Engages in transparency | Doesn't engage in transparency | Doesn't engage in transparency | — |

| Accountability | Engages in accountability | Engages in accountability | Engages in accountability | — |

| Funding sources | Funded primarily by a handful of wealthy private donors | Funded primarily by government grants | Funded primarily by a handful of wealthy private donors | — |

| Relationship with host government | Under government crackdown | Criticized by government | Criticized by government | — |

Modeling and estimands

We analyze the results using a multilevel Bayesian multinomial model (see the appendix for complete model details). Our experimental data has a natural hierarchical structure, with 3 questions nested inside 12 separate experimental tasks, nested inside each of the 1,016 respondents, which lends itself to multilevel modeling (Jensen et al., 2021). Since it was impossible for every respondent to see every possible combination of all 12,000+ experimental tasks, multilevel modeling allows us to pool together information about respondents with similar characteristics facing similar sets of choices. Moreover, using random respondent effects provides natural regularization and shrinkage for our estimates—experimental tasks that happened to appear more often due to chance will be accounted for and their frequency will not bias the overall causal effect. We define our model and priors in Equation 1.

\[ \begin{aligned} &\ \mathrlap{\textbf{Multinomial probability of selection of choice}_i \textbf{ in respondent}_j} \\ \text{Choice}_{i_j} \sim&\ \mathrlap{\operatorname{Categorical}(\{\mu_{1,i_j}, \mu_{2,i_j}, \mu_{3,i_j}\})} \\[10pt] &\ \mathrlap{\textbf{Model for probability of each option}} \\ \{\mu_{1,i_j}, \mu_{2,i_j}, \mu_{3,i_j}\} =&\ \mathrlap{\begin{aligned}[t] & (\beta_0 + b_{0_j}) + \beta_{1, 2, 3} \text{Organization}_{i_j} + \beta_{4, 5, 6} \text{Issue area}_{i_j} + \\ &\ \beta_7 \text{Transparency}_{i_j} + \beta_8 \text{Accountability}_{i_j} + \\ &\ \beta_{9, 10} \text{Funding source}_{i_j} + \beta_{11, 12} \text{Government relationship}_{i_j} \end{aligned}}\\[5pt] b_{0_j} \sim&\ \mathcal{N}(0, \sigma_0) && \text{Respondent-specific offsets from global probability}\\[10pt] &\ \textbf{Priors} \\ \beta_{0 \dots 12} \sim&\ \mathcal{N} (0, 3) && \text{Prior for choice-level intercept and coefficients} \\ \sigma_0 \sim&\ \operatorname{Exponential}(1) && \text{Prior for between-respondent variability} \end{aligned} \tag{1}\]

We do not include any respondent-level covariates beyond the treatment variables. Because this is an experimental design, any statistical confounding is accounted for during the process of randomization and covariates should have no systematic effect on treatment effects. We do not work with the raw results of the multinomial model directly. Given the conjoint design, we instead create a complete balanced grid of all 576 combinations of feature levels (2 transparency × 2 accountability × 3 government relationships × 4 organizations × 4 issues × 3 funding) and use the model to calculate predicted probabilities of choice selection for each combination of possible treatment values. We then collapse this set of predicted probabilities into estimated marginal means (EMMs) for specific features of interest while marginalizing or averaging over all other predicted variables (Arel-Bundock et al., 2024; Leeper et al., 2020). This marginalization process allows us to isolate the statistical effect of each feature in isolation. We include a complete table of model results in Table A5, along with a brief illustration of converting from regression coefficients to estimated marginal means.

We report the causal effect of each manipulated feature using the average marginal component effect (AMCE), which is equivalent to the difference in estimated marginal means for specific feature levels. For example, when estimating the marginal means of the transparency treatment, we find the average predicted probability across the 288 rows of the reference grid where transparency is true and across the 288 rows where transparency is false, holding all other experimental features and individual covariates constant—the difference between these two estimated marginal means is the AMCE, or the causal effect of the treatment on the probability scale.

