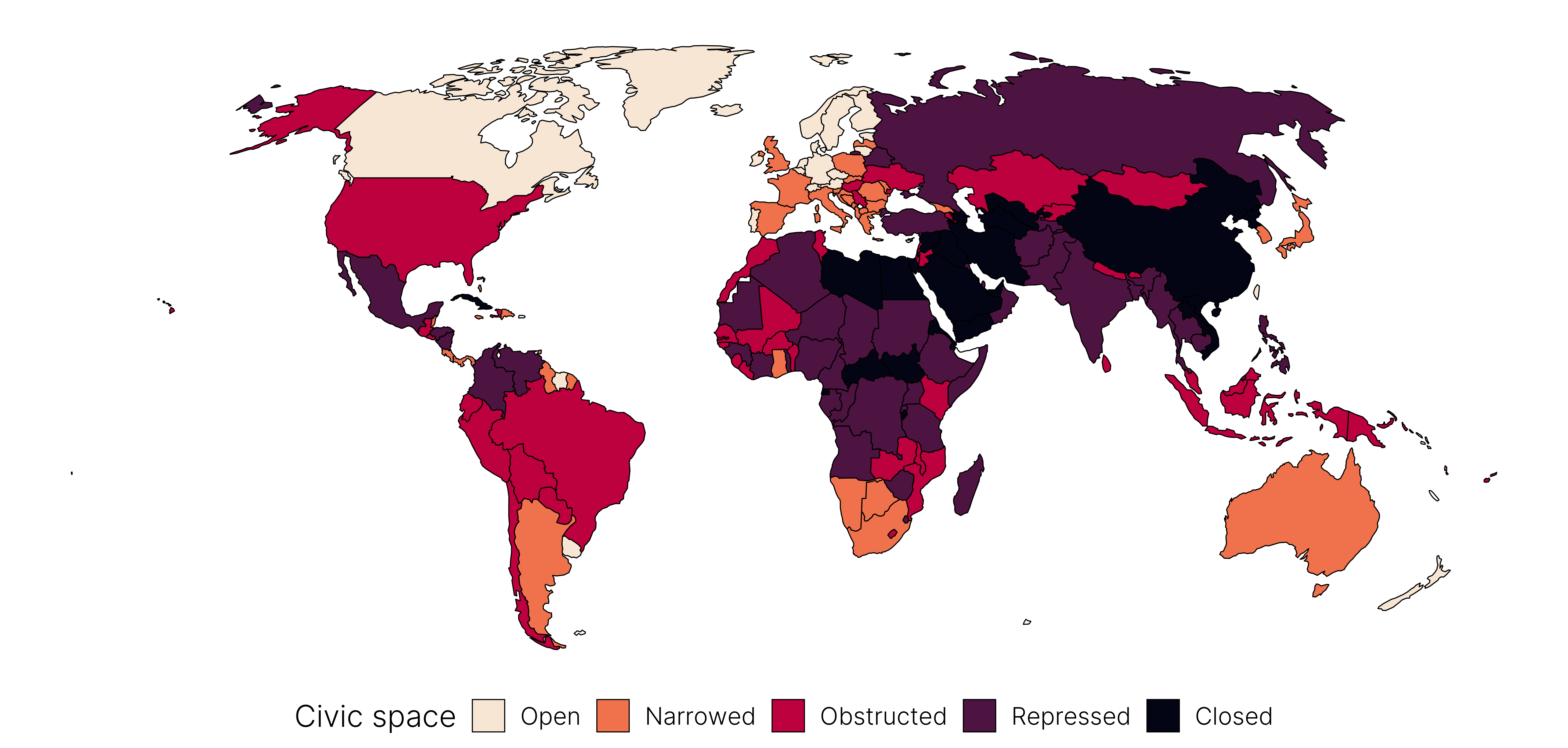

Over the last few decades, governments across the globe have been increasingly cracking down on civil society organizations (CSOs), particularly non-governmental organizations (NGOs)—a phenomenon commonly known as closing or shrinking civic space (Carothers & Brechenmacher, 2014; Chaudhry, 2016; Dupuy et al., 2016; Dupuy & Prakash, 2018). More than 100 countries have proposed or enacted 244 different measures that have restricted, repressed, or shut down civil society since 2013 (International Center for Not-For-Profit Law, 2021). In Human Rights Watch’s 2016 World Report, Executive Director Kenneth Roth argued that civil society was under more aggressive attack than at any time in recent memory. As seen in Figure 1, by the end of 2020, only 21% of countries had open and unrestricted civic space (Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021; CIVICUS, 2021).1

Figure 1: 2020 CIVICUS Monitor civic space ratings

This hostility to civil society is not unique to autocratic governments or even illiberal democracies (Abramowitz & Schenkkan, 2018)—long-established liberal democracies have also increased restrictions on civil society in their countries. Over the past decade, India has canceled the licenses of tens of thousands of NGOs, targeted major groups such as Greenpeace International, Amnesty International and Ford Foundation, and has banned thousands of NGOs from receiving foreign funds (Press Trust of India, 2015, 2019). In 2013 Canada attempted to revoke the charitable status of NGOs for opposing the Northern Gateway pipeline and Canadian mining companies’ initiatives abroad (CIVICUS, 2013). In 2019, activists from the US-based nonprofit No More Deaths were arrested for providing food and water to migrants at the US-Mexico border and faced a 20-year prison sentence before their convictions were overturned in 2020 (Cramer, 2020).

Much of this targeting of NGOs has been non-violent. Rather than publicly arrest or beat activists, states implement “administrative crackdown,” or the passage of anti-NGO laws to create barriers to NGO advocacy, entry, and funding (Chaudhry, 2022).2 The use of legal tools instead of violent repression means that NGOs have to adapt their practices to stay within the bounds of permitted activities and operations (Heiss, 2017, 2019). While this can lead to the depoliticization and avoidance of direct political activism by CSOs (Bloodgood & Tremblay-Boire, 2017), states cannot soften or neutralize all forms of political activity and advocacy in subtle, legal ways like they have with NGOs. Sooner or later, states may need to deal with threats to their stability in a more direct, violent, confrontational manner. Anti-NGO laws could be an important early warning sign—or a canary in the coal mine—of worsening human rights repression, signaling that a state will continue down the path of further repression. What does state targeting of NGOs tell us about the state’s broader respect for civil society and the overall level of human rights repression? Can the crackdown on NGOs act as a predictor of subsequent increasing repression?

In this paper, we explore the power of anti-NGO repression in predicting political terror and broader patterns of human rights abuses. We argue that information about NGO crackdown can be a valuable indicator of human rights trajectories. It can act as an early warning signal for worsening repression, suggesting which countries are testing the waters with comparatively “milder” methods of crackdown before enacting more violent forms of repression. To assess if attacks on NGOs and activists can provide us useful information about future repression, we use an original dataset on state crackdown on NGOs using anti-NGO laws across all countries from 1990–2013. We differentiate between two forms of NGO repression: de jure anti-NGO laws, and their de facto implementation. While the former captures anti-NGO laws that seek to repress these organizations, the latter captures their effects when they are actually implemented or enforced. The distinction is important—laws may frequently be passed to create a chilling effect on civil society. They provide a legal threat that could compel NGOs to self-censor, without actually seeing any uniform or widespread implementation.

Using multilevel Bayesian modeling, we find that formal de jure laws provide a weak signal of future repression. Increasing de facto civil society repression, on the other hand, predicts both a moderate increase in the probability of moderate political terror and a deterioration in the overall respect for human rights in a typical country.

