Enforcing Boundaries: China’s Overseas NGO Law and Operational Constraints for Global Civil Society

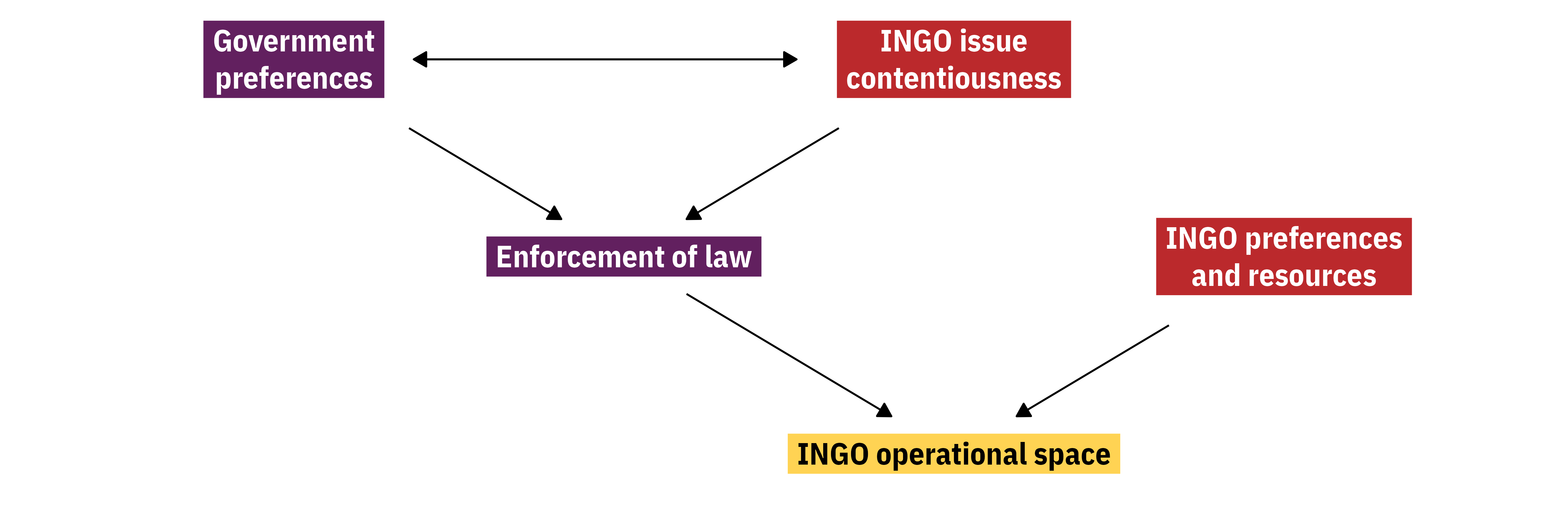

China’s 2016 Overseas NGO (ONGO) Law is part of a larger global trend of increased legal restrictions on international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs). A growing body of research analyzes the broad effects of this crackdown on INGOs, finding a divergence in formal de jure laws and the de facto implementation of those laws. The causes and mechanisms of this divergence remain less explored. Why do authoritarian governments allow—and often collaborate—with some INGOs while harshly regulating or expelling others? What determines the openness of the practical legal operating environment for INGOs? In this paper, we use the case of China to explore how political demands to both restrict and embrace INGOs have shaped the international nonprofit sector in the five years since the ONGO Law came into effect. We argue that in an effort to bolster regime stability, governments use civil society laws as policy tools to influence INGO behavior. We find that INGO issue areas, missions, and pre-existing relationships with local government officials influence the degree of operating space available for INGOs. We test this argument with a mixed methods research design, combining Bayesian analysis of administrative data from all formally registered INGOs with a comparative case study of two environmental INGOs. Our findings offer insights into the practical effects of INGO restrictions and the dynamics of closing civic space worldwide.

international NGOs, civil society, authoritarianism, Chinese ONGO law

The legal framework established by the 2016 ONGO law

International NGOs began to play an important role in China in the early 1990s as part of the country’s Reform and Opening-Up policy, and global civil society has played pivotal roles in providing funding, organizational and program management skills, and catalytic support for China’s emerging domestic nonprofit sector (Yin 2009). Before the 2016 ONGO Law, the regulation of INGOs in China was ambiguous (Shieh 2018; Spires 2022). The only legal document relevant to INGOs was a section of the Regulation on the Management of Foundations, which required that foreign foundations register with the Ministry of Civil Affairs, the regulating agency for domestic nonprofits. However, the actual application of the regulation was very limited: fewer than 30 foreign foundations registered, compared to estimates of over 7,000 INGOs working in China in 2016 (Ye and Huang 2018; Spires 2020). Many INGOs gained legal status by registering as foreign-invested companies (Sidel 2016), allowing them to hire local employees (Holbig and Lang 2022; Yin 2009). However, this legal form is not quite compatible with the non-profit-distributing, social service orientation of civil society (Ye 2021). INGOs registered as foreign-invested companies had to navigate incongruous for-profit regulations, such as rules protecting shareholders’ investment returns.

