Derogations, Democratic Backsliding, and International Human Rights During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Did states misuse international legal emergency provisions during the COVID-19 pandemic to justify human rights abuse or did they follow international human rights law? Many governments restricted citizens’ freedom of movement, association, and assembly during the crisis, raising questions about states’ commitments to international human rights law. Some states used derogations to communicate temporary suspension of international legal provisions in a proportional and non-discriminatory manner, while others did not. We explore the dynamics of democratic backsliding and derogation use during the pandemic. We find that backsliding states were more likely to issue human rights treaty derogations. These derogations had mitigating effects once issued. Backsliding states that issued derogations were more likely to communicate restrictions and were less likely to issue abusive and discriminatory policy during the pandemic. Derogations helped temper abuse in states not experiencing backsliding. However, derogations did not always protect against abuse and media transparency in backsliding states. These results lend support to the use of flexibility mechanisms in international law and find that most states did not use emergency derogations to heighten human rights violations. The study contributes to the understanding of how international legal measures may help mitigate elements of democratic backsliding during times of crisis.

human rights, international law, pandemic, derogation, democratic backsliding

Pandemic-era Democratic Backsliding and Treaty Behavior

Combating a deadly virus like COVID-19 required extraordinary public health measures that often conflicted with personal rights and freedoms. Globally, IOs were confronted with how to situate the crises within global governance and human rights frameworks (Comstock, 2024), as were national-level governments (Chaudhry et al., 2024). One way that states navigated the pandemic was to enact emergency measures. Internationally, states could commit to these emergency provisions via treaty derogations. Treaty derogations, or temporary suspensions of states’ international treaty commitments, are intended to allow flexibility to states while they are experiencing a crisis—which could be civil conflict, natural disaster, or a public health crisis. Derogations provide vital information to international and domestic monitoring bodies, interest groups, and advocates about which rights are suspended, for how long, and the reasoning behind these suspensions. This information allows actors—at least in principle—to challenge measures that are excessive, vague, or outlast the intended time frame of their implementation (Helfer, 2021). The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is the only treaty with universal UN membership that requires states to issue derogations when human rights are suspended during times of crises, making it the main focus of our empirical analysis. The ICCPR places clear limitations on state actions when derogating, including that they must be proportionate, non-discriminatory, and temporary. It also specifies certain rights as non-derogable and outlines a formal procedure for derogation: the emergency must be formally declared, and the UN Secretary-General must be notified.

Extant research on derogations has examined the kinds of states that are more likely to utilize them and the conditions under which they do so (Burchill, 2005; Hafner-Burton et al., 2011). This research finds that democracies are more likely to issue derogations and other post-commitment actions related to human rights treaties (Comstock, 2019; Simmons, 2009). Though the most frequent derogators are stable democracies and countries where domestic courts can exercise strong oversight of the executive and hold them responsible for breaches of human rights agreements, derogations—especially in the context of a long-lasting event like a pandemic (Helfer, 2021; Lebret, 2020)—are more concerning because of the tendency of some countries to turn into “serial derogators.” These countries generally derogate “without providing information about rights restrictions and in multiple consecutive years” (Hafner-Burton et al., 2011, p. 675). Other research has also found that governments frequently violate both derogable and non-derogable rights (Richards & Clay, 2012). This paper builds on research by examining the dynamics between democratic backsliding and state behavior as it relates to international human rights law derogations. Extending analysis to democratic backsliders allows us to understand how regimes experiencing democratic erosion or authoritarian resurgence might engage with these international legal actions.