Our paper makes two important contributions to the fields of repression and international human rights law. First, in predicting the onset of repressive state policies, while structural factors such as levels of democracy, economic development, electoral competitiveness can identify countries that are likely to have more or less respect for civic freedoms, these factors are also slow to change over time. As such, they may not be particularly suitable for forecasting short-term trajectories, especially for moderately repressive countries. On the other hand, state repression of NGOs is a more dynamic process that may provide insight into changing levels of human rights standards and repression in subsequent years. While recent research has made important contributions to studying the extent and effects of state crackdown on NGOs, much of this focuses on de jure restrictions and its impact on NGOs and donors (Bakke et al., 2020; Bromley et al., 2020; Christensen & Weinstein, 2013; Dupuy et al., 2016; Dupuy & Prakash, 2018; Smidt et al., 2021). By looking at laws and their actual practices of implementation, we are able to assess the long-term effects of closing civic space on broader patterns of repression.

Second, by examining the growth in anti-NGO laws and their effects on patterns of human rights abuses, our results also have important implications for understanding the future of human rights legislation. Existing research on international human rights law shows that civil society groups play an important role in highlighting states’ violations of their treaty commitments. By revealing the gap between treaty provisions and actual state behavior, these organizations play a vital role in reducing the “compliance gap” between legal commitments and state practices (Hafner-Burton & Tsutsui, 2005; Hathaway, 2002; Simmons, 2009). The dramatic rise in anti-NGO laws and their implementation through de facto civil society repression threatens to exacerbate this compliance gap. Indeed, recent research finds that when governments have committed to human rights treaties and continue to commit severe human rights abuses, they impose anti-NGO laws to escape monitoring (Bakke et al., 2020). Our findings support these arguments by showing that de facto levels of NGO repression are a possible predictor of broader patterns of human rights violations.

Below, we first look at existing literature on repression and political violence, outlining state motivations to repress NGOs. We then elaborate on why attacking NGOs may be an important predictor of subsequent repression. Using both original data as well as data from several existing datasets, we build an ensemble of predictive models and explore (1) the marginal effects of civil society repression on different forms of broader human rights repression, and (2) the out-of-sample predictive performance of each model. We then illustrate one of the mechanisms of our findings—the distinct impact of de jure and de facto anti-NGO repression—with a brief case illustration of Egypt’s treatment of civil society since 2002. We conclude by discussing the implications of our findings on autocratic survival, and how states may manage NGOs as a strategy to remain in power.

Government repression and NGO restrictions

Repression is the use of coercive action against an individual or organization, for the purpose of imposing a cost on the target as well as deterring specific activities perceived to be challenging to government personnel, practices, or institutions (Davenport, 2007a, p. 487; Goldstein, 1978, p. xxvii; and Conrad & Ritter, 2019, p. 15). Early literature on repression focused on the role of structural factors such as levels of democracy, economic development, and electoral competitiveness in predisposing a state to the increased use of repression. Most notably, democratic forms of government—and democratization in general—has a pacifying effect on state repression (Davenport & Armstrong, 2004; Krain, 1997; Richards, 1999). Democracies have a negative effect on repression largely because of the increased probability of sanctions against authorities for undesirable behavior (Davenport, 2007b, p. 47).

More recent research focuses on how the behavior of various actors shapes government response. One of the most consistent findings in the political violence literature is that authorities repress to counter ongoing challenges to the status quo. In other words, dissent increases repressive behavior (Davenport, 2007a). However, dissent and repression have an endogenous relationship: state authorities frequently engage in preventive repression to undermine or restrict groups’ abilities to dissent (Conrad & Ritter, 2019; Ritter & Conrad, 2016). NGOs are one actor that can pose challenges to political authorities, and state repression of these actors—especially through anti-NGO laws—can be considered a form of preventive repression (Chaudhry, 2022).

This preventive repression of NGOs is a recent phenomenon. While many saw the initial proliferation of NGOs in the 1980s and 1990s as leading to a “symbiotic relationship” between NGOs and states due to their mutual goals, this perception changed over time (Reimann, 2006, p. 63). With expanded powers and their perceived role in the Color Revolutions, NGOs began to be seen as having a real influence on both domestic and international politics (Carothers & Brechenmacher, 2014). State perception of NGOs as threatening became pervasive as these organizations demonstrated their ability to influence electoral politics (Dupuy et al., 2016; Weiss, 2009), mobilize aid (Bell et al., 2014; Boulding, 2014; Murdie & Bhasin, 2011), and threaten a state’s economic interests (Dietrich & Murdie, 2017; Lebovic & Voeten, 2009; Nielsen, 2013).

Given this threat, a number of states decided to repress threatening NGOs. While violence is often effective at curbing dissent, it can also backfire, leading to widespread protests, decreasing leaders’ legitimacy and increasing their criminal liability (Kim & Sikkink, 2010; Sikkink, 2011). In contrast to violence, anti-NGO laws have fewer adverse consequences—citizens may see it as regulation rather than repression. It may also circumvent concerns among state security or bureaucratic agents about illegitimate orders based on violent repression (Stephan & Chenoweth, 2008). There are also fewer international consequences since laws—unlike violence—rarely invite condemnation or threats of aid withdrawal (Carothers & Brechenmacher, 2014).

These anti-NGO laws can provide convenient avenues for more violent repression and can foreshadow future government transgressions. Autocratic leaders want to avoid accountability and NGOs often stand in conflict with that goal. Civil society organizations, including NGOs, can help shape the narrative of leaders’ performance both domestically and internationally. Monitoring by NGOs and subsequent shaming can include significant external revenue loss to states in the form of loss of aid, trade, and foreign direct investments (Barry et al., 2013; Keck & Sikkink, 1998). Government attempts to repress NGOs through the use of law can signal the beginning of a deteriorating human rights situation. Such repression reflects the government’s willingness and capability to use measures that can make it avoid accountability. Once a state targets NGOs, over time it may grow less hesitant to apply violent repression more widely and more severely, thus leading to broader contractions of civil and human rights throughout the country.

In exploring the impact of state crackdown on NGOs on subsequent human rights conditions, we look at both de jure measures—or formal legislation that seeks to repress NGOs—as well as the de facto implementation of these measures. This distinction is important—while states may pass anti-NGO laws, these laws can also lie dormant until governments feel the need to enforce them. For instance, Russia passed its 2015 Undesirable Organizations Law with the purpose of targeting and eliminating specific foreign-connected NGOs it deemed dangerous. One of the law’s sponsors, Aleksandr Tarnavsky, described the law as a preventive measure that would not affect the majority of NGOs working in Russia. Rather, the law would be a “weapon hanging on the wall that never fires” and stand as a warning to potentially uncooperative NGOs (Kozenko, 2015).

Simply counting these laws may therefore miss the effect of their de facto implementation. Some governments may even pass laws to create a chilling effect on these organizations. By providing a legal threat, they could compel these organizations to self-censor without even needing to implement these laws in any systematic or meaningful capacity. These laws, especially during moments or crises or contention, “highlight to the wider NGO community-and citizenry-that the government is willing and capable of using the law to repress dissent” (Brechenmacher, 2017, p. 94).

Moreover, the implementation of these laws may not be limited to their legal character. The government may also engage in harassment of NGOs and activists to dissuade NGOs from carrying out their operations. This may include measures such as detentions, short-term incarceration, as well as destruction of valuable property. Finally, counting official laws can also underestimate levels of NGO repression because governments can repress these organizations without relying on formal laws. As prior research in Egypt, Ethiopia, and Russia points out, “rather than systematically enforcing all repressive legal measures-often impossible owing to capacity constraints,” governments may choose to use extra-legal means to intimidate, harass or prosecute a few NGOs or activists (Brechenmacher, 2017, p. 94) These can include arrests, trials, imprisonment, and other violent sanctions against NGO activists such as beatings, threats to families, and attacks on property. As such, de facto crackdown in the form of not just legal harassment but also material and violent sanctions could lead to increases in both physical integrity and civil liberties violations.