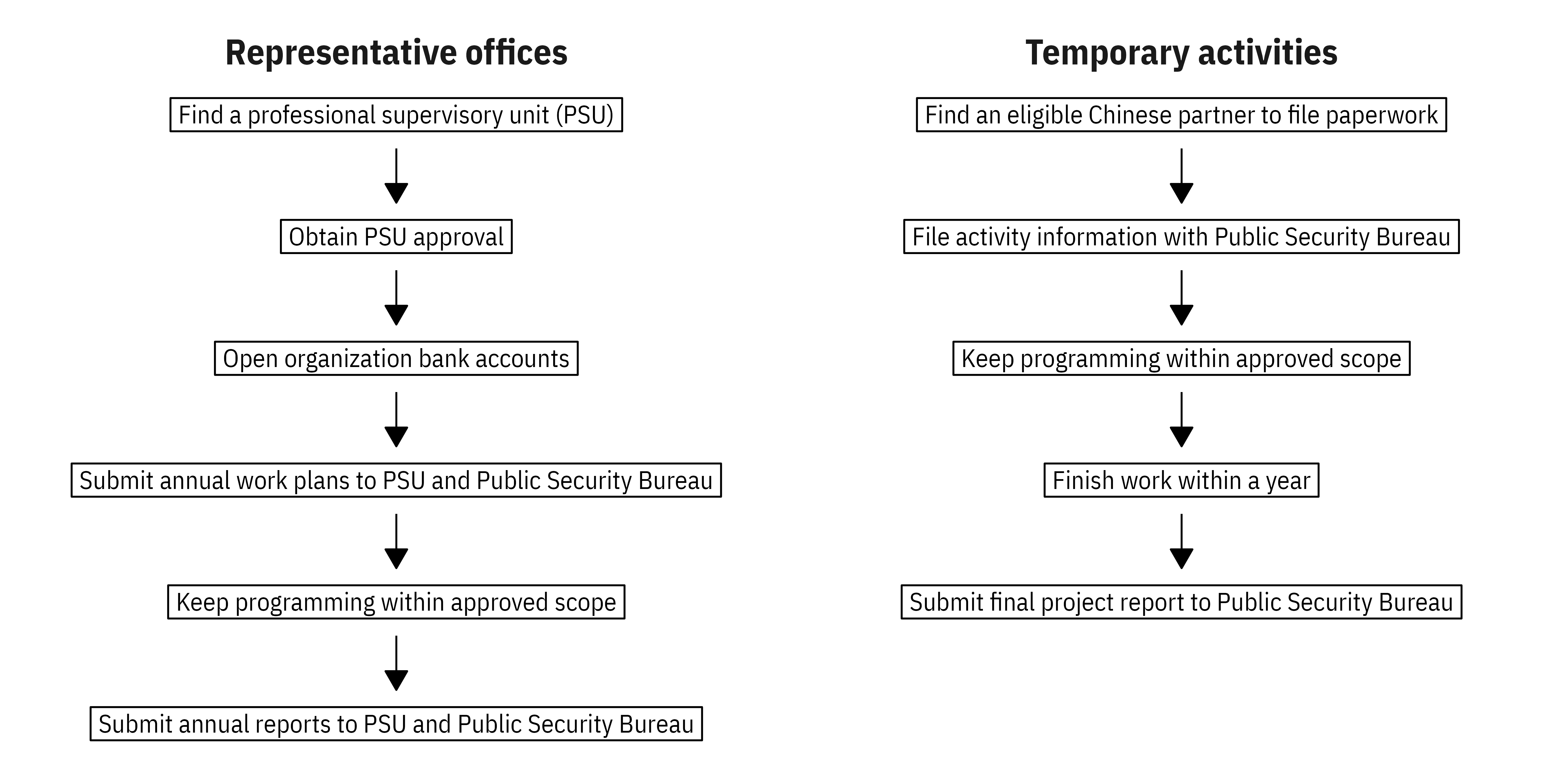

The legal framework governing INGOs was overhauled by the 2016 ONGO Law, which applies to all overseas (including Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan) NGOs that conduct not-for-profit activities in mainland China. The ONGO Law provides two pathways for INGOs to lawfully operate in China (see Figure 1): (1) submitting an application for official status with a representative office (RO), or (2) filing documentation of temporary activities with provincial Public Security Bureaus. Formal registration as an RO allows INGOs to maintain an ongoing presence in the country, while temporary activities are intended for INGOs that need to conduct one-off programs that last no longer than one year. Using one of these two channels to obtain legal status became mandatory in 2017. INGOs are authorized to operate within China on a province-by-province basis. Many organizations are allowed to work in all 32 mainland provincial administrative regions, but many are also only authorized to work in a handful, or even only a single province.

Registering as an RO under the ONGO Law is a complex process that requires the consent of a Chinese Professional Supervisory Unit (PSU)—a governmental or quasi-governmental agency related to an INGO’s issue area that oversees and co-supervises the INGO with provincial Public Security Bureaus. Obtaining the consent of a PSU to apply for registration has become a key challenge for INGOs interested in formal registration, as potential PSUs have no legal obligation to assume such a demanding role (Jia 2017a; Shieh 2018; Ye and Huang 2018). INGOs vary in their ability to attract partner PSUs, and organizations that struggle to find suitable PSUs face limitations in their scope and geographic reach. After successfully gaining legal status, INGOs must follow the law’s operational regulations, such as no fundraising within mainland China, only channeling funds through the RO’s or PSU’s bank accounts, filing reports regularly, and staying within the geographical and issue scopes as approved. INGOs undertaking temporary activities also need to find an eligible Chinese partner—including governmental, quasi-governmental, or non-profit organizations—and must keep their programs within approved limits, but the process is less onerous. According to data from the Chinese Ministry of Public Security and ChinaFile (ChinaFile 2022), between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2021, 593 organizations obtained RO status, while 1,019 organizations submitted documentation for 4,011. Nearly twice as many INGOs have opted for an easier, but far more restricted, pathway for legally operating in China.

Civil society laws in the service of regime stability

The 2016 ONGO Law’s provision of two legal pathways for registration—each with different degrees of freedom—is an example of the broader phenomenon of closing civic space. In the past two decades, authoritarian states have used administrative and legal measures to curtail the influence of global civil society. A rich literature in comparative politics explores how authoritarian regimes counterintuitively use democratic institutions for their own benefit and survival (Kendall-Taylor and Frantz 2014; Gandhi and Przeworski 2007). Authoritarian states hold elections, allow opposition parties in the legislature, and set executive term limits (Meng 2020), but use these democratic-appearing institutions to hedge against possible threats to regime stability. Quasi-democratic institutions are allowed, but only in ways that bolster the government’s stability, and these institutions are kept weak and “dependent on the regime to ensure that they do not develop any real power or autonomy” (Frantz and Ezrow 2011, 7).

Civil society is a democratic political institution that autocrats balance as part of their stability-seeking calculus. Despite the fact that NGOs can act as “agents of democratization” (Toepler et al. 2020), thus posing a threat to non-democratic rule, most authoritarian states permit the growth of domestic and international civil society (DeMattee 2019; Heiss 2019a, 2019b). INGOs provide needed resources and expertise in humanitarian relief, education, and development, and autocrats can rely on these services to consolidate power by providing improved public goods. At the same time, INGOs can pose a threat to stability by exposing human rights abuses, encouraging unwanted political reform, and engaging in political advocacy (Heiss 2019a; Toepler et al. 2020). To capture the benefits and reduce the risk of working with INGOs, most authoritarian states rely on “administrative crackdown” (Chaudhry 2022), or laws that create barriers to NGO advocacy, entry, and funding (Christensen and Weinstein 2013; Chaudhry and Heiss 2022; Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014). These laws, however, are a blunt tool and target civil society as a whole—states do not create one set of formal laws that applies only to regime-friendly INGOs and another set that applies to riskier INGOs. Instead, there is a divergence between the formal de jure laws and the de facto implementation of their accompanying regulations. In practice, NGO laws tend to not be applied universally, and formal laws often serve as a “weapon hanging on the wall that never fires” (Kozenko 2015), acting as a warning to potentially uncooperative NGOs.

The authoritarian benefits of civil society regulations go beyond simply allowing or disallowing specific INGOs. Autocrats engage with INGOs in opposing ways, providing financial support and opportunities for collaboration with those that align with government policy preferences, and using legal mechanisms to restrict or expel those that do not (Toepler et al. 2020; Plantan 2022; H. Li and Farid 2023). The flexible de facto implementation of formal civil society laws allows authoritarians to “use nonprofit regulation as a tool of political control to shore up their continued rule” (Spires 2020, 573), providing them with an additional policy tool for their stability-seeking calculus. These laws allow governments to capture and reshape INGO programming in their favor. Globally, increased civil society restrictions have counterintuitively led to an increase in cooperative, regime-friendly INGO programming, with INGOs praising government policies, engaging in joint programming with the government, and changing longstanding programs to align with government desires (Lian and Murdie 2023).

China’s ONGO law illustrates this dynamic well. The ONGO law requirement to partner with Public Security Bureaus and collaborate with PSUs provides the government with direct influence over INGO decision-making. For example, Oxfam gained RO status in 2017, but only after negotiations with its proposed PSU forced it to stop collaborating with other organizations and local agencies (S. Li 2020). In 2018, INGO programming showed signs of reorienting to be more explicitly aligned with government preferences (Batke and Hang 2018), and by 2021, the issue areas addressed by legally recognized INGOs had clearly “shift[ed] towards fields of activity high up the government’s domestic policy agenda” (Holbig and Lang 2022, 587). Civil society laws thus filter out organizations opposed to the host regime’s policy preferences and grant increased government control over safer and more beneficial INGOs.

Data and methods

We examine these theoretical expectations with a rich dataset of all ROs registered in China between 2017–2021 using Bayesian regression models to understand how the international civil society in China has been reshaped since the implementation of the ONGO law.

Data

Our data comes from INGOs’ public registration documents disclosed by the Ministry of Public Security’s Overseas NGO Office, which maintains a website with complete documentation of all the ROs registered and temporary activities filed across China. We include all RO registrations between January 1, 2017, when the law took effect, to December 31, 2021, with information for all 593 actively registered organizations. The filing documents for ROs disclose each INGO’s name, address, registration date, regulating Public Security Bureau, PSU, issue area and purposes of the RO, and the specific provinces they can work in. We merge this INGO data with translated English organization names from ChinaFile (ChinaFile 2022). Our data and reproducible code are available at ANONYMIZED_DOI_URL.