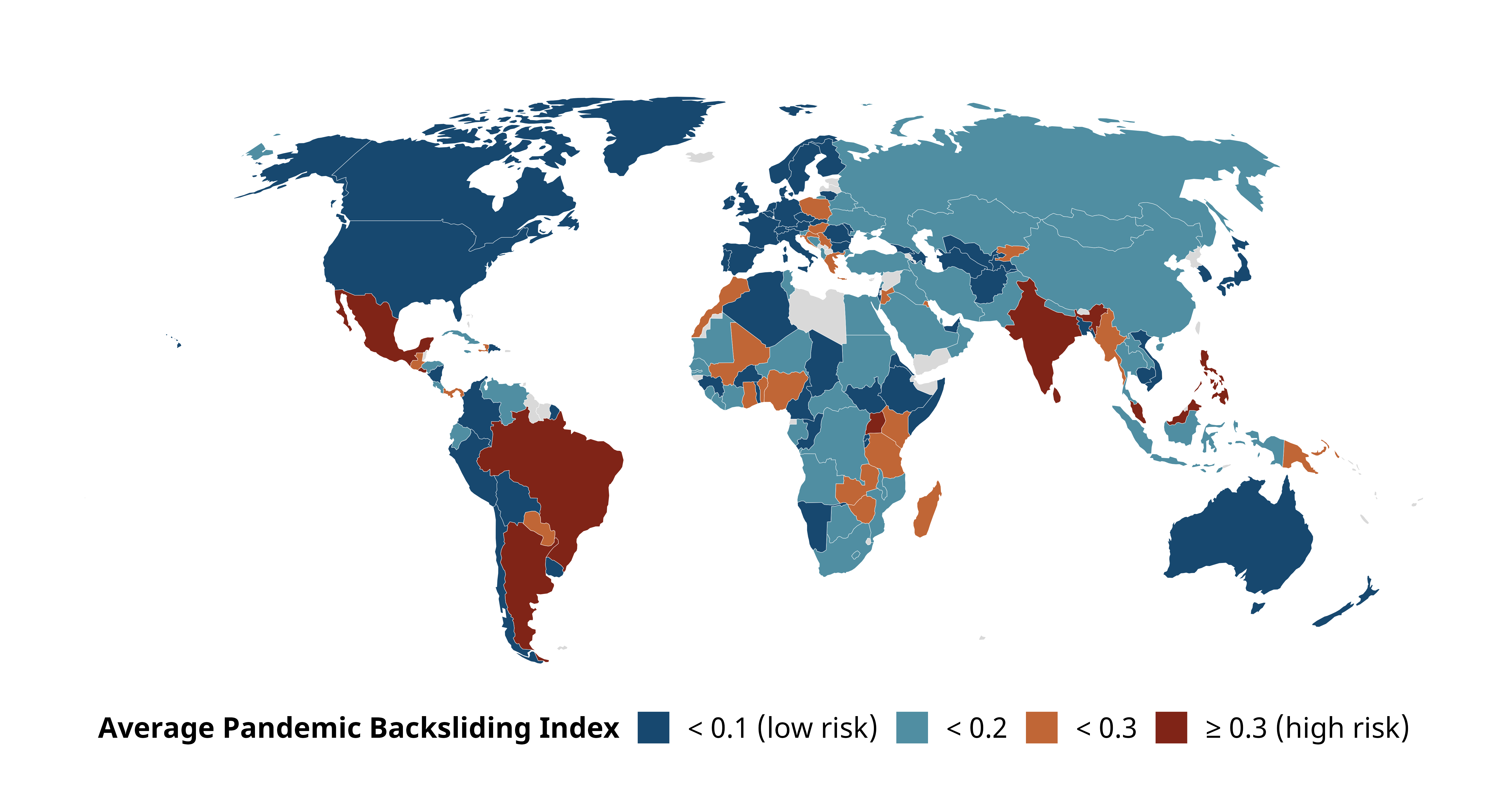

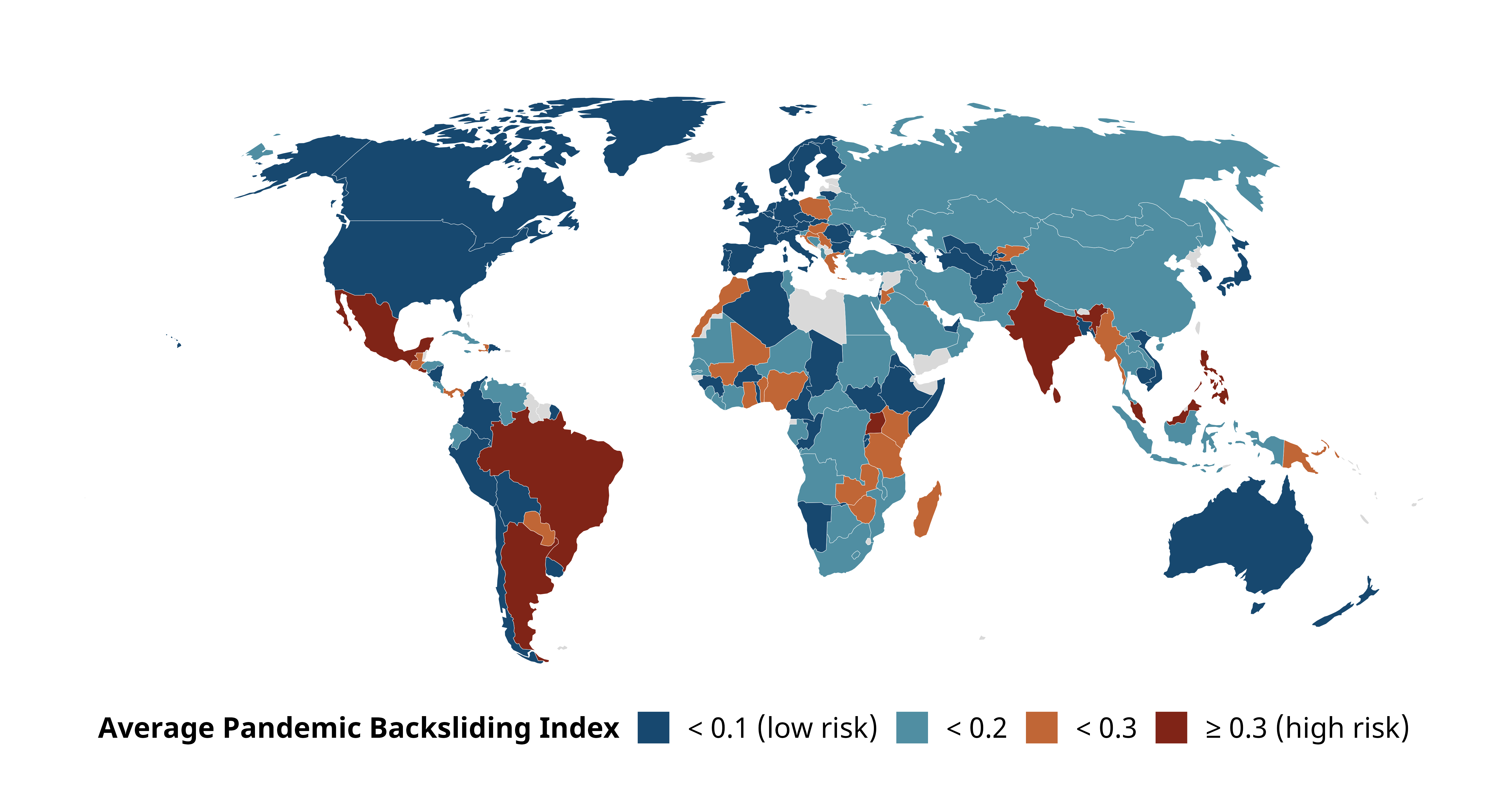

Global democratic backsliding was already in motion when the pandemic spread in March 2020 (Lührmann & Lindberg, 2020; Maerz et al., 2020). As of 2019, the share of countries experiencing democratic erosion more than doubled in the past decade compared to the decade before (IDEA, 2019), with only 8% of the world’s population living in countries becoming more democratic (Lührmann & Lindberg, 2020). Democratic backsliding is a particular subset of such erosion involving the intentional weakening of checks and balances, and the curtailment and rollbacks of civil liberties, political rights, personal freedoms, and a broad swath of human rights, in any state, regardless of regime type.1 Figure 1 demonstrates that North America and Western Europe generally had low risk of democratic backsliding during the pandemic. However, this does not indicate that there was no backsliding occurring. Researchers point to election manipulation and executive overreach in the United States as examples of democratic erosion (Williamson, 2023) and the European Union has responded via sanctions to curb democratic backsliding of member states (Blauberger & Sedelmeier, 2024). The higher risk areas included parts of South America, across Africa, India, and some parts of Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia. Overall, pandemic-era democratic backsliding was a global phenomenon. Figure 2 depicts states that issued pandemic-related derogations to the ICCPR. Most states do not issue derogations even during times of emergency, so the determinants of when they are issued are important to understand. Geographically, derogations were issued across different regions including South America, Africa, Eastern Europe, and some parts of Asia. They were not generally issued across North America or Western Europe.

International Human Rights Law, Democratic Backsliding, and Transparency in Crises

Did democratic backsliding shape how states participated within the international human rights regime, and specifically did the decline in democracy mean heightened, opportunistic abuse of international human rights law? From the literatures on international law, reputation, and democratic erosion, we draw several expectations about these dynamics. Namely, we emphasize the importance of transparency and legitimacy in the interplay between backsliding and derogations during the pandemic.

State regime type matters when exploring human rights and human rights law commitment. Democracies are more likely to ratify key human rights treaties (Simmons, 2009) and generally intend to comply with them (Chayes & Chayes, 1993; Simmons, 2009). When non-democracies ratify human rights treaties, they “seldom keep their promise” of compliance (Von Stein, 2016). Though we know that autocracies do participate in international human rights law through commitment and other legal actions following ratification (Boyes et al., 2024; Comstock & Vilán, 2024), treaty participation may be entirely strategic on the part of non-democracies. Such states may only ratify treaties to signal their resolve to domestic opposition groups (Hollyer & Rosendorff, 2011).