Based on these various purposes of NGO restrictions and the different methods states use to implement them, we propose two empirical expectations about the relationship between civil society repression and general human rights:

- Empirical expectation 1 (effect of de jure NGO repression): If a country imposes a formal anti-NGO law, then it is likely to signal future deteriorating human rights conditions.

- Empirical expectation 2 (effect of de facto NGO repression): If a country implements its formal anti-NGO laws and represses civil society, then it is likely to signal future deteriorating human rights conditions.

Data and modeling approach

To test these empirical expectations, we use data on anti-NGO laws, as well as measures from several other larger datasets focused on human rights, political terror, and democratization. Table 1 provides a summary of our key variables.

| Measure | Category | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | |||

| Political Terror Scale (PTS) | Ordered category ranging from 1 (least terror) to 5 (most terror) | Gibney et al. (2019) | |

| Latent human rights values | ≈ −3–5; higher values indicate greater respect for human rights | Fariss et al. (2020) | |

| Predictors | |||

| Total legal barriers | De jure laws | Count of all anti-NGO legal barriers | Chaudhry (2022) |

| Barriers to advocacy | De jure laws | Count of laws restricting NGO advocacy | Chaudhry (2022) |

| Barriers to entry | De jure laws | Count of laws restricting NGO entry, including registration | Chaudhry (2022) |

| Barriers to funding | De jure laws | Count of laws restricting NGO funding sources | Chaudhry (2022) |

| CSO repression | De facto repression | ≈ −3–3; higher values indicate less repression | Coppedge et al. (2020); v2csreprss |

Measuring de jure and de facto civil society repression

To measure de jure repression, we use data on anti-NGO laws from Chaudhry (2022) which includes official NGO laws for all countries (excluding micro-states) between 1990 and 2013. This measure of formal legal barriers does not necessarily represent individual laws. Instead, we count the presence or absence of specific types of anti-NGO legal barriers as a binary variable. If a country passes a law that implements several of these barriers simultaneously (e.g. making registration burdensome and restricting foreign funds), the values for each barrier will flip from 0 to 1. We create indices of the total number of legal barriers in each country based on three broad categories of laws: barriers to entry, funding, and advocacy. We also sum each of these indices to create an overall count of legal barriers.

- Barriers to advocacy (2 possible barriers): (1) NGOs are restricted from engaging in political activities, and (2) advocacy restrictions differ if the NGO receives foreign funding

- Barriers to entry (3 possible barriers): (1) registration is burdensome, (2) NGOs are not allowed to appeal if denied registration, and (3) entry requirements differ if the NGO receives foreign funding

- Barriers to funding (5 possible barriers): (1) NGOs need prior approval to receive foreign funding, (2) NGOs are required to channel foreign funding to state-owned banks, (3) NGOs face additional restrictions if receiving foreign funding, and (4) NGOs are restricted or (5) prohibited from receiving foreign funding

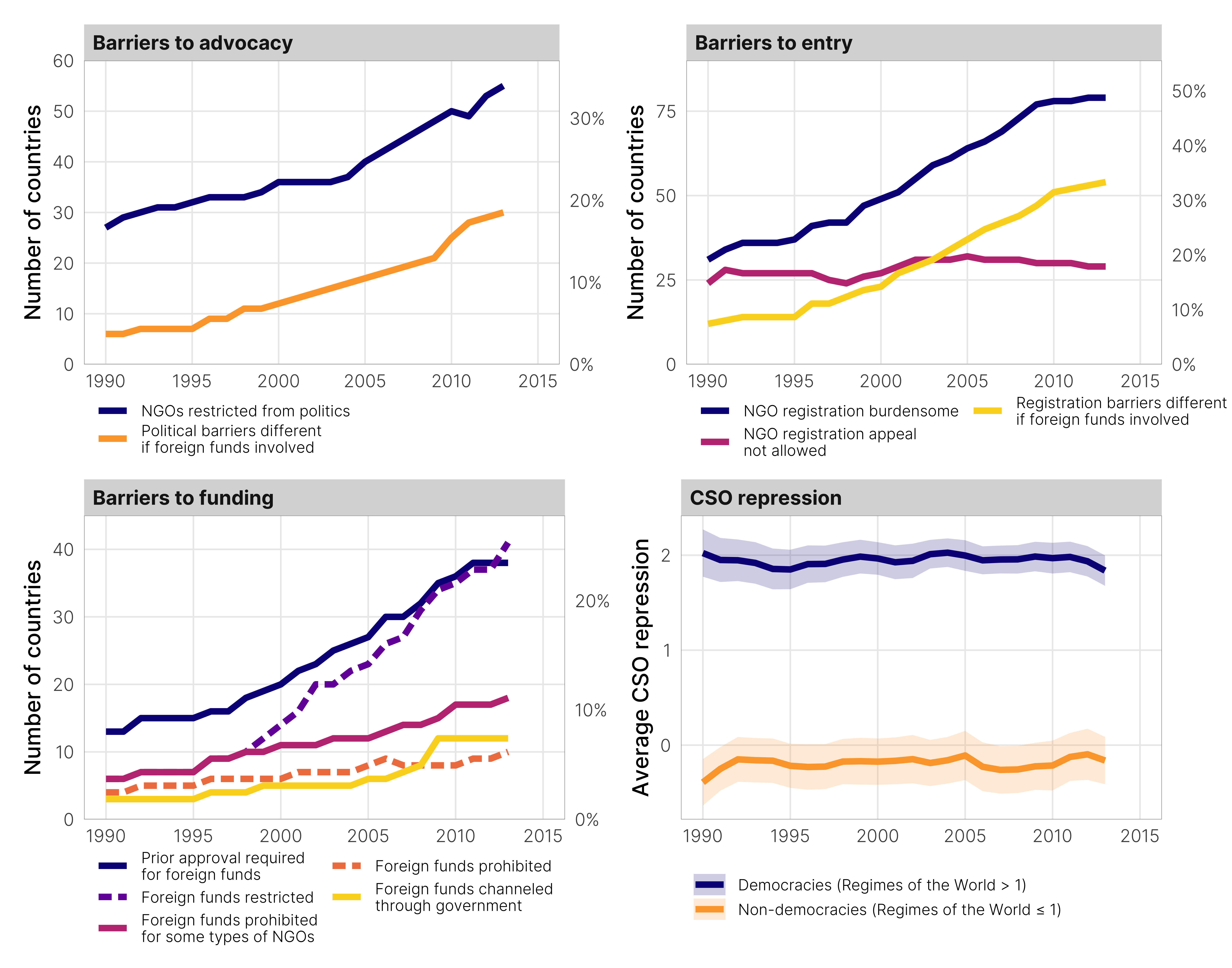

Figure 2: Number of legal barriers to NGO activity per country over time (de jure legislation) and average level of CSO repression across democracies and non-democracies (de facto implementation)

To measure de facto civil society repression in a country, we use the Varieties of Democracy’s (V-Dem) CSO repression indicator (v2csreprss in Coppedge et al. (2020)), which captures the extent to which governments harass, deter, liquidate, and arrest members of civil society organizations. This variable captures repression using an ordinal scale, defining civil society repression as severe, substantial, moderate, weak, or absent. At the most severe levels, the government violently and actively pursues NGOs, seeking to not only deter their activities but also liquidate them. On the least repressive end of the spectrum, NGOs are free to organize, associate, express themselves and criticize the government without fear of government sanctions or harassment. This ordinal scale is then aggregated with a Bayesian item response theory measurement model and converted to a continuous scale that ranges from roughly −3 to 3, with higher values indicating less repression.