Measurement and descriptive analysis

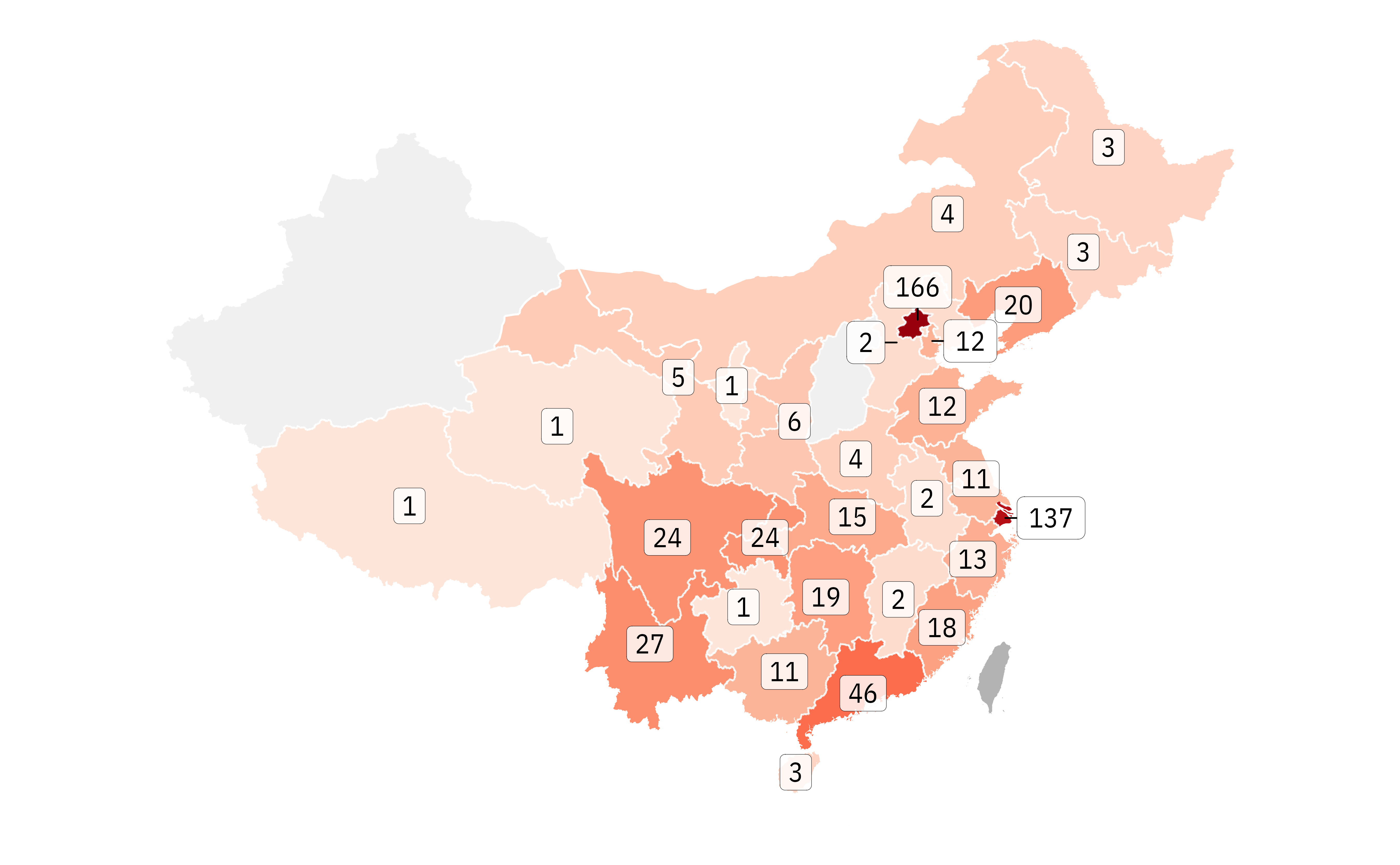

Our dependent variable is the count of provinces that INGOs are authorized to work in. We derive this value from the official registration record, which lists all the provincial regions each INGO RO can conduct activities in. This value ranges from 1–32, the total number of province-level jurisdictions in mainland China. There are clear geographic trends in this measure. Figure 3 shows that Beijing (166), Shanghai (137), and Guangdong Province (46) host the most ROs, while other provinces have as many as 27 and as few as 1 permitted RO.

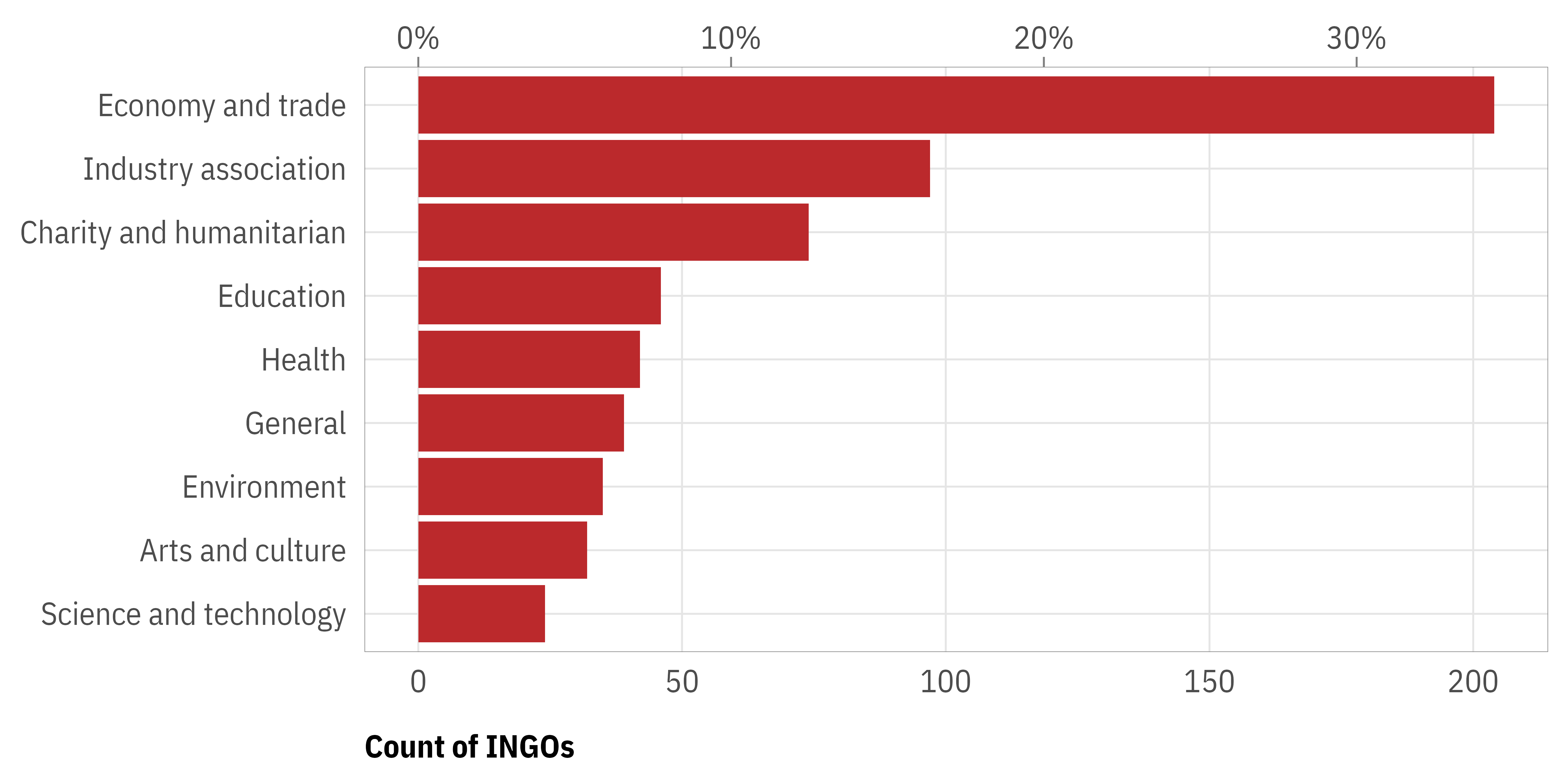

Our key independent variables correspond to each of our three theoretical expectations. First, we code each INGO’s issue area based on its mission statement reported in its registration documentation. Given the subjectivity in the coding process, we cross-checked our manual coding of issue areas (see the appendix for a description of our coding). We use a grounded approach and categorize each organization into nine different issue areas (see Table 1). Figure 4 shows the distribution of these issue areas. The two most common issues are economic, trade, and industry associations, representing 51% (301) of all INGOs. Many of these organizations are bilateral chambers of commerce or other multilateral trade organizations. Charitable, humanitarian, education, and health INGOs are far less common than their trade and industry counterparts: charity and humanitarian organizations comprise 12% (74) of ROs.