Existing research on regime transitions, human rights compliance, and commitment is informative for our expectations about backsliding states and legal engagement. Regime transition matters along several important fronts. Regimes transitioning toward democracy, or democratizing, are more likely to use the international human rights regime as a means of legitimation (Moravcsik, 2000), including through treaty commitment (Comstock, 2021). Though new democracies are more likely to commit to broad human rights conventions more quickly, they are also more hesitant to commit to human rights treaties with more demands (Dai & Tokhi, 2023). Regimes transitioning away from democracy—or experiencing democratic backsliding—are found to repress human rights more. Davenport (1999), for example, finds that the transition towards autocratization has a significant and positive impact on repressive behavior while democratization promotes more open governance. The strength of domestic democratic institutions, in particular, is important for these findings (Hill & Jones, 2014). Meyerrose (2020) argues that if IOs promote some domestic institutions but not others, backsliding can occur when domestic executives are empowered above other institutions. In examining democratic backsliding and human rights more specifically, Adhikari et al. (2024) find strong statistical support that democratic backsliding harmed human rights. The authors found that the degree or intensity of backsliding along with the length of the backsliding period contributed to further chances of human rights violations. Ginsburg (2019) suggests that international and regional courts may be a means for activists to resist the spread of national-level democratic backsliding. Mechkova et al. (2017) caution against interpreting democratic backsliding as too extensive of a trend, noting that most liberal and electoral democracies that declined were unlikely “to collapse so fully that it becomes an autocracy” (165). Rather, democratic character remains, at least in part, in these states experiencing democratic backsliding wherein the “normative power of democracy remains relatively strong” (168).

During times of crises, states may have different motivations about protecting their reputation and signaling transparency to both domestic and international audiences. Transparency about human rights can come in many forms, including clear websites, information about policy, and navigable institutions (Creamer & Simmons, 2013). Transparency can be a dimension of institutional design in international law (Bianchi & Peters, 2013) that impacts compliance with human rights law through increasing the understanding of norms and expectations (Chayes & Chayes, 1993), and can shape the perception of international institutions and governments during times of crises (Bruemmer & Taylor, 2013). In the context of international disasters, there has been an increasing push to provide information about the disaster and government response, though transparency is often provided only when a certain threshold of severity is reached (Riccardi, 2018).