Figure 2 shows each of these types of legal barriers per country over time, as well as average levels of de facto civil society repression by regime type. While anti-NGO laws have increased steadily since 1990, there has not necessarily been a corresponding rise in de facto civil society repression, which has remained fairly constant across different regime types. This divergence is likely indicative of the split between de jure laws and their de facto implementation—new legislation is not necessarily implemented immediately and does not always lead to broader NGO repression.

Measuring repression

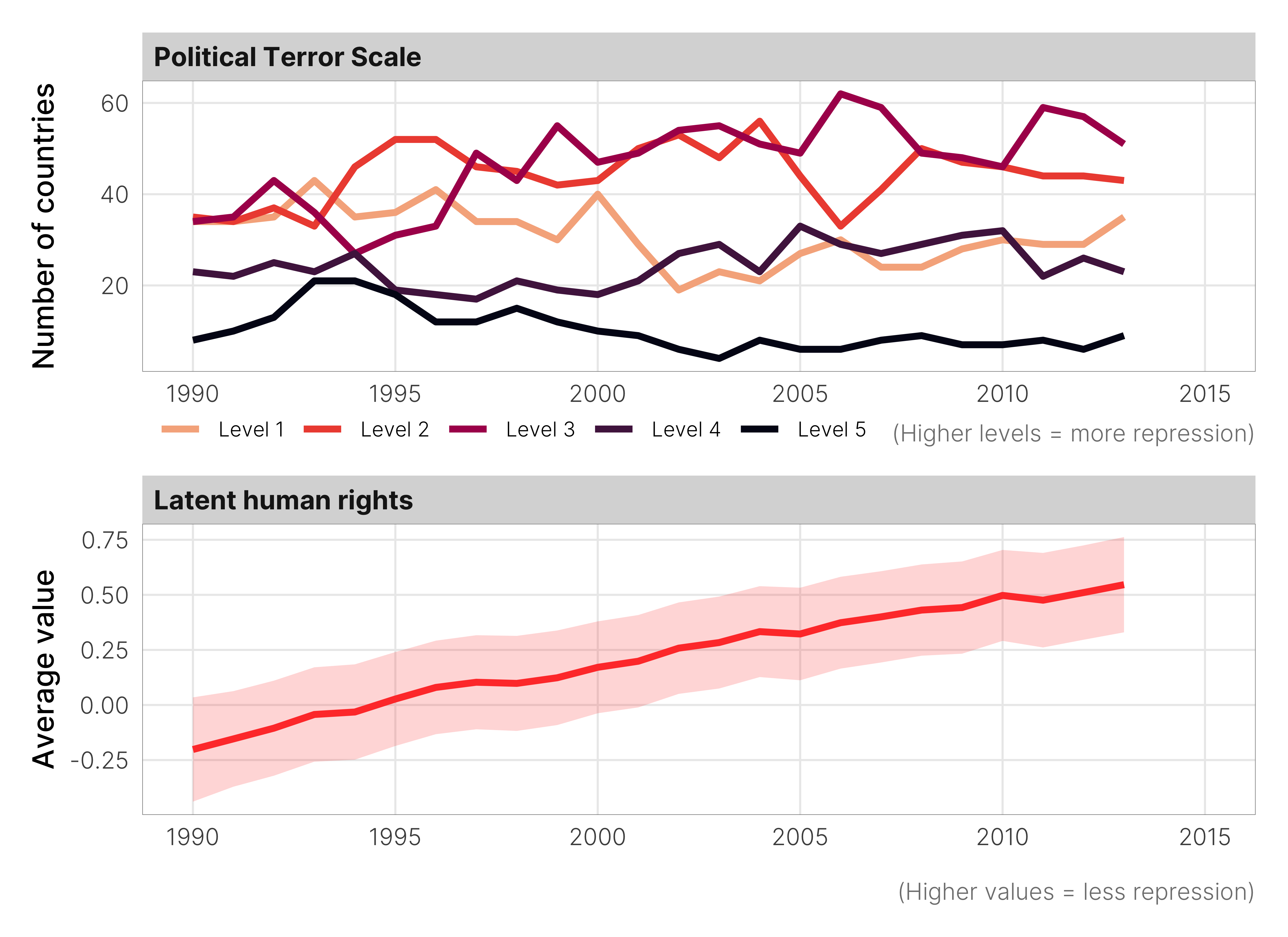

To see how both de jure and de facto civil society restrictions influence general human rights repression, we use two different quantitative measures of repression, each of which capture different dimensions of political and civil violence. First, following Gohdes & Carey (2017), who use the killing of journalists to predict worsening human rights conditions, we use the Political Terror Scale (PTS), which assigns countries to one of five possible levels of repression each year (Gibney et al., 2019), with Level 5 representing widespread political violence—including arrests, imprisonment, political murders, disappearances, and torture. As seen in the top panel of Figure 3, the number of countries at Level 5 has decreased since the 1990s, while most countries are coded as Levels 2 and 3 (moderate levels of political terror).

The five levels of the PTS are helpful for conceptualizing broader trends in human rights abuses. However, these categories are not always granular enough to model or predict a country’s level of political terror. Additionally, the PTS—along with most other measures of human rights abuses—does not account for the systematic changes in the way monitoring agencies have gathered information about human rights violations over time. Accordingly, we use latent human rights scores as an alternative measure of underlying repression (Fariss, 2014; Fariss et al., 2020). This variable is generated from a Bayesian measurement model that incorporates information about human rights abuses from a variety of published repression indices, including the PTS. Because the resulting measure is continuous, it picks up on more minute changes in national-level human rights. Moreover, this variable accounts for changing standards of accountability, which has led to the production of more stringent human rights reports as monitors look harder for abuse, look in more places for abuse, and classify more acts as abuse. When accounting for these changes, the bottom panel of Figure 3 demonstrates the global improvements in average latent human rights values over time.

Figure 3: Key measures of repression over time

Modeling approach

Since we look at whether anti-NGO laws and their implementation can serve as an early warning signal for broader repression, we are primarily interested in predicting repression and not isolating the causal effect of civil society repression on general human rights abuses. We do not include a complete set of covariates to remove confounding relationships, but instead use a more parsimonious set of explanatory variables that strongly predict repression. Following Gohdes & Carey (2017), we control for a country’s level of repression in the previous year (either PTS score or latent human rights value, depending on the model), its level of democracy as measured by V-Dem’s polyarchy index, its logged GDP per capita (measured by the UN), the percent of GDP attributed to trade (measured by the UN), and an indicator for whether the country witnessed more than 25 battle-related deaths (measured by UCDP/PRIO (2020); Gleditsch et al. (2002)). Because changes in the human rights environment take time to be reflected by these larger indices, we model the effect of lagged explanatory variables on repression one year in the future. We also include the lag of civil society laws or repression to account for serial correlation.

We extend Gohdes & Carey (2017)’s previous modeling approach by accounting for country-level variation in repression with multilevel modeling and we include random effects for each country. Accounting for country differences this way results in intraclass correlation coefficients of around 0.7 for each of our three outcome variables, which means that the country-based structure of the data explains more than 70% of the variation in outcome, resulting in model estimates that are arguably more precisely measured. We run multiple models for each of our empirical expectations, based on different combinations of our outcomes and key explanatory variables:

- Expectation 1a: Anti-NGO laws (total; advocacy, entry, funding separately) signal worsening political terror

- Expectation 1b: Anti-NGO laws signal decreasing latent human rights respect

- Expectation 2a: Civil society repression signals worsening political terror

- Expectation 2b: Civil society repression signals decreasing latent human rights respect

We generate predictions with two families of Bayesian regression models. Because the PTS is measured as an ordered category, we use ordered logistic regression to predict future values of the scale. We predict the continuous latent human rights values with Gaussian models. The appendix contains complete details of our modeling approach. We use median values from the models’ posterior distributions as our point estimates and provide credible intervals using the 95% highest posterior density. We declare an effect statistically “significant” if the posterior probability of being different from zero (i.e. above or below) exceeds 0.95.