Results

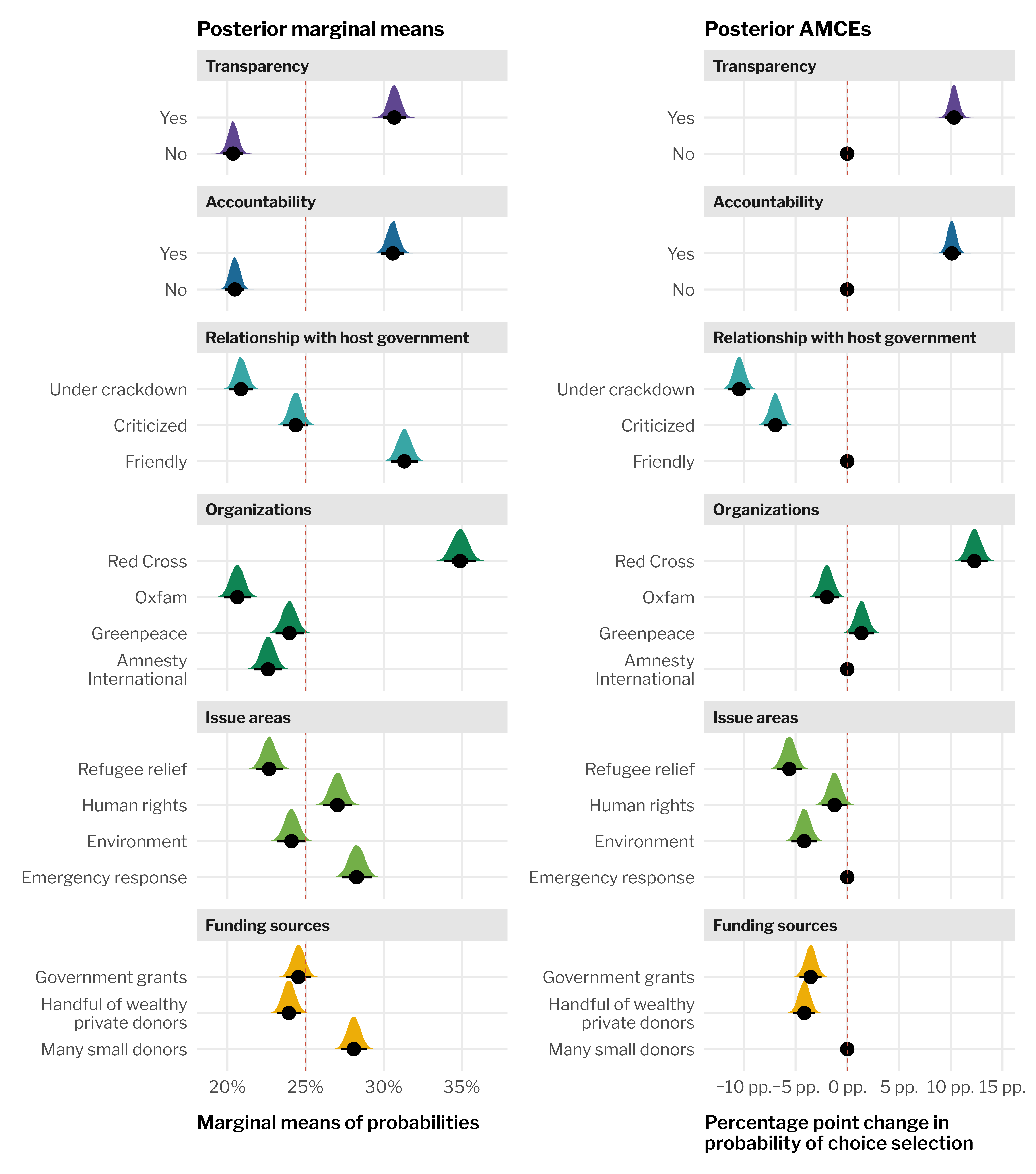

We present the posterior distributions of the marginal means and AMCEs for each of our experimental conditions in Figure 1 and provide posterior medians, credible intervals, and other model diagnostics in Tables A7 and A9. Because AMCEs are relative statements (i.e., contrasts between one feature level and a reference level), we try to use logical reference levels: for binary treatments like transparency and accountability, we calculate the difference between false and true levels; for ordered treatments like host country relationship, we calculate the differences between different levels of crackdown compared to no crackdown. To avoid imposing an artificial order on other unordered treatment variables, we report both marginal means and AMCEs (Leeper et al., 2020).