Bringing these literatures together, we expect that states that issue derogations are more willing and capable of communicating to domestic and international audiences about potential and real rights restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Concerns about international reputation often shape behavior and are connected to the desire to obtain certain goals—these usually include some form of aid, trade, membership and holding office in IOs, and receiving higher rankings on performance indicators (Bush & Zetterberg, 2021; Kelley & Simmons, 2019; Levitsky & Way, 2010). Generally, when countries seek cooperation from the international community, they seek external legitimacy (Kelley, 2012) and will consequently abide by legal and normative commitments to uphold human rights and the rule of law.

Public international commitments, such as compliance with the ICCPR, can thus be an important way for states, especially those backsliding, to signal their intent to the international community, to agree to respect these rights moving forward. Human rights compliance can be a costly signal for the costs associated with both reaching human rights standards and the threat of penalty if the standards are not met (Moore, 2003). Human rights compliance and legal engagement provide information about states to others in the international community. More powerful or prominent states may feel the need to signal less given the information readily available about their interests and behavior (Moore, 2003, p. 890). However, states with less information available about their interests, commitment, and behavior can use human rights treaty signaling to convey that information to a broad, global audience.

States in regime transitions that still have elements of democracy intact may be particularly interested in preserving their reputations and find that communicating information during a global crisis is one means of doing so. In this case, issuing derogations may become of particular interest to backsliding states as a means to communicate interests about human rights. A state’s reputation at the time of action can shape how impactful signaling around human rights can be and also incentivize signaling (Guzman, 2008, p. 8). However, not all states are interested in protecting their international reputation (e.g., Benabdallah, 2019; Cooley & Nexon, 2020; Hackenesch & Bader, 2020). These states may choose to avoid derogating simply for the purpose of signaling that they do not accept international human rights regimes.

We posit that backsliding without derogating signals that the national government does not value its international reputation or is not institutionally capable of communicating transparently about potential and real restrictions and abuses during the pandemic. In other words, we expect that we can learn about international signaling and state behavior by examining the dynamics of how backsliding states used international law during a crisis. Examining behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic will provide insights into state signaling and intentions during the crisis.

| Derogation | No derogation | |

|---|---|---|

| Backsliding | Transparency about restrictions and violations | Low/no transparency about restrictions and violations |

| Motivations: Legitimation and reputation concerns | Motivations: Leader not concerned about reputation backlash | |

| No backsliding | High transparency about potential restrictions and violations | Limited/no transparency about restrictions and violations |

| Motivations: Strong rule of law and valuation of international regime | Motivations: Limited concern about reputation backlash and limited valuation of international regime |

From these literatures, we draw two hypotheses:

H1: States experiencing democratic backsliding will be more likely to issue derogations.

H2: States experiencing democratic backsliding that also issue derogations will be less likely to abuse human rights than states that only backslide.

To test these expectations, we conduct a series of quantitative analyses followed by a brief examination of illustrative cases mapping onto each quadrant of Table 1 (we include more detailed case studies in the appendix). From these series of tests, we provide a deeper understanding of motivations and behavior of states during times of a health crisis and global threats to democracy.

Methods and Data

We first quantitatively explore the dynamics between democratic backsliding, human rights treaty activity, and human rights behavior by creating a set of Bayesian regression models and generating predictions for typical or average countries, which allows us to better isolate the associations between different elements of state behavior. We include three sets of models that examine (1) the probability of treaty derogation during COVID-19, (2) the probabilities of different types of COVID-19 policy responses, and (3) the probabilities of different types of pandemic-era human rights responses. We look at the results of all three sets of models across four key conditions: states that did and did not face the risk of democratic backsliding and states that did and did not derogate from treaty obligations.

Variables included in models

We use weekly data from March 11, 2020, to June 30, 2021, for 139 countries during the first 69 weeks of the pandemic. Table A1 in the appendix lists the main variables we used across our models. To measure democratic backsliding, we use the Pandemic Backsliding Index (PanBack) from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (Coppedge et al., 2022; Edgell et al., 2020). PanBack measures the risk of democratic backsliding specifically during the pandemic, assessing how state responses to the pandemic violated democratic standards, based on the severity of different kinds of human rights violations. PanBack ranges from 0 to 1, with high values representing greater risk of backsliding. Following V-Dem, we dichotomize values and consider PanBack scores above 0.3 as high risk.

We measure treaty activity with a binary indicator of whether a state had formally suspended its ICCPR treaty obligations through derogation during a given week. We collected and coded this data from the United Nations Treaty Collection (United Nations, 2023). Finally, we include several other variables associated with both pandemic-era backsliding and derogations. We use four measures of pandemic severity each week: new cases, cumulative cases, new deaths, and cumulative deaths (World Health Organization, 2023). We also include weekly measures of specific government public health policies (Hale et al., 2021) and quarterly measures of the severity of human rights and policy outcomes (Edgell et al., 2020). We capture a state’s general respect for the rule of law and transparency in enforcement with V-Dem’s Rule of Law Index. Because this value is only reported annually, it acts like a country-level fixed effect in our models, representing the overall level of respect for the rule of law in a state over time. To account for differences in pandemic responses over time, we also include a weekly time trend.