The composition of INGOs successfully got registered under the ONGO law shows that the populations of INGOs that are allowed a long-standing legal presence are predominantly trade and economic organisations and industry associations, or non-civil-society organizations.

| Issue | Examples |

|---|---|

| 1 Includes poverty alleviation, disaster relief, rural development, etc. | |

| 2 Includes grant-making organizations, organizations working on general international communication, and organizations working on multiple non-overlapping issues | |

| Arts and culture | World Dance Council; Special Olympics |

| Charity and humanitarian1 | Save the Children; World Vision |

| Economy and trade | World Economic Forum; Canada China Business Council |

| Education | Children's Education Foundation; BSK International |

| Environment | The Nature Conservancy; World Wide Fund for Nature |

| General 2 | Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; Ford Foundation |

| Health | American Heart Association; Operation Smile |

| Industry association | World Cement Association; Colombian Coffee Growers Federation |

| Science and technology | Royal Aeronautical Society; American Society of Civil Engineers |

Our second independent variable is a dichotomous indicator of whether the INGO explicitly states that it intends to operate locally or sub-provincially. There are cases where the aim of the INGO is attached to a locality, either having a county or city name in their RO name or purposes, or the INGO is actually set up by people in China who registered the RO to communicate between the “hometown” and the INGO set up abroad. Of the 593 ROs, 77 (13%) have a narrow local focus.

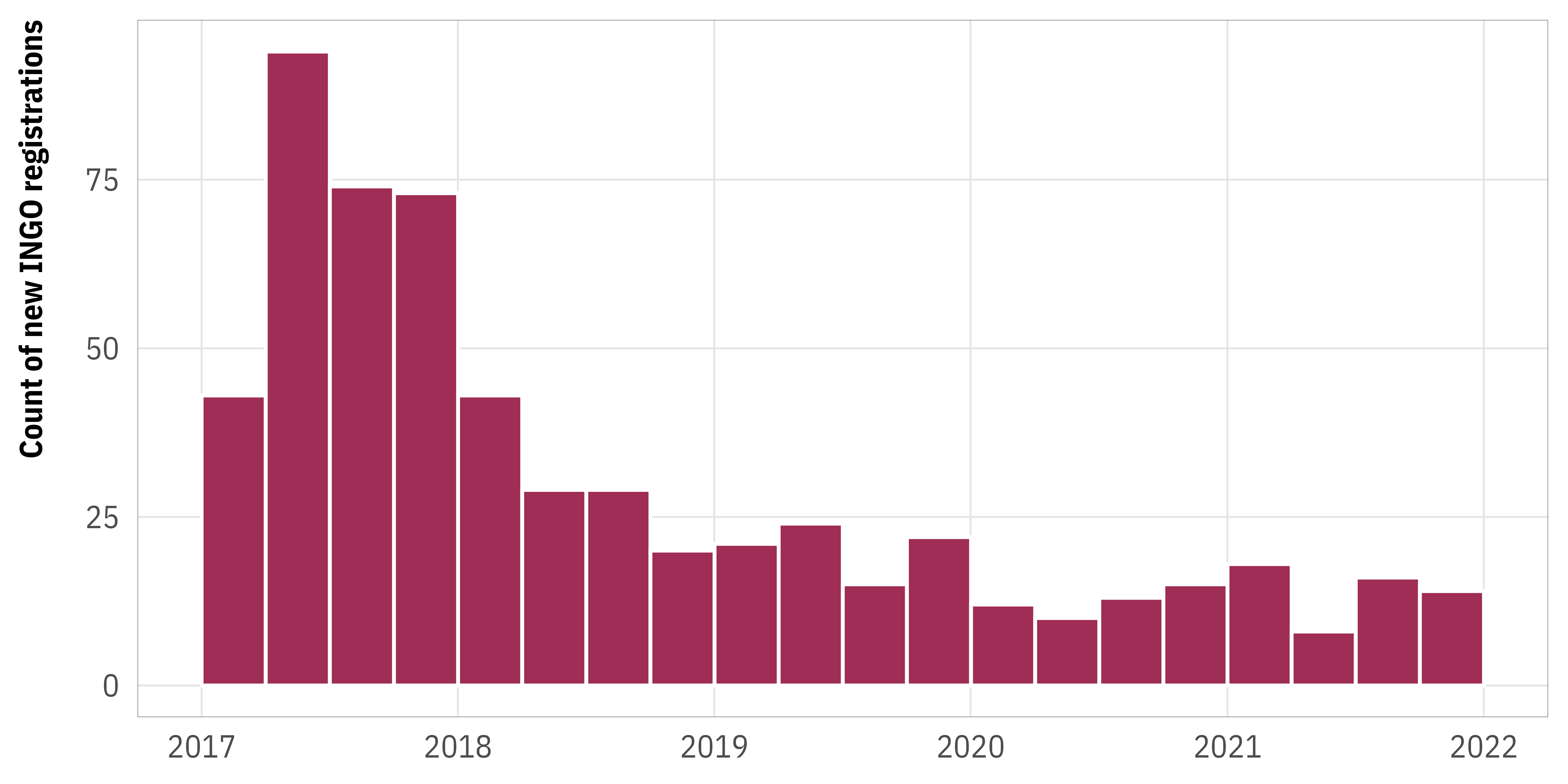

Our final independent variable measures how much time elapsed between January 1, 2017 and the organization’s official registration date. There is great variance in registration timing, since there was a brief grace period for INGOs to seek legal presence after the law took effect (Shieh 2018). Nearly half of all ROs—48%—registered in 2017, and the count of new registrations gradually declined after the initial first-year wave (see Figure 5). This is largely because both INGOs and regulators needed transitional time to explore the specific application of the law during the ambiguous first few months. We use this temporal variable as a proxy for the motivation or eagerness of INGOs to register as an RO, since INGOs may have been inclined to avoid the cumbersome registration procedures at the early stage if there were no real consequences for delaying, while others took the time to talk with multiple potential PSUs to find a more suitable superior or regulatory dynamic (Jia 2017b).

Modeling approach

(To do - Andrew: update the paragraph below with more explanations/justifications? ) We use a multilevel Bayesian regression model to examine the complex effects that issue area, local connections, and registration timing have on organizational flexibility. This approach allows us to hold specific variables constant and generate predictions for hypothetical new, not-yet-registered INGOs, providing us with stronger empirical implications. Additionally, Bayesian modeling allows us to analyze the uncertainty associated with INGO operational space—instead of reporting a single value for the number of provinces INGOs have access to, we report posterior credible intervals that represent the probability that the average geographic reach falls within a specific range.

We are not interested in statistical significance or hypothesis testing. (Meng’s note. Starting with the negative sentence may be too blunt. Suggest to change the order of Sentence 1 and Sentence 2). Instead, we are interested in the overall registration patterns across our three expectations. Accordingly, while we report full model coefficients, care should be taken to not be concerned if those coefficients are statistically different from zero, or if coefficients for one issue area are statistically different from another issue area. Instead, we use these model results to generate posterior predictions that illustrate the full range of possible registration patterns.

This is also apparent in our graphical results. Rather than display coefficients that demonstrate the marginal effects of one issue area compared to another, we provide posterior predictions of the expected counts and proportions of authorized provinces. The model results are thus descriptive explorations of our expectations, not confirmatory hypothesis tests.

Additionally, we introduced province fixed effects in the model to account for socio-economic or institutional differences across provinces, as well as registration year fixed effects to account for any potential administrative processing variance during COVID years.