Results and analysis

We present the results of our models in two stages. First, to see how minor shifts in anti-NGO laws and de facto repression influence future human rights, we examine the marginal effects of our main explanatory variables when all other model covariates are held constant. These effects are by no means causal—rather, they demonstrate how much variation in predicted human rights is possible as the legal environment for civil society improves or deteriorates within a typical country. Second, we present predictive diagnostics for each of our models to examine the improvements in predictions. The results of the ordered logistic regression models can be unwieldy to interpret with plain numbers due to varying intercepts and thresholds between PTS levels. Accordingly, we present graphical results for all our models wherever possible and include complete tables of model results in the appendix (see Tables A2 and A3). For ease in comparing the count of NGO laws with civil society repression, we reverse the x-axis in the marginal effects plots for our second empirical expectation so that increasing the civil society repression represents worse repression rather than less.

Marginal results

How does repression change following increases in NGO laws?

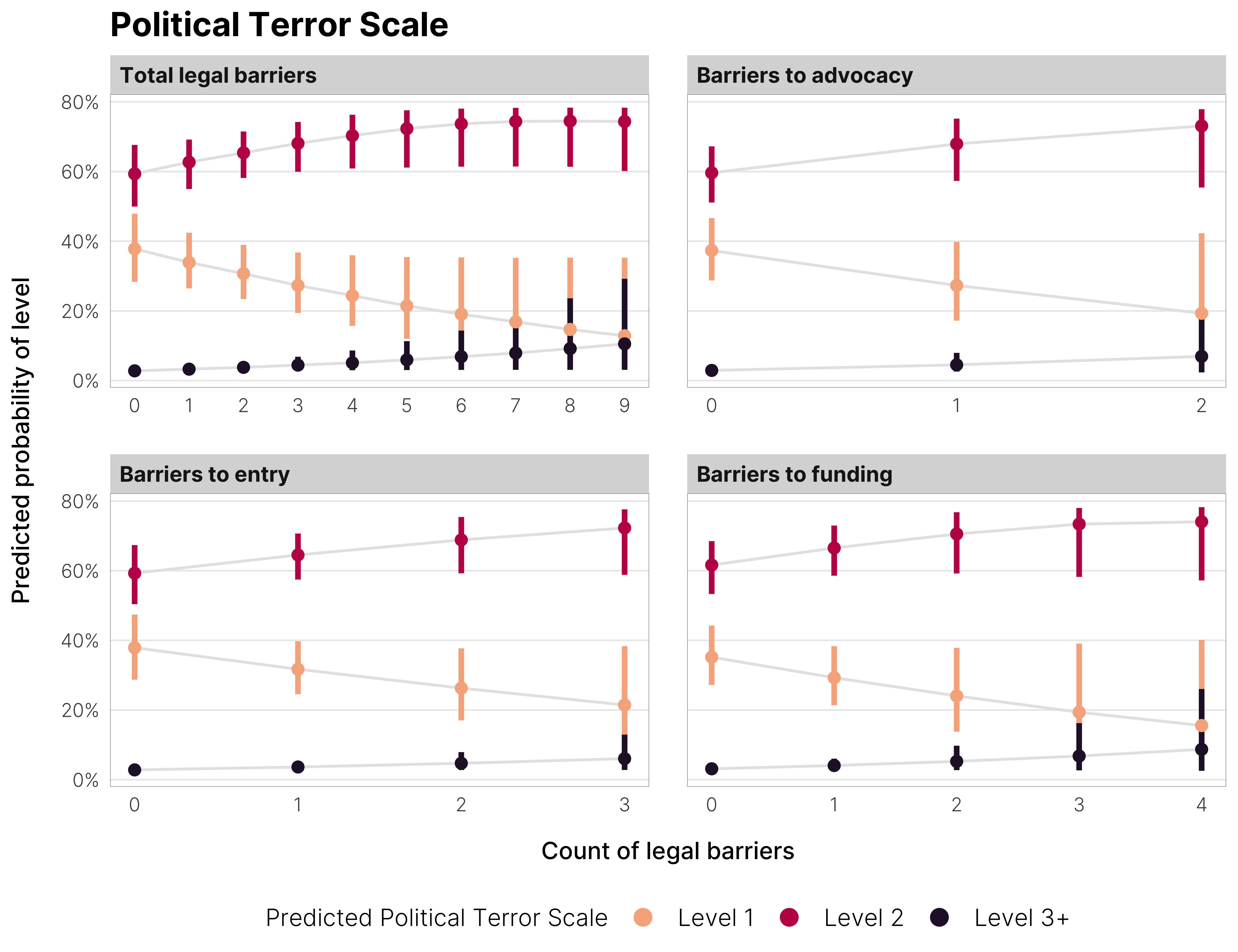

In general, when holding all other covariates constant, the passage of an additional anti-NGO law is generally associated with a higher probability of more severe level of political terror in the following year. The probability of seeing different levels of political terror varies across different possible counts of NGO laws (see Figure 4). In the absence of formal laws, Level 2 of the PTS—an environment where political imprisonment, torture, and beatings are rare—is the most likely category of political terror across all models, appearing a predicted 60% of the time. Level 1, where a country is under secure rule of law, is the second most likely outcome at slightly under 40%. The other categories of the PTS are extremely rare when there are no anti-NGO laws—as such, we collapse them into a single category.

Figure 4: Marginal effects of increasing anti-NGO legal barriers on the probability of specific levels of political terror

As new laws are added, though, the distribution of probabilities for each of the PTS levels shifts. Adding new barriers to advocacy, entry, and funding decreases the likelihood of seeing Level 1 and increases the probability of a country turning to either Level 2 or Level 3 (with extensive political imprisonment and trial-free detention). The marginal effects of all forms of anti-NGO laws results in this turn from Level 1 to Levels 2 or 3+, but this switching effect is strongest following additional barriers to advocacy. Anti-NGO laws do not predict more dramatic shifts in the PTS. Across all counts of anti-NGO laws, the overall probability of seeing Levels 4 and 5 is minuscule, and the passage of additional laws does little to shift that probability. This is not unexpected however—the PTS has a natural ceiling at Level 5. Specifically, in addition to measuring the scope and intensity of government violence, the PTS scale also looks at the proportion of population targeted for abuse. Countries that receive a 4 and 5 are rare, as 4 denotes that murders, disappearances, and torture are a common part of life, while 5 denotes that physical abuses are routinely perpetrated against citizens not involved in politics, and includes cases where governments engage in “scorched earth” counterinsurgency policies or summary executions based on class or ethnic affiliation (Gibney et al., 2019). The majority of movement across PTS categories should thus occur between Levels 1–3.