We provide visualizations of the full posterior distributions of each of the effects of interest, and we report two distributional summary statistics: (1) the posterior median, (2) credible intervals based on a 95% equal-tailed quantile interval. However, we are generally less concerned with the exact point estimates of our causal effects and instead focus on the direction and relative magnitude of their posterior distributions. For inference, we calculate the probability of direction (\(p_d\)), which indicates the proportion of the posterior AMCE that shares the sign of the median and the probability that AMCE is strictly positive or negative.

Effect of comparison treatments

To contextualize the magnitude of the causal effects for our hypotheses of interest, we begin our analysis with a brief overview of the effects of more foundational organizational characteristics: their organization name, issue area, and funding sources. Brand recognition appears to be a powerful heuristic for donor decision making. Respondents were substantially more likely to prefer an organization when it was identified as the Red Cross, with a median posterior marginal mean of 34.9% (95% cred. int. = [0.339, 0.359])—ten percentage points higher than the 25% probability that would be expected if respondents selected an organization at random. When using Amnesty International as the reference category, the AMCE for the Red Cross is 12.3 percentage points (95% cred. int. = [0.110, 0.136]; \(p_d\) = 1.00). Other organizations see much smaller marginal means and AMCEs. Compared to Amnesty International, Greenpeace causes a small 1.4 percentage point increase ([0.002, 0.026]; \(p_d\) = 0.99) and Oxfam causes a small 2.0 percentage point decrease ([−0.031, −0.008]; \(p_d\) = 1.00) in the probability of selecting an organization. The Red Cross brand name heuristic is the strongest of all the experimental treatments and features, signifying the organization’s brand power and goodwill among potential donors. This finding also reflects previous research on the importance of nonprofit image management, which attributes the Red Cross’s longevity to its powerful brand, among other factors (Torres, 2010).

The issue area an organization works on also serves as a heuristic for donors. As seen in the marginal means in Figure 1, organizations focused on human rights and emergency response are more popular than those working on issues related to the environment or refugee relief. When using emergency response (the most popular issue) as the reference category for AMCEs, working with human rights causes a 1.2 percentage point decrease ([−0.025, 0.000]; \(p_d\) = 0.97), while environmental and refugee relief issues see 4.2 ([−0.054, −0.029]; \(p_d\) = 1.00) and 5.6 ([−0.068, −0.044]; \(p_d\) = 1.00) percentage point decreases, respectively. To put these effects in context, these effects are smaller than the Red Cross effect and a little larger than the Oxfam and Greenpeace effects.

Finally, an organization’s primary funding source also serves as a reliable donor heuristic. Organizations that are funded by many small donors are substantially more popular than those funded by government grants or a small group of wealthy donors—when compared to many small donors, both government and wealthy individual funding cause 3.5 and 4.1 percentage point decreases in the probability of selection ([−0.046, −0.025]; \(p_d\) = 1.00 and [−0.052, −0.031]; \(p_d\) = 1.00). These effects follow existing research on donor efficacy (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021)—when donors know that an organization is funded by others like themselves and that the marginal benefit of their individual donation is important, they are more likely to donate. In contrast, when donors know that an organization’s funding does not come from the public and instead comes from a few wealthy donors or large government grants, the marginal benefit they receive from donating decreases and they are less likely to donate. Donors therefore appear to be motivated by some degree of personal efficacy.