Modeling strategy

We use a Bayesian approach to explore the uncertainty associated with state behavior during the pandemic—we include detailed specifications of our models, priors, and sampling strategy in the appendix. For binary outcomes, we use logistic regression; for categorical outcomes, we use ordered logistic regression. Both of these families of models provide coefficients on a logged odds scale, which can make interpretation difficult. To aid in the interpretation of results, we calculate conditional predicted probabilities by holding all explanatory variables constant (representing a typical country/week) and varying only derogation status and backsliding risk. We then calculate the contrasts between these predicted probabilities to determine the average differences associated with derogations and backsliding. We present these predicted probabilities graphically where possible, and we include the complete log-odds-scale results in Tables A2–A4 in the appendix. Rather than reporting individual point estimates, we report 95% credible intervals. We also report the posterior probability that the predicted contrasts between derogation status and/or backsliding risk are above or below zero.

Analysis

Explaining COVID-19 derogations

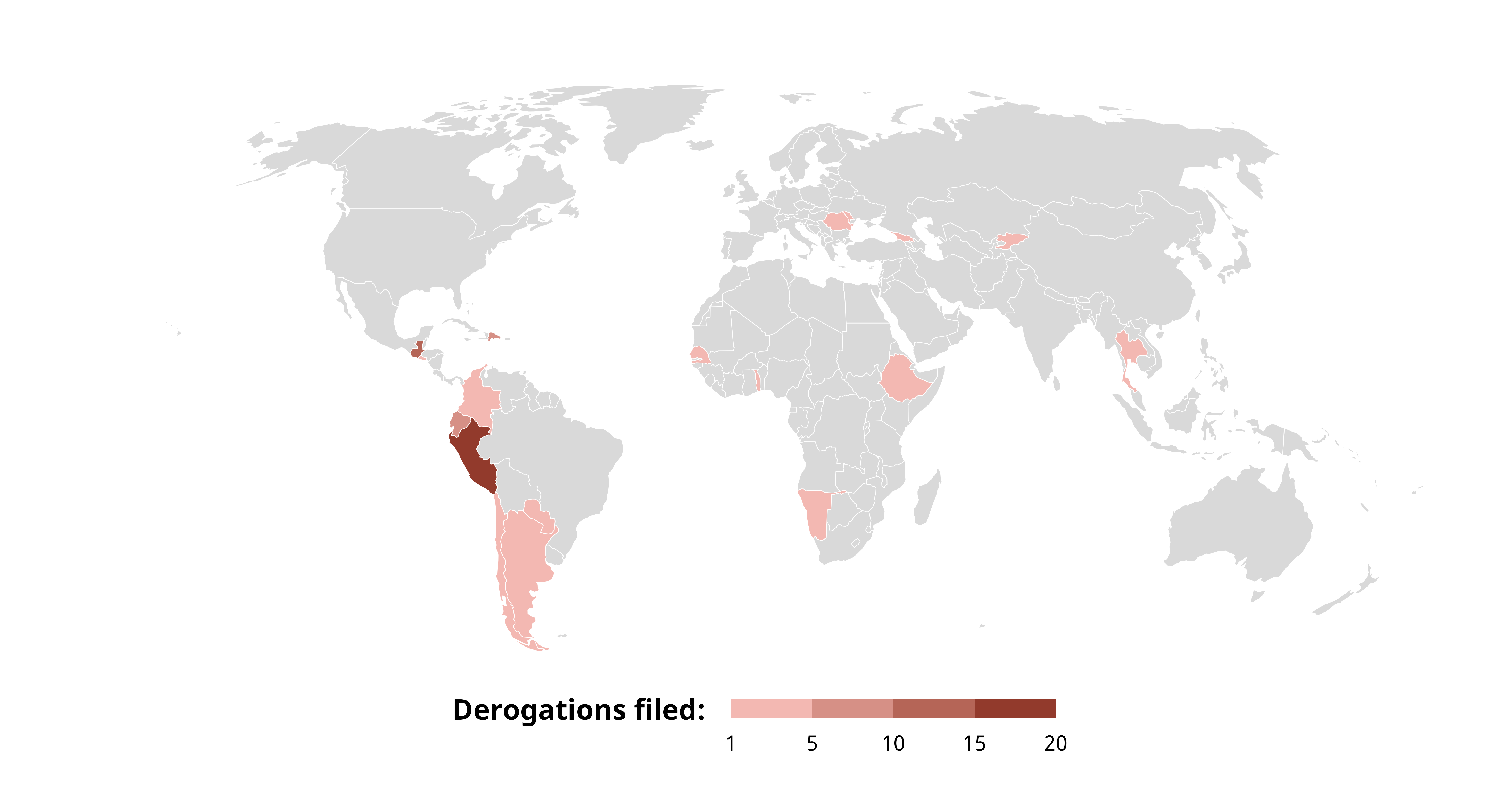

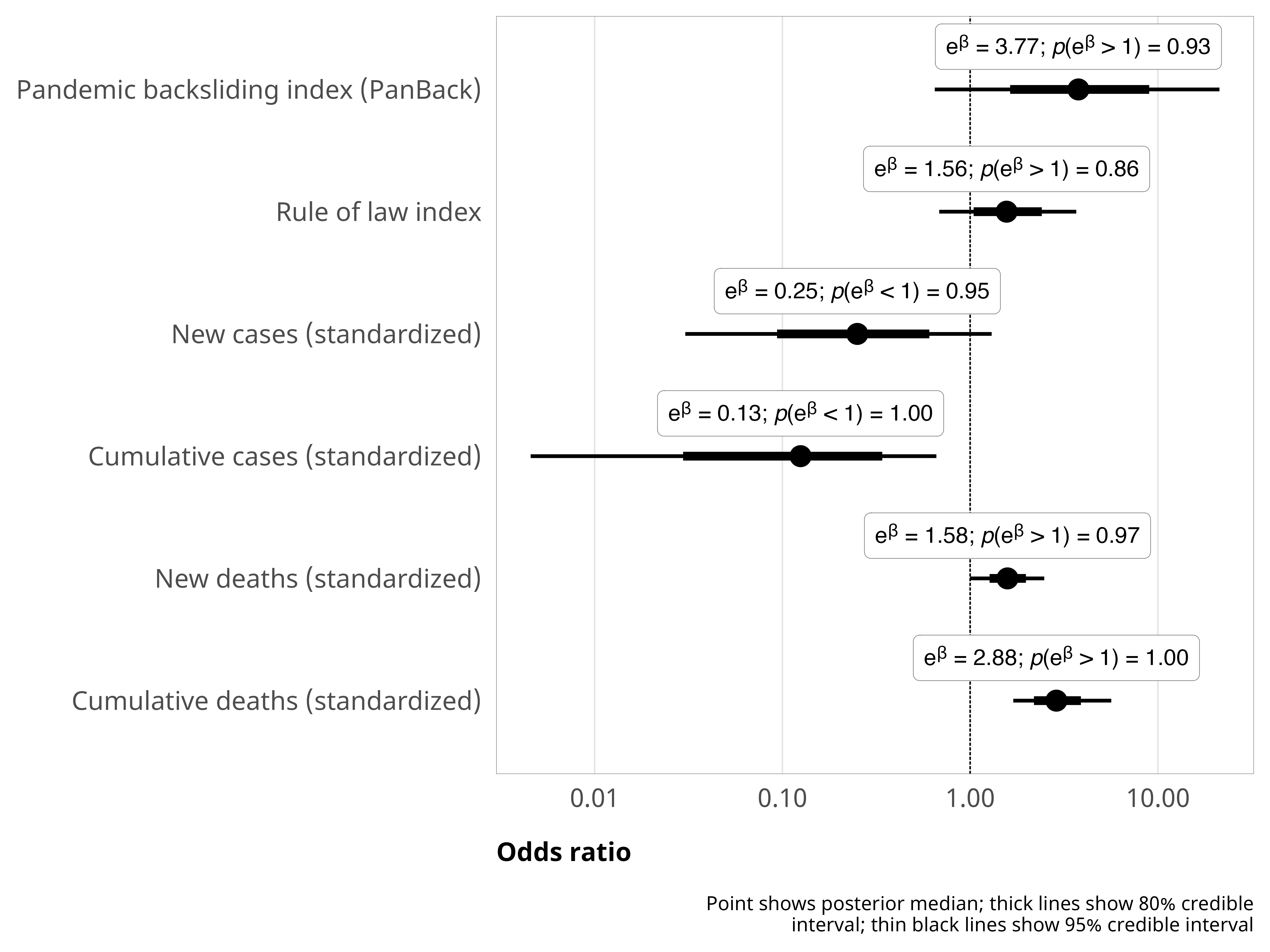

We first explore whether backsliding states are more likely to issue derogations from international human rights treaties. Figure 3 presents the odds ratios from a model predicting ICCPR derogations (complete results are in Appendix Table 2). States that experienced pandemic backsliding were nearly four times more likely to file derogations (\(e^\beta = 3.85\); \(p[e^\beta > 1] = 0.92\)). This is distinct from states with strong domestic institutions as measured by the rule of law index, which was positively associated with the probability of derogation, but not statistically significant (\(e^\beta = 1.56\); \(p[e^\beta > 1] = 0.86\)). Looking at the measures of health crisis, a one standard deviation increase in new and cumulative COVID cases is