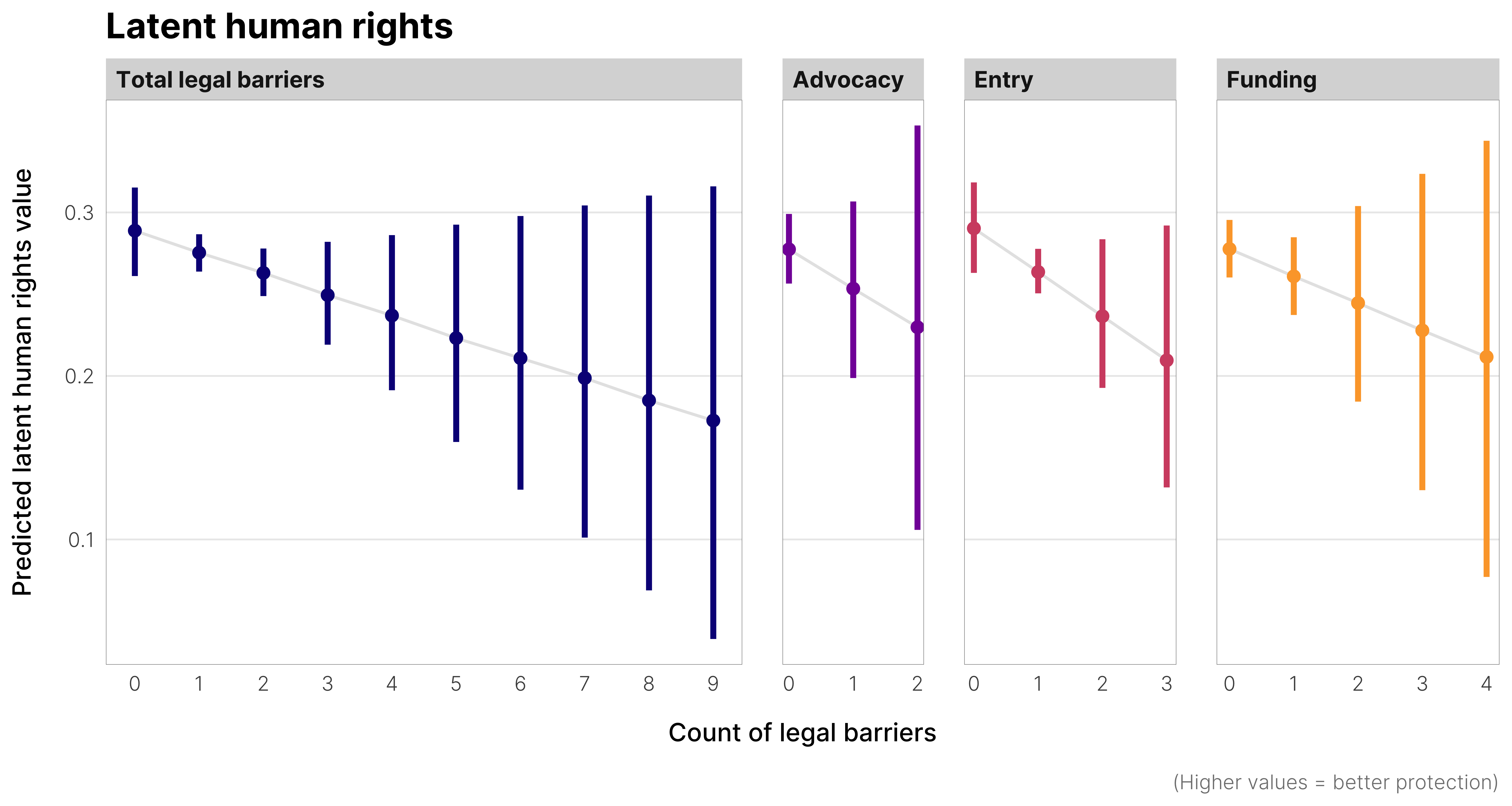

Figure 5 shows the marginal effects of additional anti-NGO laws on latent human rights scores. Across all four models for different categories of legal barriers, holding all other values constant, the predicted level of human rights respect decreases. Adding a new anti-NGO law is associated with a -0.013-point decline in the level of respect for human rights in the following year, on average, representing a roughly 5% decline in predicted the predicted value. The marginal effect is larger (-0.02, or a 9% decline) for additional barriers to advocacy and entry, which represent more burdensome registration requirements than barriers to funding.

At a marginal level, therefore, adding additional anti-NGO laws in countries with low levels of political terror could signal that higher levels of political repression are more likely in the future. Limited repression remains the most likely possible outcome, but the chance of seeing robust rule of law decreases rapidly as more laws are passed, all else equal. This pattern holds when looking at a more continuous measure of human rights protection—countries with a low count of anti-NGO legal barriers tend to have higher predicted values of latent human rights scores, and average protection against abuses decreases as more laws are added.

Figure 5: Marginal effects of increasing anti-NGO legal barriers on latent human rights values

How does general repression change following de facto civil society repression?

The weaker predictive power of formal NGO laws is likely attributable to the fact that de jure NGO legislation may take time to implement—many states need to first establish institutions that oversee the operation and funding of these groups or incorporate threatening NGOs into the regime apparatus (Naı́m, 2007). Further, states that engage in political repression can do so with or without legal justification. De facto civil society repression, on the other hand, represents the actual implementation of anti-NGO strategies—both legal and extralegal—and might be more indicative of future human rights abuses. The results from our second set of models, using V-Dem’s civil society repression index as the key predictor, confirm this.