Effect of transparency and accountability

Having explored the effects of general organizational characteristics on the propensity to donate, we can test our first hypotheses and examine the effects of our treatments of interest. As seen in the marginal means in Figure 1, both transparency and accountability are strong signals of organizational deservingness. Respondents strongly prefer organizations that engage in either transparency or accountability—both treatments have a posterior marginal mean of roughly 30% compared to a baseline equally-at-random probability of 25% (transparency: 0.307; [0.299, 0.314]; accountability: 0.306; [0.298, 0.313]). The AMCEs for each treatment show a roughly 10 percentage point increase in the probability of selection compared to organizations that do not engage in transparency or accountability (transparency: 0.103; [0.095, 0.112]; \(p_d\) = 1.00; accountability: 0.101; [0.092, 0.110]; \(p_d\) = 1.00). This effect is nearly the same order of magnitude as the Red Cross effect—an NGO that chooses to be more transparent or that takes steps to demonstrate greater accountability can expect to see an increase in the probability of selection equivalent to the boost of the brand name effect associated with the Red Cross. As predicted, we thus find strong support for both H1a and H1b: if NGOs are financially transparent or engage in accountability practices, then individual private donors are roughly 10 percentage points more likely to donate to them. Donors appear to reward NGOs for their efforts to disclose their funding and be more transparent.