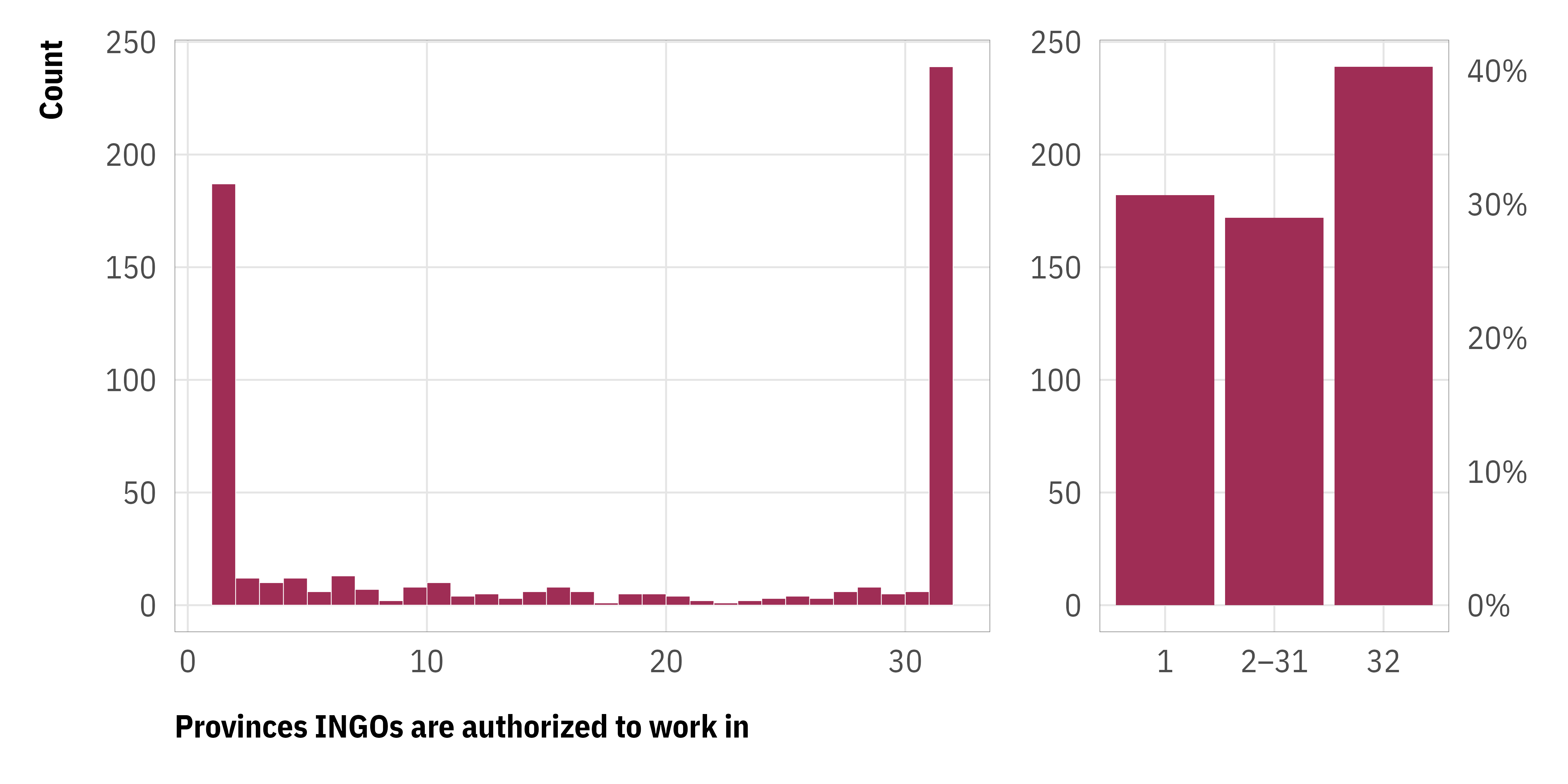

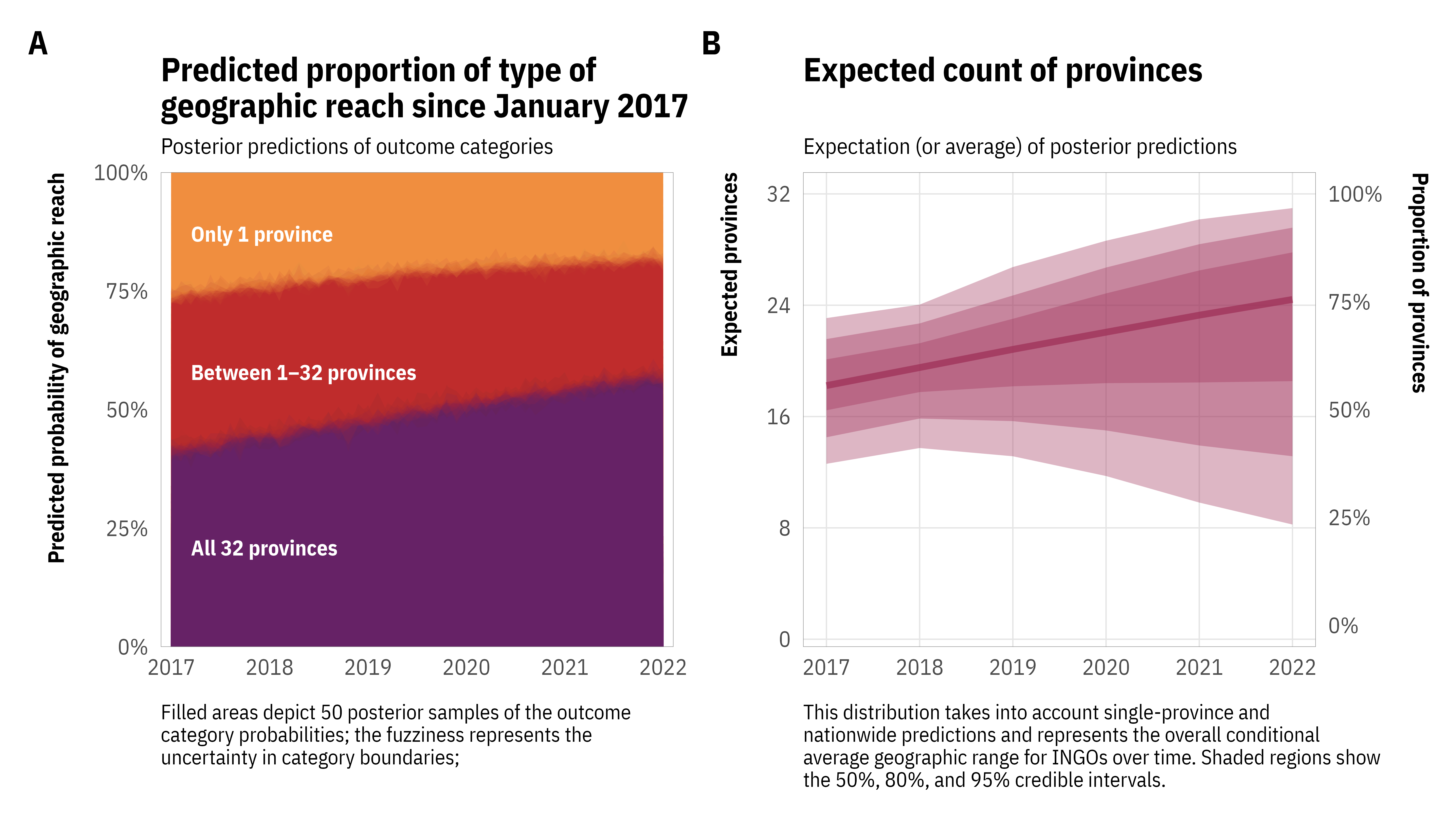

Modeling the count of provinces each INGO is authorized to operate in presents a unique statistical challenge. As seen in Figure 6, roughly 30% of INGOs are registered in only one province, 40% are registered nationwide, while the remaining 30% are registered in 2–31 provinces. Our main variable of interest is thus a mix of continuous outcomes (i.e. a range of provinces) bounded between two discrete outcomes (i.e. one province and all provinces). Standard modeling approaches like ordinary least squares regression (OLS) cannot accurately capture the unique features of the data and will generate predictions that fall outside allowable bounds (i.e. negative counts of provinces or more than 32 provinces). To account for values at the bounds, we rely on ordered Beta regression (Kubinec 2022), an extension of zero-and-one-inflated Beta regression that allows us to simultaneously model the continuous range of provinces (2–31) and the discrete outcomes (1 province and 32 provinces). We can thus explore the dynamics of each of our independent variables of interest in multiple ways—we can see how each variable (1) predicts that an organization works in one province, nationwide, or somewhere in between, and (2) predicts the overall expected count of provinces.

Since we are primarily interested in the influence of INGO’s issue area, its local connections, and the timing of its registration on its operational space, we include these as explanatory variables. We also include random province intercepts to account for between-region differences in how INGOs are regulated, since every RO is overseen by provincial-level Public Security Bureaus. The appendix contains complete details of our modeling approach, priors, model definition, and tables of raw results.