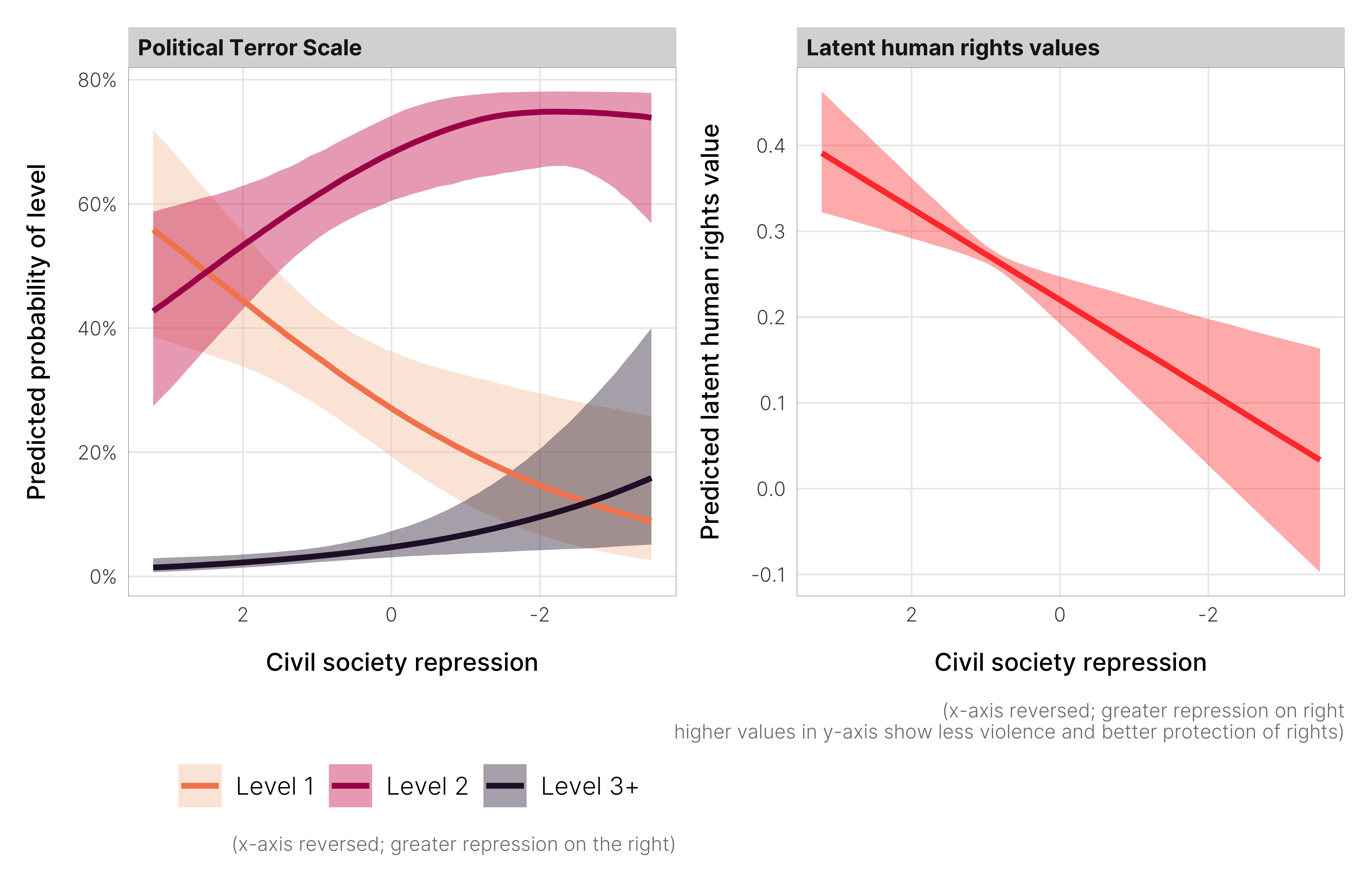

The effect of de facto civil society repression on predicted values of the PTS mirrors what we found previously with our first empirical expectation. As seen in left panel of Figure 6, at the lowest levels of repression, Levels 1 and 2 are the most common predicted outcomes and are each equiprobable at roughly 50%. As de facto CSO repression increases, though, the probability of seeing Level 1 decreases and is replaced with either Level 2 or Level 3. More severe levels of political terror remain exceptionally improbable at any level of preceding civil society repression—we again collapse these into a single category.

Figure 6: Marginal effects of changing levels of civil society repression on the probability of specific levels of political terror and predicted latent human rights values

De facto civil society repression has a noticeable effect on latent human rights values (see the right panel of Figure 6). When holding all other model parameters at their typical values, increased civil society repression predicts a strong decrease in respect for broader human rights: a one unit change in civil society repression is associated with a 0.05-unit change in overall latent human rights. To illustrate the magnitude of this effect, a typical simulated country with a civil society repression index of 0 is predicted to have a latent human rights score of 0.22. This predicted outcome drops to 0.17 with a 1-unit decrease in civil society repression, representing a 24% decline in respect for human rights in the following year.

When holding all other factors equal, the de facto implementation of anti-NGO laws thus appear to be a stronger marginal indicator of future repression than simply the passage of these laws. While these laws may be intended to have a chilling effect on civil society (and certainly have a chilling effect on levels of aid and NGO operations as shown by recent literature), these de jure laws by themselves do not have similar adverse consequences on respect for physical integrity rights and civil liberties. In countries with low levels of political terror, it can potentially serve as a weak signal of a more general increase in political violence in the future, but predict more substantial changes in general respect for human rights. The difference in the effects of laws vs. their de facto implementation could also potentially be explained by the time frame of these strategies. As we explore in the next section, de jure civil society laws are a long-term strategy to prevent threats to the regime from coalescing in the first place. As such, the effects of these laws in terms of their predictive power may require a much longer time period under study. In contrast, de facto crackdown on NGOs may signal that a state needs to react sooner due to the immediacy of the threat.

Predictions

These predicted probabilities and outcomes are conditional on all other model parameters being held at their average values and show the effect of hypothetically changing a single predictor to different values. They do not show how well these models work with actual data. Following Ward & Beger (2017) and Gohdes & Carey (2017), we test the predictive power of both sets of our models using out-of-sample prediction. We divide our complete data into a training set and a test set—the training set includes data from all countries from 1990–2010, and the test set includes the last three years of data (2011–2013). We re-run each of our models using our training data and then use the estimated parameters to predict political terror, physical violence, and private civil liberties for the test data. Additionally, we estimate a model for each outcome without predictor variables for civil society laws or repression as a baseline measure of model performance.

| Prediction | Baseline | Total legal barriers included | Barriers to advocacy included | Barriers to entry included | Barriers to funding included | Civil society repression included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wrong | 109 | 107 | 110 | 108 | 108 | 111 |

| Correct | 376 | 378 | 375 | 377 | 376 | 374 |

We assess predictive power in a few different ways, depending on the model used to predict the outcome. For the ordinal PTS, Table 2 shows a count of correct and incorrect predictions from each model. We measure the predicted accuracy of our latent human rights models with the root mean squared error, provided in Table 3. In the appendix we include lists of country-year cases that see improved predictions when taking civil society laws and repression into account.

Including civil society restrictions—both de jure and de facto—does very little to improve predictions of political terror. As seen in Table 2, no model provides more correct predictions than the baseline model, and some models perform worse. Accounting for anti-NGO activities does improve predictions in eight cases (see Table A1 in the appendix), but it also results in an equal number of incorrect predictions.

| Latent human rights values | RMSE | % change from baseline |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline model | 0.1862 | — |

| De jure repression | ||

| Total legal barriers | 0.1872 | 0.54% |

| Barriers to advocacy | 0.1872 | 0.53% |

| Barriers to entry | 0.1863 | 0.03% |

| Barriers to funding | 0.1880 | 0.95% |

| De facto repression | ||

| Civil society repression | 0.1857 | -0.27% |

When looking at the overall latent human rights values in a country, including de jure and de facto repression does very little to improve predictive accuracy. As Table 3 shows, accounting for de facto civil society repression only reduces the RMSE by 0.27% compared to the baseline, while accounting for de jure laws worsen the models’ predictive power slightly. While these gains in predictive power appear negligible, they are somewhat comparable with the findings of previous work. For instance, in their work on the effect of the murder of journalists on predicting future political terror, Gohdes & Carey (2017) find that accounting for violence against the media adds five correctly predicted cases of PTS scores and improves predictions in seven cases.

We thus again find that de facto civil society repression is a stronger predictor of worsening human rights in the future than formal laws on their own. Actual government interference in civil society act as a possible signal of future abuses of civil and human rights better than simply the presence of a law that could potentially be used at some point in the future.

Discretionary disconnect between de jure and de facto NGO repression: The case of Egypt

When looking at both marginal effects and improvements in predictive power, we find that the de facto implementation of anti-civil society measures are a stronger indicator of future repression than de jure anti-NGO laws. One reason for this disconnect between law and implementation is that laws targeted at NGOs are often not designed to be used immediately, but instead serve to protect regimes against potential threats in the future. Egypt provides a prime example of this mechanism.