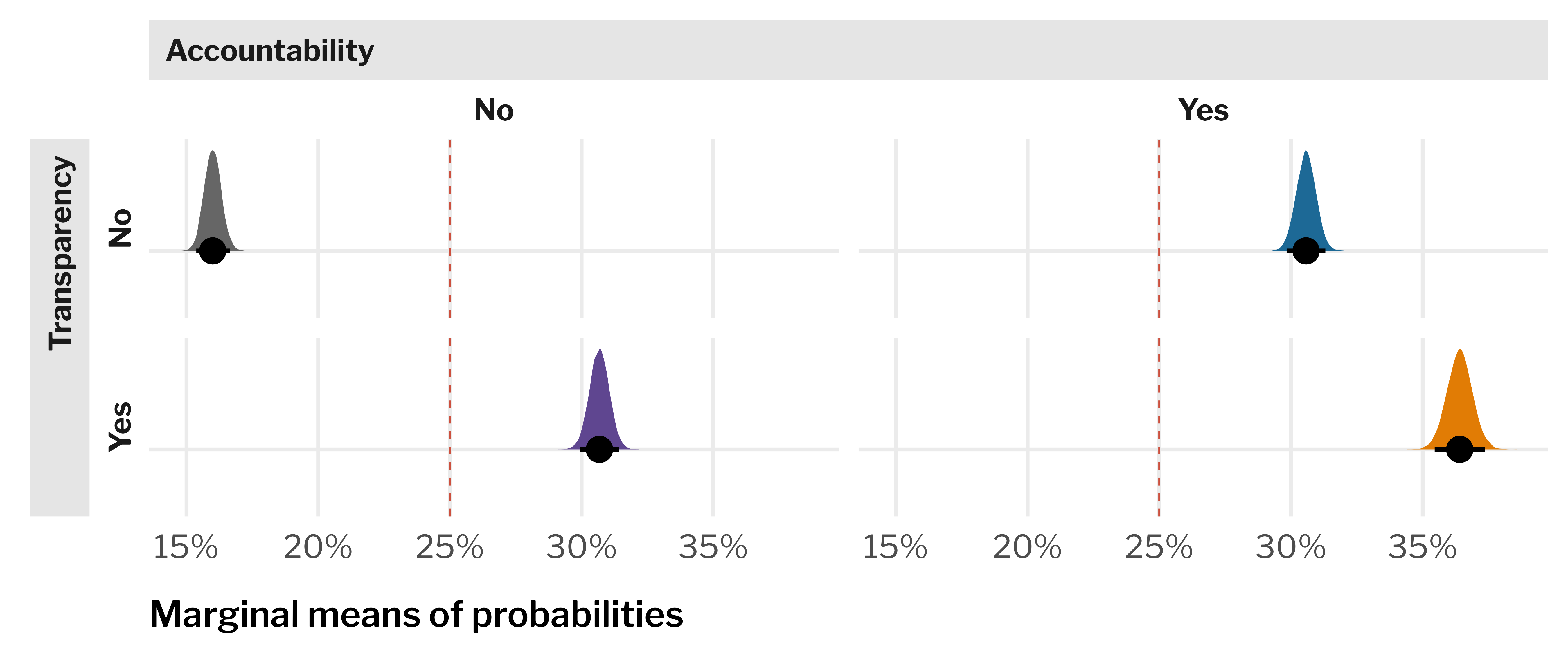

There is also some evidence that these two effects are equivalent and perhaps interchangeable. Figure 2 (and Table A8) shows the posterior marginal means for all four combinations of possible levels of transparency and accountability. When respondents see both as “no” simultaneously, the estimated marginal mean is lower than any of the individual treatments in Figure 1, at 16.0% ([0.154, 0.166]), or 9 percentage points lower than the baseline probability of 25%. When either transparency or accountability is set to “yes”, the estimated marginal mean is essentially identical at 30.7% and 30.6%, respectively. When both treatments are set to “yes”, the estimated marginal mean is 36.4% ([0.355, 0.373]), which is roughly the same as the overall estimated marginal mean for the Red Cross. Holding all other treatments constant, the effect of transparency and accountability practices on their own are generally the same, and when combined, the overall favorability of the organization increases substantially. This could indicate that donors do not care about which specific type of organizational practice an NGO engages in and that instead they are looking for some sort of signal that the organization is following best practices in transparency or accountability.

Effect of restrictions

To test our second hypothesis regarding structural heuristics, we explore the effect of an NGO’s host country conditions on the propensity to donate. Contrary to our expectations, respondents appear to prefer donating to NGOs with friendly host government relationships, with a marginal mean of 31.3% (compared to a baseline of 25%; [0.305, 0.322]). Respondents are less likely to donate when an organization is criticized by its host government, and far less likely when an organization faces restrictions. Compared to other treatments, an organization facing restrictions elicits a similar negative preference among potential donors as an organization without transparency or accountability measures. However, an organization with a friendly relationship with the host government leads potential donors to perceive it as equivalent to engaging in transparency or accountability.

In addition to these overall trends in preferences, we can measure the causal effect of moving from friendly NGO–government relations to a more antagonistic relationship. Using friendly relationship as the reference category, facing criticism by the host government causes a 6.9 percentage point reduction in the probability of selection ([−0.080, −0.059]; \(p_d\) = 1.00). Participants respond more strongly as the relationship becomes more conflictual and restricted—an NGO facing restrictions on its work sees a 10.4 percentage point reduction ([−0.115, −0.094]; \(p_d\) = 1.00) in support. We thus find strong evidence against H2: if NGOs face restrictions abroad, individual donors are less likely to donate to them. For context, the causal effect of facing restrictions is the same magnitude as the Red Cross branding effect, but in the opposite direction—donors seem to penalize NGOs facing criticism to the same extent that they reward the Red Cross. This result is surprising, but clarifies findings in previous research. In a similar vignette-based experiment, Chaudhry & Heiss (2021) find no substantial effect of legal restrictions on the probability of donation, and any substantive crackdown-related effects interact with and are dampened by other treatments like NGO issue area or funding source. This negative effect might also be related to the notion of donor efficacy. When deciding how to maximize the impact or marginal benefit of their individual donation, donors look for signals that their money will make a difference. Transparency and accountability practices, in addition to knowing that other individuals regularly support the organization, all act as heuristics of efficacy. An NGO facing criticism or restrictions abroad, on the other hand, may signal that potential donations could be used for legal fees, or signal that the NGO had perhaps done something to deserve the legal limitations it faces. These restrictions thus serve as a negative heuristic, signaling that donations might not be used as effectively as donors might hope.