To discuss this whole paragraph and add model formulas back

Results and discussion

Model results

add the discussion of “significance level, or the interpretation of credible intervals. That is move some of the notes to the figure to the main text?” - explain credible intervals and how it shows us the whole distribution and is more actionable than confidence intervals and trying to get a single parameter. The point of this whole model is to paint a broad picture of the whole situation.

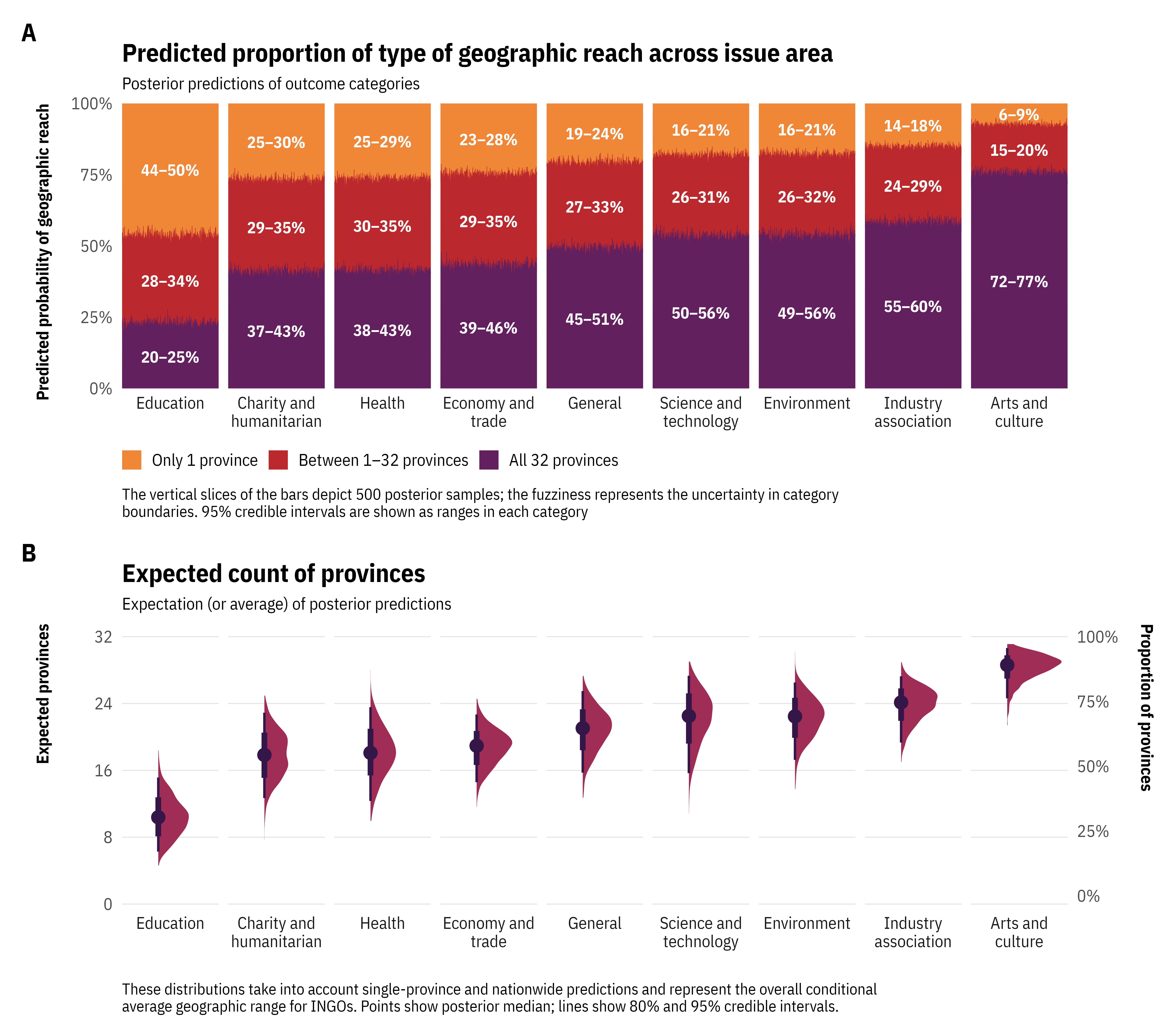

Issue area

Next, we explore the data in more depth by generating and analyzing posterior predictions from our model. Following our first theoretical expectation, we predict that INGOs working on less contentious issues should be registered in more provinces and thus have more geographic flexibility. We take advantage of the simultaneous continuous and discrete features of ordered Beta regression to see how often an INGO in each issue area is predicted to work in a single province, across all provinces, or some number in between. Figure 7(a) presents a summary of predicted posterior outcomes for 1,000 hypothetical INGOs, varying each issue area and holding all other variables at their mean or modal values.

Several notable trends emerge from the model results. INGOs focused on arts and culture are overwhelmingly the most likely kind of organization to work nationally—arts and culture organizations are predicted to work in all 32 provinces 72–77% of the time and are only predicted to work in a single province a rare 6–9% of the time. Education-focused INGOs, on the other hand, are the least likely kind of organization to be registered in all 32 provinces and are predicted to do so only 20–25% of the time. Education INGOs are the most likely to be registered in only one province, with that predicted outcome appearing 44–50% of the time, 15–20 percentage points higher than any other issue area’s predicted proportion. All other issue areas follow roughly similar patterns in predictions: the most common outcome is for organizations to work nationally (≈45–60% of the time), followed by working in at least 2 provinces (≈25–35% of the time), followed by working in a single province (≈15–30% of the time). Figure 7(b) shows the continuous posterior distribution of the average number of provinces INGOs are expected to be registered in across all types of issue areas, but accounting for the 1- and 32-only provinces simultaneously. We can see a similar trend—arts and culture INGOs are predicted to work in 25–31 provinces on average, while education INGOs are only predicted to work in 6–15. All other issues range between 15–25 provinces.

As explained previously, we expect that the contentiousness of an NGO’s issue area should influence its geographic reach and overall flexibility. No INGOs engaged in contentious issues like human rights advocacy have successfully registered in China, but there is some slight variation in the level of contention even among organizations working on less contentious issues like humanitarian assistance, health, and the environment. Education is particularly notable as the least flexible and most geographically restricted subsector. While education is typically considered a low-contention issue, fears of Western influence through educational institutions were an original impetus for China’s ONGO law. In 2006, an article in a CCP-owned newspaper warned that the growing presence of international NGOs would “undermine national security,” “destroy political stability,” “foster corruption,” “propagate foreign practices,” and “spy on and gather information on China’s military, political, and economic information” (Yin 2009, 534). The idea that INGOs would “propagate foreign practices” had especially powerful salience, since increased exposure to the West through international NGOs had the potential to “lead to adoption of Western ideas of liberty, further endangering government control over the populace” (Hsia and White 2002, 337). Educational NGOs were one particular avenue for the West to exert influence in the country—the directors and presidents of dozens of China’s largest domestic NGOs have received doctoral degrees from and hold visiting appointments at Cornell, Duke, UNC-Chapel Hill, Harvard, Yale, and other prominent US universities (Wang 2012, 108–9), and their training and connections abroad have influenced their programming and advocacy at home. In 2006, one Chinese NGO leader candidly explained that “foreign influence is definitely great. There is conceptual influence. Foreign NGOs’ working methods also affect Chinese NGOs” (Wang 2012, 110). Education is therefore one of the more contentious issues allowed under the ONGO law, and is thus more closely regulated and restricted.