associated with a 76% and 87% decrease in the likelihood of derogation, respectively. In contrast, an increase in new and cumulative COVID deaths is associated with a ≈50% higher and a nearly three times greater likelihood of derogation, respectively. Taken together, we see that more severe measures which captured increased intensity of both (1) democratic violations contributing to backsliding and (2) COVID deaths were the indicators that prompted states to issue pandemic-related derogations. Backsliding states were more likely to issue derogations to the ICCPR, limiting legal obligations to international human rights law during the pandemic.

To explore whether democratic backsliding had an overall impact on legal behavior toward international human rights treaties, Figure 4 descriptively shows the count of all human rights treaty actions by states, divided by type of filing. Derogations are overwhelmingly the most common type of international treaty action issued during the pandemic. In the appendix, we run a model that predicts non-derogation actions (such as ratifications, reservations, and declarations) using the same covariates used to predict ICCPR derogations, and find that the rule of law index is the only factor that significantly predicts non-derogation human rights treaty actions—backsliding is not substantially associated with other kinds of treaty actions. Examining these treaty actions as a dependent variable allows us to test whether democratic backsliding states participated with international law, broadly, in different ways from their counterparts and/or had a unique set of behaviors with more critical legal actions such as derogations. These findings together may indicate that for general, non-emergency legal actions, strong domestic rule of law and institutions generally matter for international legal behavior, but during times of crisis, other factors are at play. Backsliding behavior did not shape states’ legal engagement with all human rights treaties—rather, states specifically and uniquely responded to the pandemic with targeted derogations.