The interaction between transparency, accountability, and restriction

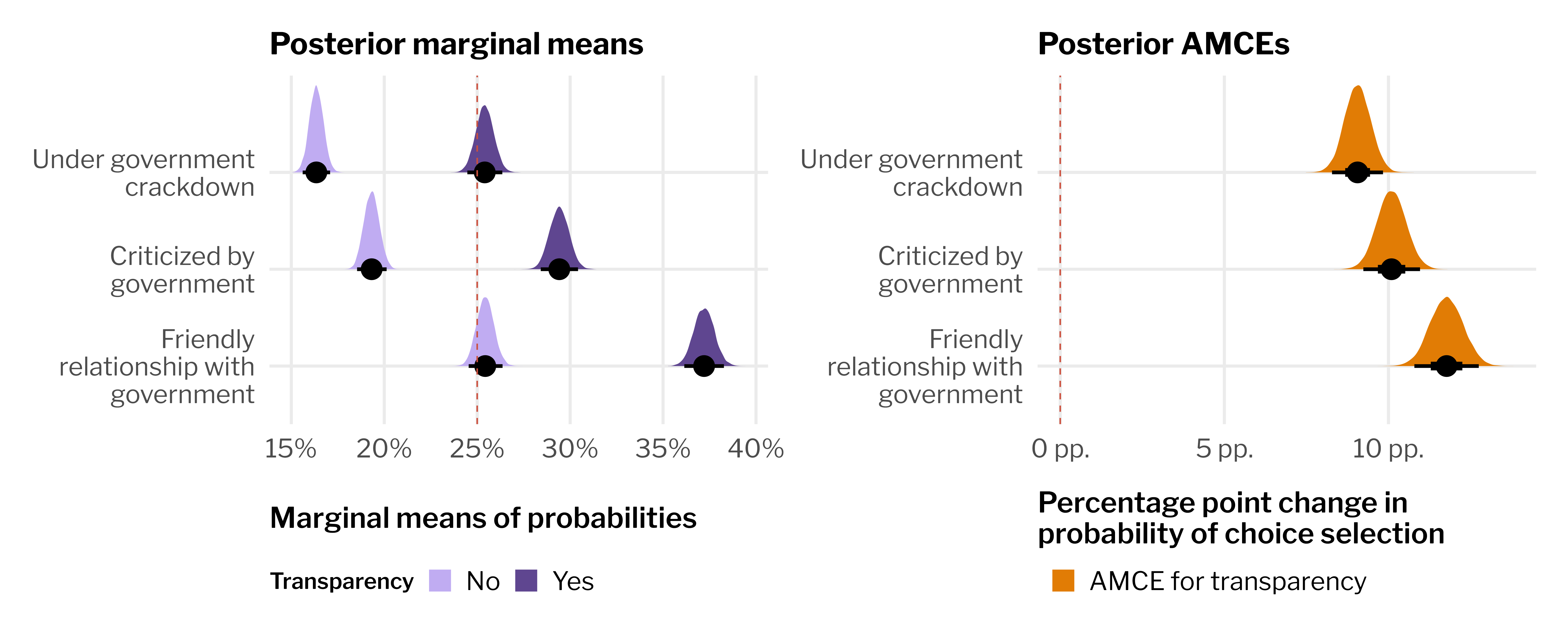

Financial transparency and accountability practices both have a positive (and likely interchangeable) effect on NGO favorability, while government criticism and restriction have a negative effect and discourage potential donors from donating. For our third hypothesis, we posit that these heuristics also interact with each other. This is confirmed in Figure 3 (and Table A9)—the estimated posterior marginal means for different relationships with host governments move in the same direction regardless of whether an organization engages in transparency practices:6 organizations with no conflict are most preferred, while organizations facing restrictions are least preferred. Transparency practices in the presence of restrictions have two general effects. First, engaging in transparency offsets most of the negative effect of facing hostile civic environments. The estimated marginal mean for an organization with friendly host government relationships and no transparency is 25.4%, which is equivalent to the estimated marginal mean for an organization facing government restrictions that does engage in transparency. On average, donors are indifferent to both situations—again, a marginal mean of 25% represents the probability of selecting an organization at random—but the presence of transparency shifts NGOs facing restrictions from negatively preferred to indifferent, while the absence of transparency shifts NGOs with friendly relationships from positively preferred to indifferent. From a practical perspective, this suggests that NGOs operating in hostile civic environments can focus on improving specific organizational practices to offset the negative signals that accompany their legal difficulties.