The officially-endorsed environmental issue area in China is also less contentious. Take the The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and Greenpeace for example. They both well-known environmental INGOs with headquarters in Western countries. They each began working in China around the turn of the century, with TNC establishing an office in Beijing in 1998 and Greenpeace in 2001. However, one key difference in these two organizations is their working model and alignment with government preferences. TNC has stated that its work is “science-based” and that the organization uses a “non-confrontational, collaborative approach in working closely with governments, the business community and others” (China Philanthropy Research Institute 2018b).In contrast, Greenpeace engages in direct advocacy, using peaceful—but confrontational—protests to expose environmental abuses and shame governments and for-profit corporations that harm the environment. The organization describes its work in China with phrases like “non-violent direct action,” “impartiality and independence,” and “brings change,” indicating its dedication to maintaining organizational independence as it acts as an environmental watchdog (Greenpeace 2023). Being the more contentious type of environment results in a contrasting fate for the Greenpeace from TNC. TNC obtained RO status in May 2017, partnering with the National Forestry and Grassland Administration as their PSU, and receiving authorization to work in 27 provinces. In contrast, Greenpeace has not received RO status and has instead filed 67 temporary activities, submitting new documentation more than ten times each year. Not only this means much limited operational space - only in the location of the activity - but also higher level of uncertainty and administrative costs. (Plantan 2022) also found environmental organizations in China “increasingly align with central party-state priorities on environmental protection” and are intended to help bolster political stability. So the successfully registered environmental organizations are less contentious in China.