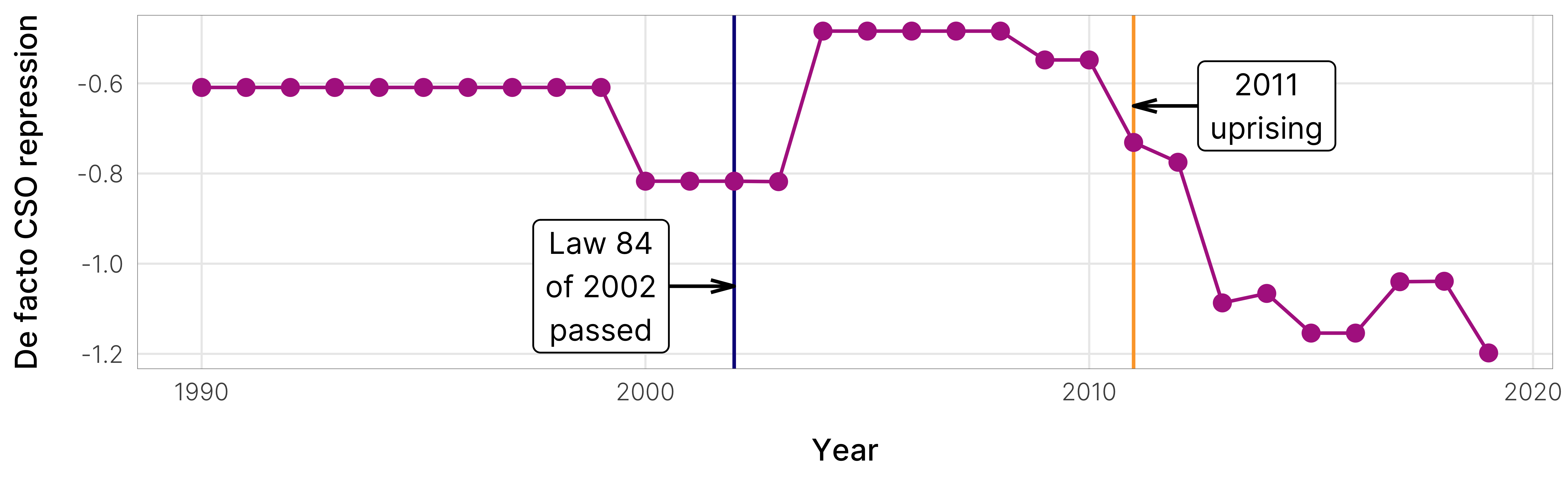

Figure 7: The disconnect between Egypt’s de jure 2002 law and the widespread de facto repression of civil society a decade later

In the wake of domestic terrorist attacks in the late 1990s, the Egyptian parliament passed Law 84 of 2002, or the Law on Associations and Foundations (Agati, 2007, p. 60). The new law imposed specific limits on international and foreign-connected NGOs and required that all NGOs register with the Ministry of Social Solidarity. Any revenue from foreign associations to nonprofit organizations working in Egypt required both recipients and donors to submit multiple applications to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and state security, and the latter maintained ultimate veto power over the approval process (Thabet, 2004, p. 162).

Though it granted the government substantial oversight power over NGOs, Law 84 also allowed for enormous discretion in enforcement. In spite of the strict legal framework, the Egyptian NGO sector nearly doubled in size between 1993–2011 (Brechenmacher, 2017), largely because of the government’s selective and targeted enforcement of the law. When NGOs became too contentious or posed a threat to the regime, officials could use minor infractions in more obscure parts of the law to fine or shut down the organization, but these attacks on NGOs were limited to specific NGOs. As seen in Figure 7, Egypt saw its highest, most stable, and most open level of broader civil society repression in the decade following the passage of Law 84.

The calculus of enforcement changed as the state faced increased threats to its stability. Following Hosni Mubarak’s removal as president in February 2011, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) took temporary control over governing the country. SCAF worked throughout the year to curtail protests and often resorted to violence to break up demonstrations, which then led to larger and more violent protests in response. The tension culminated on December 16, when troops filled Tahrir Square to put down an anti-SCAF demonstration, killing 10 and wounding more than 400. Two weeks later, Egyptian security forces raided the offices of 17 local and international NGOs—including Freedom House, the National Democratic Institute, and the International Republican Institute—and arrested dozens of domestic and international NGO staff (Fadel & Warrick, 2011). The stated legal pretext for this raid was that the organizations were not officially registered and thus in violation of Law 84. The de jure law—constantly looming in the background, but enforced selectively—was finally implemented and enforced more expansively. In the years after the 2011 uprising, post-revolutionary regimes have enforced the law more consistently, further constricting the space for civil society (Ruffner, 2015), as seen in the rapid drop in broader civil society repression in Figure 7.

Law 84 (and its replacement Law 70 of 2017) is thus a useful lever for selectively controlling the allowable space for dissidence and leaving open the possibility of future human rights abuses. The law’s built-in discretionary authority permits the government to give the appearance of concessions and openness to civil society while simultaneously providing the government with the ability to target individual NGOs and the right to engage in broader crackdowns of associational rights.

This trend holds across many other countries as well. For instance, even though India passed an anti-NGO law (containing multiple barriers to funding and advocacy) in 1976, it has not always been uniformly implemented. Rather, having an anti-NGO law on the books serves the state’s long-term strategic interests, enabling it to crack down on NGOs when they start posing electoral or economic threats to the state (Chaudhry, 2022). Anti-NGO laws can therefore serve as a useful avenue for future human rights abuses, sometimes with years separating the official passage of the law and the large-scale implementation of the law, explaining why de facto levels of NGO repression serve as a stronger predictor of worsening respect for human rights abuses.

Conclusion and implications

Strengthening civil society is an important precondition for democratic transition and consolidation. This article shows dramatic growth in de jure regulations constraining NGOs; laws that can lay the foundation for subsequent de facto repression of civil society. Given these potential knock-on effects, in this paper, we posited that the ongoing global crackdown on NGOs could predict worsening human rights abuses. Using original data on de jure and de facto NGO repression from 1990–2013, we find weak support for the predictive power of de jure restriction on political terror and overall latent human rights values. Marginal predictions show that—all else held equal—adding new anti-NGO laws increases the probability of seeing moderate levels of political terror and is associated with worsening human rights conditions more generally. However, in contrast to de jure laws, de facto levels of NGO repression—including both legal and extra-legal means of crackdown—tend to increase the probability of more moderate political terror. Additionally, this repression is associated with worsening respect for broader human rights in the future.

Importantly, the weak predictive power of anti-NGO laws by themselves reflects the purpose of NGO restrictions. Encroachments on private civil liberties such as restricting freedom of association and funding are not nearly as violent as events like physical integrity rights violations and political terror. Anti-NGO laws could possibly be a side effect of authoritarian stability-seeking behavior, similar to election tampering, media censorship, cronyism, and rent-seeking, rather than an overt signal of impending serious human rights abuses. The global shrinking of civic space or increasing passage of anti-NGO laws is thus not likely an early warning sign for future violent repression—states typically signal their future repressive intentions with more violent methods, such as the persecution and murder of civil society activists and the media. Instead, civil society is a possible “canary in the coal mine” for impending violations of other civil rights, such as the freedom of religion, labor rights, property rights, and the freedom of movement.

However, it is also important to state that while anti-NGO laws do not seem to be a predictor of broader human rights repression over the period under study, it does not imply they are not having a chilling effect on NGO operations. The broader literature on state repression of NGOs has shown that de jure laws can have numerous adverse consequences. Foreign funding laws have led to a 32% decline in bilateral aid flows (Dupuy & Prakash, 2018). NGOs that are underfunded and understaffed tend to shut down when faced with increasing restrictions (Heiss, 2019). In sum, while de jure laws do not effect levels of physical integrity and civil liberties violations in particular, research has found that they do have other adverse consequences. Moreover, since the actual implementation of these laws through de facto civl society repression can have negative effects on broader patterns of human rights abuses, the passage of these laws may still be a concerning first step that paves the path for future implementation.

The dramatic growth in these laws has important implications for the power of the human rights regime and international human rights law. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Association has pointed out that the right of NGOs to seek, receive and utilize resources is an essential component of the right to association (Kiai, 2013). Anti-NGO laws, including barriers to funding, violate core human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). In contrast to the influential work on the impact of transnational advocacy networks and international law, which places immense value on the ability of civil society groups to monitor, shame and reform state behavior, the results in this article show that reforms resulting from international legal pressure and mobilization may be short-lived. Rather, states may be learning to counter these dynamics by ramping up repression.

References

Following CIVICUS, open civic space in a country indicates that the state enables and safeguards citizens’ freedom to form associations, authorities are tolerant of criticism from CSOs, and that laws governing freedom of peaceful assembly adhere to international laws and standards.↩︎

In this article, we use the terms “anti-NGO laws” and “de jure NGO laws” and “NGO restrictions” interchangeably.↩︎