Second, worsening host government relationships weaken the positive effect of transparency. On its own, as seen in Figure 1, engaging in transparency causes a 10.3 percentage point increase in the probability of a respondent selecting an organization. The right panel of Figure 3 (and Table A9) shows how the causal effect of transparency changes across different types of government relationships. These AMCEs represent the difference in the estimated posterior marginal means of the two levels of transparency in the left panel. The effect shrinks as relationships become more negative: under friendly conditions, the median posterior AMCE of transparency is 11.8 percentage points ([0.108, 0.128]; \(p_d\) = 1.00); when an NGO is criticized, the transparency effect is 10.1 percentage points ([0.092, 0.110]; \(p_d\) = 1.00); when an NGO faces hostile restrictions, the effect drops to 9.1 percentage points ([0.083, 0.099]; \(p_d\) = 1.00). The causal effect remains substantially positive regardless of the relationship—even under the worst conditions, engaging in transparency causes a 9 percentage point boost—suggesting that NGOs facing crackdown can still increase their favorability with donors by signalling their commitment to transparency and accountability.

Discussion

These results have two important practical implications for NGO operations, fundraising, and survivability at a time when many INGOs are dealing with hostile host governments. First, while NGOs have little to no control over the legal environments of their host governments, they do have control over organizational practices such as transparency and accountability, and more importantly, public perception of these organizational characteristics. As a result, they may need to rely entirely on improving individual donor perceptions of organizational transparency and accountability and emphasizing the need for private donor funds at a time of shrinking civic space. These results provide insight into the importance of different framing or informational heuristics that can motivate such individual donor giving. In addition to voluntarily emphasizing or sharing this information with likely donors, nonprofits could also potentially brainstorm how to get more positive media exposure regarding these characteristics in restrictive civic environments. Moreover, we find that nonprofit transparency and accountability practices share the same causal effect, implying that donors might see these as interchangeable concepts.

Second, our results also highlight the importance of brand recognition and goodwill—respondents were more likely to prefer donating to an organization when it was identified as the Red Cross, a signal to the ubiquity of its brand across the globe and its emphasis on neutrality in hostile environments. Previous research shows that both brand awareness and brand trust are critical to non-involved consumers (Yen et al., 2023)—in this case, donors who have previously not donated to an organization. Others show that donors are loyal to brands whose values are congruent to their own (Sargeant et al., 2008). Our results thus have important implications on why nonprofits in hostile environments should focus on building brand awareness, as well as highlighting their values—to engage both likely and less likely donors.

Conclusion

Over recent years, governments globally have systematically restricted NGOs using legal means. This trend of closing civic space has important implications for local and international NGOs as well as donors. Recent research has analyzed the impact of this crackdown on public or official aid donors (K. Dupuy & Prakash, 2018; Herrold, 2020; Right et al., 2022). However, we know relatively little about how state repression of NGOs affects the preferences of foreign private donors (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021). Unlike state donors, individual donors have different motivations for engaging in philanthropy, and they may not necessarily withdraw or reduce support for NGOs facing harassment abroad. This is important because private philanthropy towards organizations working in international affairs continues to grow—following a decades-long trend, from 2021 to 2022, individual giving to nonprofits in international affairs grew by nearly 11% in the US (Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, 2023).