Explaining COVID-19 restrictions

Next, we examine how backsliding risk and derogation behavior are associated with different types of emergency policies. Figure 5 presents the conditional predicted probabilities of different levels of enforcement of internal movement, public transportation, and stay-at-home emergency measures in a typical country-week. A consistent pattern of government responses emerges across all three types of emergency measures. For internal movement (Figure 5, panel A), states with a low risk of backsliding that did not derogate had the highest probability (34–36%) of not imposing any travel restrictions and the lowest probability (44–47%) of having strict restrictions in place. Low-backsliding-risk states that derogated, in contrast, were substantially more likely to have restrictions in place and far less likely to have no or minimal restrictions. Among states with a high risk of backsliding, the pattern of the probability of imposing internal movement restrictions for non-derogating states appears relatively similar to the pattern in low-risk, derogating states, with a 57–64% chance of imposing restrictions for non-derogating states. For backsliding states that derogated, having restrictions in place is overwhelmingly the most likely outcome with a probability between 83–99%, with both no measures and recommendations to not travel only 1–8% likely.

The predicted probabilities for public transportation measures and stay-at-home restrictions demonstrate similar patterns (Figure 5, panels B and C). Non-backsliding, non-derogating states are the most likely to have no emergency measures (46–49% and 26–28%, respectively) and least likely to impose the harshest restrictions (14–16% and 4–5%, respectively). For non-backsliding states, having a derogation in place is associated with a substantially higher probability of requiring the closing of transportation systems (31–39%; twice as likely) and requiring residents to stay home (21–28%; nearly two-thirds as likely). States with a high risk of backsliding that do not derogate appear roughly similar to non-backsliding, derogating states, while high-risk states that derogated are the most likely to require closing (40–68%) and the least likely to have no emergency measures at all (6–18%). Derogations appear particularly important for stay-at-home measures, which are the most individualized of the three emergency measures here (i.e. residents are constrained to their homes vs. prohibited from traveling between cities or using public transportation). More democratic, non-backsliding states appear hesitant to impose requirements to stay-at-home, and the states that did so reinforced this emergency violation with a derogation. States at greater risk of backsliding were more willing to impose these restrictions without derogations, and those that derogated had the highest probability of strict emergency measures.

There is a consistent pattern across the four types of states: low-risk, non-derogating states have the lowest probability of imposing any emergency measures; high-risk, derogating states have the highest probability of imposing strict measures; low-risk, derogating states and high-risk, non-derogating states have roughly similar probabilities of the strictness of emergency measures. This could indicate that at a baseline, backsliding states were more willing to enact restrictions than their non-backsliding counterparts. It can also imply that both low-risk and high-risk states used derogations as a method to enact stronger pandemic measures, signaling that they were either taking the pandemic more seriously, or possibly using derogations as cover for using stronger restrictions (Chaudhry et al., 2024).

Explaining COVID-19 human rights violations

While there is a consistent pattern in how democratic backsliding and treaty actions are associated with pandemic-related emergency measures, there is much more variation in how democracy and derogations influence a state’s respect for human rights during the pandemic. Figure 6 presents the conditional predicted probabilities of different types of human rights violations in a typical country-week.

We find that states with a high risk of backsliding are more likely to abuse human rights. Earlier, we found that backsliding states had a higher baseline than non-backsliding states for imposing pandemic-related emergency measures. We find similar trends with human rights abuses. In all the human rights outcomes we observed, states with a high risk of backsliding have a substantially high probability of human rights abuses. For instance, states with a low risk of backsliding have more than a 90% probability of imposing discriminatory policies, while states with a high backsliding risk only have a 45–52% chance of seeing no discriminatory policies, and have high probabilities of minor, moderate, or major violations. Violations of non-derogable rights are exceptionally rare in non-backsliding states (with a 95–100% chance of no violations), while such abuses are predicted to occur a quarter to half of the time in backsliding states. States with a low risk of backsliding also see lower probabilities of abusive enforcement and media restrictions than their high-risk counterparts. Backsliding states are more likely to not specify time limits for emergency measures, though the difference is less visually striking than the other human rights outcomes in Figure 6—states at risk of backsliding are 2–9 percentage points (for states with no derogations) or 4–24 percentage points (for states with derogations) percentage points more likely to have no time limits than states with low risk of backsliding (\(p[\Delta > 0] = 1.00\)). Perhaps not surprisingly, states that experienced backsliding were significantly more likely to use discriminatory policy and media restrictions during the pandemic.

Derogation status interacts with backsliding risk—among states with a high risk of backsliding, derogation is associated with better outcomes for several of the human rights violations we modeled, providing partial support for our second hypothesis. Among states at risk of backsliding, those that do not derogate have a range of probable levels of implementing discriminatory policies (Figure 6, panel A) and only a 45–52% probability of no violations, while those that do derogate have a nearly 100% chance of avoiding discriminatory policies. The difference is similar for abusive enforcement (Figure 6, panel C). States at risk of backsliding are most likely to engage in minor (≈25%) or moderate (≈33%) abusive enforcement regardless of derogation status, but the distribution of possible outcomes shifts substantially at the extremes when states derogate. The risk of major abusive enforcement drops from 21–26% to and the probability of no violations jumps from 16–21% to 23–44% for derogating states. The difference appears similar—though not significant—for the violation of non-derogable rights. Derogating backsliding states are roughly five percentage points less likely to violate these rights, but the difference is not significant (\(p[\Delta > 0] = 0.70\)).