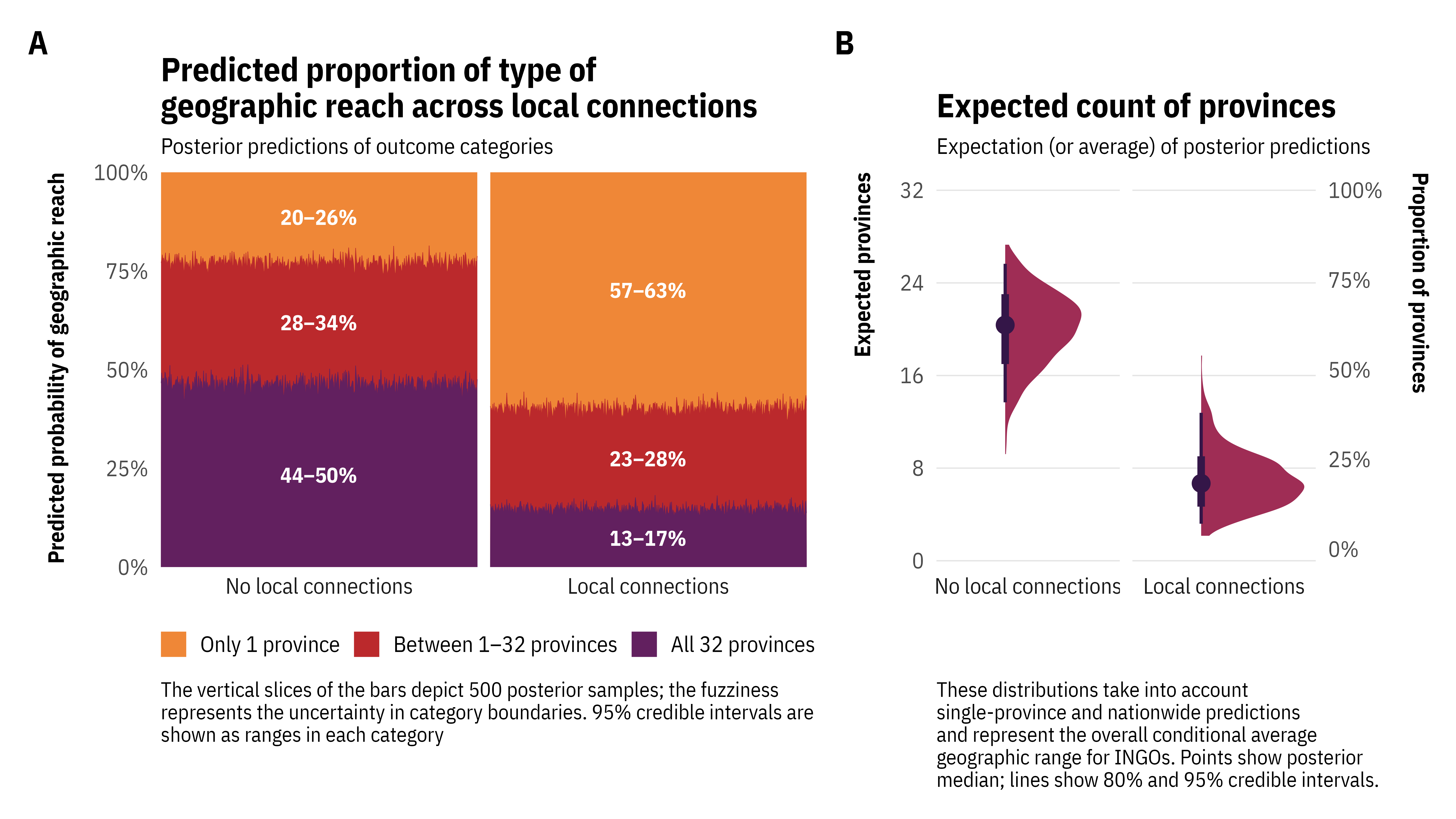

Local connections

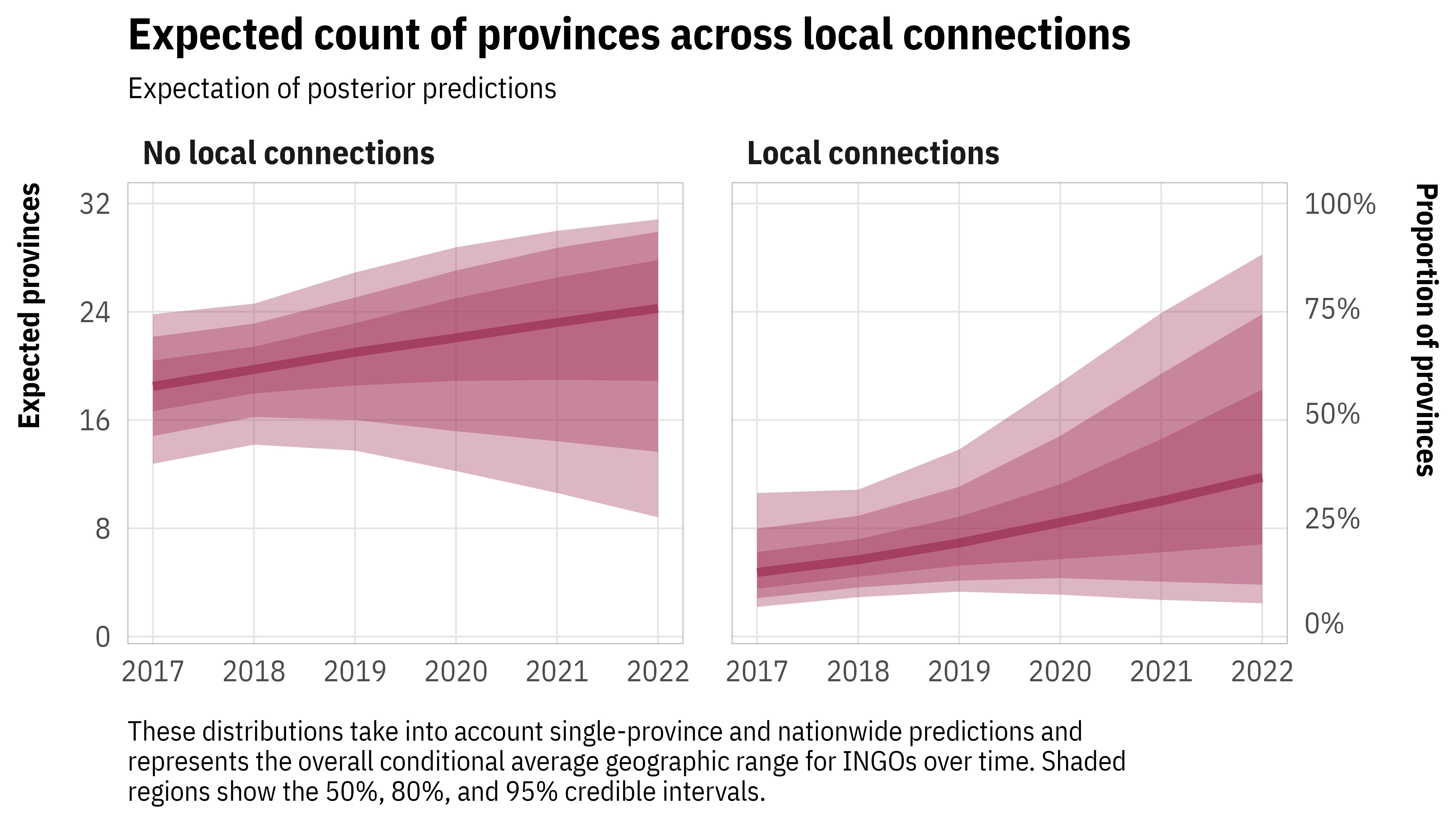

In our second theoretical expectation, we posit that INGOs with an explicitly local focus should be registered in fewer provinces. The results from our model confirm this expectation. Figure 8(a) shows that organizations without local connections are predicted to work nationally across all provinces nearly half of the time (with a 95% credible interval of 44–50%), with a 28–34% probability of working in two or more provinces. INGOs without local connections only have a 20–26% probability of working in a single province. In contrast, INGOs with local connections are far more likely to only work in one province (57–63%), or only work in a handful of provinces (23–28%). For these locally-focused organizations, the least common prediction is to work nationally, with only a 13–17% probability. Figure 8(b) shows the posterior distribution of the average number of provinces INGOs are expected to be registered in, conditional on their local connections. The same relationship holds—an INGO without local connections is predicted to work in 14–26 provinces on average, while an organization with local connections is only predicted to work in 3–13.

INGOs with locally focused missions and connections with provincial officials are thus far more likely to purposely limit their activities to specific provinces, while organizations with broader missions have a larger geographic reach. While we cannot precisely tell which direction the causal story works with this phenomenon, we can make some reasonable speculations. It is likely that locally-oriented INGOs purposely network and seek out connections with local PSUs before formally registering, thus fostering better relationships with government officials and furthering the organization’s mission within its limited provinces. It is also likely, given the high probability of national reach, that organizations without local connections purposely do not spend the time and effort to cultivate those relationships, as it is not necessary to operate across many provinces. A rival explanation that having local connections reduces an organization’s operational space does not seem warranted—although INGOs with local connections do have a more limited geographic scope, organizations appear to purposely limit the number of provinces they work in in order to focus more on their local work.

Registration timing

In our third theoretical expectation, we propose that early registrants were both less of a threat to regime stability and a higher priority for bureaucratic processing and thus should be registered in more provinces. However, the results of our model support the opposite of this expectation. In Figure 9(a) organizations that registered in the first year have a 39–44% probability of working in all provinces and a 30–35% probability of working in two or more provinces. These early INGOs are the most likely to be registered in only one province and are predicted to do so 24–29% of the time. After 2017, the likelihood of nationwide reach steadily increases and replaces both the probability of a single province or a partial range of provinces. By the end of 2021 the probability of national-level registration increases to 54–59% while the probability of working in a range of provinces increases to predicted to work in two or more provinces remains around 22–27%. These later INGOs are the least likely to 8be registered in only one province, with a probability of 17–21%. Figure 9(b) demonstrates the expected count of provinces over five years since 2017. INGOs that register early are predicted to work in 13–23 provinces on average, while those that wait until 2021 are predicted to work in a far more uncertain 8–31.

To do: update the discussion according to the new Expectation 3

We lack sufficient theory to explain why this trend goes against our expectations, but we can again make reasonable speculations. As we saw previously with INGOs and local connections, organizations appear to strategically seek out the best avenues for registering (Jia 2017b). Organizations that participated in the initial wave of registrations in 2017 likely had closer connections with local officials and were able to speed through the bureaucratic process registration more easily. As a preliminary test of this speculation, we rerun our main model with an interaction between years since registration and local connections to see how the effect of local connections changes over time. As seen in Figure 10, early registrants in 2017 without local connections are more likely to have a larger geographic reach, registering in an average of 13–24 provinces, while their locally-focused counterparts are only expected to register in an average of 2–11 provinces. Accordingly, it may be that INGOs with local connections are more likely to register early because of their pre-existing bureaucratic relationships, while organizations with a larger national reach take longer to undertake the registration process and thus register later. Another possible explanation could be that earlier registration signals greater eagerness to reduce the uncertainty surrounding organizational legal status. INGOs that perceive themselves as more contentious may be more nervous about the legal consequences of not being able to register and thus be more willing to seek registration earlier (China Philanthropy Research Institute 2018a). Compared with their safer, less contentious peers, INGOs seeking to register earlier are more likely to have reduced operational space. To understand the underlying mechanism with registration timing, further research is warranted.

Conclusion

Political institutions are central to authoritarian stability as autocrats work to co-opt and balance institutional challenges to their regime. Autocrats treat civil society—both domestic and international—as yet another actor in their stability-seeking calculus. The ongoing phenomenon of closing civic space, where governments worldwide continue to impose repressive regulations on civil society, can be seen as a strategy for stabilizing authoritarian rule (DeMattee 2019; Carothers and Brechenmacher 2014; Heiss 2019a). Notably, these laws are not enforced universally or consistently. The strategic enforcement of civil society laws creates a divergence between formal de jure regulations and the de facto implementation of those laws. Formal laws provide a legal framework for regulating INGOs, but government flexibility in enforcing those laws allows regimes to (1) act leniently towards organizations that offer services and expertise that benefit the regime, and (2) restrict, repress, or expel organizations that are deemed a risk to regime stability.

We argue that regime preferences interact with organizations’ issue areas to create variation in INGO operational space, or the de facto regulatory environment afforded to INGOs. We explore this theory by analyzing a novel dataset of all INGOs that have successfully registered in China since the implementation of the 2016 ONGO Law, a legal mechanism that provided the government with the ability to grow and shrink INGO operational space in strategic ways. By focusing on a specific law in one country, our work provides rich empirical illustrations of the mechanics of authoritarian administrative crackdown. We find that INGOs that work on issues that are less threatening and more aligned with regime preferences—such as arts & culture INGOs, industry associations, and scientific organizations—are registered in more provinces and thus enjoy a greater degree of operational space, while organizations that pose a potential threat—like education INGOs—are far more limited geographically. Our case study finds similar results. Because of its less confrontational approach and its connections to local government officials, The Nature Conservancy was able to obtain RO status and benefit from increased operational space while the more advocacy-focused Greenpeace has resorted to filing dozens of program-specific temporary activities.

Studying INGOs in authoritarian regimes poses a number of limitations, but the concept of operational space can address some of these issues in the future. The results from our model provide useful insight into the operational space of INGOs that have been able to formally register. These organizations have been pre-screened and deemed to be safe and non-contentious. This can help explain why some seemingly more contentious issue areas such as environmental INGOs enjoy relatively more operational space (see Figure 7). Since Chinese authorities can benefit politically from the work of environmental INGOs, they “selectively encourage low risk groups and selectively channel higher risk groups into permitted areas” (Plantan 2022, 504). But given the focus of this paper on registered ROs, we cannot make comparisons with INGOs that left the country prior to 2017 or INGOs that have explicitly chosen to not work in China. This is not an issue specific to China—analyzing the international nonprofit sector of any country that has passed similar laws will raise similar issues of selection bias. The Chinese context provides one possible way forward: future research can further explore the relationship between INGOs and regime preferences by comparing characteristics of INGOs that register as ROs or undertake temporary activities using already-available administrative data. Second, this paper focuses exclusively on INGO regulations in China, and the specific legal mechanisms for controlling INGOs in other countries will naturally differ. However, the findings are still instructive. We have illustrated how the implementation of one INGO law has reshaped the role of international civil society, leading to a preponderance of regime-friendly NGOs, many of which have realigned their programming with government preferences. It is likely that a similar dynamic plays out in other countries—regimes legislate civil society broadly and enforce those laws specifically. Future research might analyze the determinants of INGO operational space in other authoritarian states, which can help INGOs facing legal crackdown abroad strengthen their organizational flexibility in the face of legal restrictions.

References

Footnotes

“Civil society” is a broad concept that includes a range of organizational forms, both formal and informal. In this paper, we look at nonprofit organizations or third sector organizations—formal non-profit-seeking organizations that are neither privately-owned nor government-controlled. We define international NGOs as organizations that work predominantly in at least one other country outside of their home country.↩︎