Given the increasing hurdles faced by these nonprofits, how do individual donors in the US feel about donating to legally besieged NGOs abroad? How does the effect of organization-level factors such as financial transparency and accountability compare with more structural-level factors such as host country civic environments in individual donors’ preferences to donate? Using a conjoint experiment of likely donors in the US, we find that organizational practices like financial transparency and accountability increase individuals’ preferences to donate to NGOs. Learning about host government criticism and restrictions against NGOs decreases the likelihood of donation by itself; however, financial transparency and accountability protect against this dampening effect, increasing the probability of philanthropic donations by nine percentage points under the worst conditions of legal crackdown. Our results highlight the importance of organizational characteristics like transparency and accountability even in an era of closing civic space.

Our results also have multiple important theoretical implications that should be explored in future research. First, future research should test how well these results map on to elite individual donors and foundations—not just the average private donor. As large foundations are more likely to publish data about their giving than the average private donor, it may be possible to determine how the changes in preferences elicited by these heuristics translate into actual donation behavior. Second, it is also important to test how these findings translate to non-American populations. Due to structural differences in the European nonprofit sector, where NGOs rely less on government funding and more on private funding (Stroup, 2012), donors are likely motivated by different concerns. Third, many states use negative rhetoric designed to sow mistrust between these groups and communities that support them. While donor responses have largely focused on navigating and adapting to legal restrictions, the use of such rhetoric raises broader questions about research and policy in the nonprofit sector: how is such rhetoric changing public attitudes and donations towards these groups? Are the effects of transparency and accountability found in this paper still likely to hold true if the home country also starts smearing these NGOs? Finally, though this paper examined legal crackdowns on INGOs, this issue is even more challenging for local NGOs in Global South countries, where individual donors might avoid giving to organizations focusing on contentious causes such as advocacy, media freedom, and anti-corruption initiatives due to unfavorable tax benefits or fear of retribution (Brechenmacher, 2017; K. E. Dupuy et al., 2015). Future research should examine how local NGOs can overcome individual foreign donors’ concerns about host governments’ criticisms of and crackdown on these groups.

Statements and declarations

Data availability

All data and replication code is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14721277 and at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/R59XZ.

We prereigstered our hypotheses and research design at the Open Science Framework (OSF). The full version of the OSF preregistration protocol is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HSBYD; a condensed version is included in the online appendix. We also include a list of deviations from the preregistration in the online appendix.

Ethical considerations

This experiment was approved and deemed as exempt by the human subjects research committees at both Christopher Newport University (1436622-1), Brigham Young University (E19135), and Georgia State University (H19644).

Consent to participate

We obtained written informed consent from each survey participant. The full text of the consent statement is included in the online appendix.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Supplementary material

A companion statistical analysis notebook with a more complete description of the data, modeling details and diagnostics, and additional explanations of the Bayesian multinomial modeling approach, along with links to the data and replication code, is available at https://stats.andrewheiss.com/silent-skywalk/.

References

Footnotes

To be clear, we do not examine elite-level giving or philanthropy by wealthy donors in the US.↩︎

For instance, Charity Navigator lists multiple different accountability and financial metrics in an easily available user-friendly format on its website: https://www.charitynavigator.org/about-us/our-methodology/ratings/accountability-finance/↩︎

Crackdowns can also be violent. However, unlike administrative crackdowns, violent crackdowns are often hard to attribute to governments, since governments often outsource repression. Moreover, given the ubiquity of anti-NGO laws in recent decades, we focus on the impact of these legal crackdowns on donor preferences.↩︎

Our preregistration protocol is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HSBYD and in the appendix, and our data and reproducible code is available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/R59XZ. For clarity, we focus on our simplest, non-nested hypotheses, omitting many preregistered ones that overlap (e.g., the effect of branding and issue area and transparency and crackdown simultaneously). Following Willroth & Atherton (2024), we outline all the deviations from our preregistration protocol in the appendix.↩︎

We used real organization names rather than fictionalized names to allow the experimental task to better mirror reality (McDonald, 2020) and to reduce respondent cognitive burden when reflecting on organization characteristics (Majnemer & Meibauer, 2022).↩︎

We only show the interaction of transparency and crackdown in Figure 3. Given the near interchangeability of the two treatments, the interaction between accountability and crackdown is nearly identical. We include both transparency and accountability in Table A8.↩︎