Derogation status also matters for the risk of not having time-limited emergency measures. For backsliding states, derogation is associated with a 1–20 percentage point higher probability of having time-limited measures (\(p[\Delta > 0] = 0.95\)), while in non-backsliding states there is a 16–21 percentage point difference, which is larger and more precise (\(p[\Delta > 0] = 1.00\)). This difference can be directly attributable to derogations, since the derogation process requires that states specify time limits for their emergency measures.

Some trends go against our expectations. Media restrictions are the only human rights outcome where derogations do not behave as expected for backsliding states—states that do not derogate have an 88–92% probability of major media restrictions and a 95–100% chance of major restrictions when derogating. We hypothesized that derogating and backsliding states would care about legitimation and reputation, but it seems that these concerns do not apply to censorship and media restrictions. Derogations are associated with better human rights outcomes in states with a low risk of backsliding for all measures except abusive enforcement, where the probabilities of minor, moderate, and major violations increase by 3–10 percentage points (Figure 6, panel C).

A Closer Look at States by Derogation and Backsliding Behavior

We briefly consider four states as illustrative cases of varying derogation and democratic backsliding behavior to better unpack how democratic backsliding and derogation interaction (or lack thereof) may have influenced state behavior during the pandemic. Earlier in the paper, we posited that transparency about restrictions and violations would vary across states based on derogation and backsliding behavior. Table 2 situates the cases across backsliding and derogation status. We selected cases that depict both regional variation and low/high risk of backsliding. Including extreme cases should be an “easy test” of the influence of backsliding on human rights violations and other behaviors if democratic backsliding has an impact. The four cases illustrate derogations’ mitigating effect in states experiencing democratic backsliding and those that did not. Derogating states in both backsliding scenarios had concerns about maintaining international reputation and legitimacy (Armenia, Guatemala), and derogations helped them communicate their pandemic measures in a more or less transparent manner. However, states not as interested in protecting their international reputation, especially in the perspective of Western states, were less likely to use derogations as a means to communicate their intentions about pandemic measures (India, Hungary). These states subsequently engaged in more abusive and discriminatory enforcement of such measures. The dynamics illustrated in these cases overall support the purpose of derogations in international law. However, state motivations for declaring derogations among states both experiencing backsliding or not are more complex and merit further investigation. A full discussion of each of the cases is included in the appendix.

| Issued Derogations | No Derogations | |

|---|---|---|

| a PanBack > 0.3 | ||

| Experienced High Risk of Backsliding a | Guatemala | India |

| Did Not Experience High Risk of Backsliding | Armenia | Hungary |

Conclusion

We set out to explore the dynamics between international legal engagement via derogation and democratic backsliding. Given the global trend in democratic backsliding and concerns about the robustness of democratic institutions, we examined how and why states used legal loopholes to limit their international human rights law obligations. We argued that the interaction between these two phenomena could provide insights into state behavior based, in part, on transparency around crises.

The statistical findings indicate a few key takeaways. First, derogation behavior was distinct from other types of human rights treaty legal behaviors during the pandemic. States that did not typically submit treaty actions did so intentionally during the pandemic to signal the restriction of human rights obligations to the ICCPR. Second, backsliding states still engaged in signaling crisis restrictions on rights via the submission of derogations. Democratic backsliders did not withdraw from participating with the international human rights regime—they still saw some value in participating. Third, backsliding was associated with increased odds of abusive and discriminatory practices during the pandemic. Fourth, and importantly, the interaction between derogations and backsliding appears to have potentially mitigated some of the abusive behaviors during the pandemic.

What these findings point to is that democratic backsliding is a complex phenomenon—states experiencing backsliding impose discriminatory policies and abusive behaviors, but part of their institutional embeddedness remains invested, at least in part, in communicating some of these problems and maintaining connections with the international community around human rights. It is important to note that this study maps behavior that occurred, but it does not fully theorize or test why backsliders were motivated to care about and submit derogations. We encourage future research on democratic backsliding and human rights to more fully examine backslider consideration of reputation, foreign policy during backsliding, and specifically international human rights law behavior during backsliding. Research might also track how continued engagement with international human rights law might shape or mitigate backsliding itself. Future research also would benefit the study of whether and how derogations might be used after a crisis has ended. Most states did not formally derogate, but nearly all states implemented similar emergency policies. States that did not rely on derogations implemented emergency policies by stretching domestic norms and laws to accommodate expanded government policies. Do states continue using crisis justification after a local/regional/global crisis is largely over, and does the formality of derogation influence the probability of returning to pre-crisis policies? Newer research hints that derogations were associated with a reduced probability of human rights abuses early in the pandemic and that states that filed derogations did not use temporary measures as a carte blanche “pandemic pass” for additional repression (Chaudhry et al., 2024). However, it is too early to tell if formal emergency declarations will encourage or prevent a return to pre-pandemic policies. Overall, our findings contribute to the understanding of how neither derogation filing nor backsliding alone depict a complete picture of human rights and legal behaviors during the pandemic.

References

Footnotes

The definition of democratic backsliding is contested. Some scholars claim that backsliding can only occur in existing democracies, while others argue that it can happen in any state, regardless of regime type (Little & Meng, 2024). Following other research based on V-Dem’s PanDem data, we take a maximalist definition of backsliding from Waldner & Lust (2018), who argue that “backsliding entails a deterioration of qualities associated with democratic governance, within any regime. In democratic regimes, it is a decline in the quality of democracy; in autocracies, it is a decline in democratic qualities of governance” (2018, p. 95).↩︎